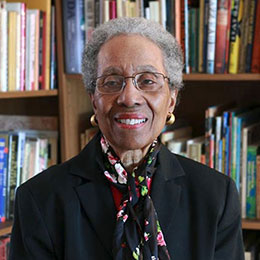

In this season of gift-giving we want to look at the gift of poetry, specifically the poetry and writing of Eloise Greenfield. Since publishing her first poem in 1962, she has written more than forty-five books for children and was the recipient of the 2018 Coretta Scott King Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement. Her books consistently win awards, including the 2012 Coretta Scott King Award for The Great Migration Journey to the North. We want to dip into her work and share the books we have located so far. Studying Eloise Greenfield is an on-going project for us, and we hope to inspire you to take on this project too.

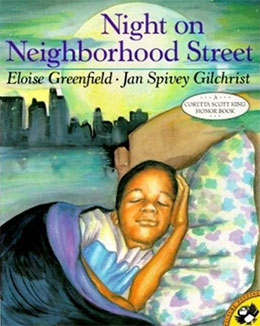

Night on Neighborhood Street (1991) was one of our early encounters with Eloise Greenfield. The format allows Greenfield to give us a community in this series of poems about people who live on one street. No story arc. No problem encountered and solved. Glimpses of lives in one neighborhood on one night.

Night on Neighborhood Street (1991) was one of our early encounters with Eloise Greenfield. The format allows Greenfield to give us a community in this series of poems about people who live on one street. No story arc. No problem encountered and solved. Glimpses of lives in one neighborhood on one night.

The first poem in a kind of establishing shot. It’s evening, now, of a day that began when “morning mama and daddies/roused the children/ with soft sugar-names/and the scent of hot buttered/bread.” Children play singing games on the sidewalk—We’re goin’ around the mountain two by two, Rise, Sally Rise–as night falls on Neighborhood Street. From that opening we get the glimpses of individual lives.

The glimpses are wonderful. In “Buddy’s Dream” Buddy dreams himself a double and they dance together. “Go Buddy Buddy/Go Buddy go.” Then he dreams two more of himself — an abundance of exuberance. But it’s not all exuberance. In “Little Boy Blues” we read “He’s got the little boy blues. /He’s all alone/Waiting for his best, best friend to come home…He’s got more lonesome than he can use. /He’s got the bad, bad, long-faced hurt/ and little boy blues.” On the facing page we see a boy and his dad playing a game. We hope it’s the same boy.

Neighborhood Street is not all games either. There is “The Seller,” “carrying his many packages of death.” But there is love and hope. In “Nerissa” a little girl’s mama is sick, her daddy’s out of work, and although she wants to help “she can’t bring dinner/like the neighbors do/she can’t mend the hole/in her daddy’s shoe/but she’s a big help/ when she tickles her folks/by telling them the best old/bedtime jokes.” In another poem Tonya has friends come for an overnight her mother tells them she loves them all and she plays her trumpet for them. Tonya’s mother plays once again when the children are sleeping — a tune to caress all the kids on Neighborhood Street.

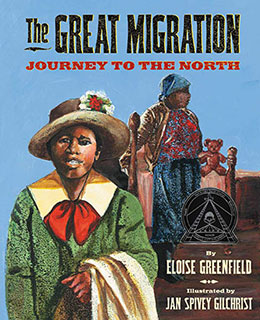

Neighborhood Street seems to be part of an urban environment. In The Great Migration Journey to the North (2011), also illustrated by Jan Spivey Gilchrest, we see individuals and families on their way to the city.

Neighborhood Street seems to be part of an urban environment. In The Great Migration Journey to the North (2011), also illustrated by Jan Spivey Gilchrest, we see individuals and families on their way to the city.

This book begins with an author’s note to give readers a context for the poems. “Between 1915 and 1930 more than a million African Americans left their homes in the South, the southern part of the United States, and moved to the North. This movement was named the Great Migration.” She reminds people that African Americans were not safe in the south, could not find jobs, chafed under Jim Crow restrictions. She relates that her own family was part of this migration. Her father went north when Greenfield was three months old. The family followed a few months later. The poems have a chronological order. First “The News.” “They read about it, heard/about it, in letters and newspapers/sent down from the North, /from visiting cousins and brothers/and aunts…” Then “Goodbyes” from a Man saying goodbye to the land; a girl and boy; a woman, who says, “I can’t wait to get away/I never want to see this town/again….” And a very young woman who is leaving her mother behind.

These goodbyes are followed by sections called “The Trip,” “Question,” (“Will I make a good life/for my family, /for myself?”); “Up North.” Greenfield ends with more details of her own family’s story. “We were one family/among the many thousands. /Mama and Daddy leaving home, / coming to the city,/with their/hopes and their courage,/their dreams and their children,/to make a better life.”

Jan Spivey Gilchrist’s art captures the yearning, the determination, the fear of people as they make the decision to migrate. Faces from individual stories show up later in the train cars headed north. The voices in these poems bring us close to the heartbreak of leaving home, leaving family, and the courage of striking out for a better life.

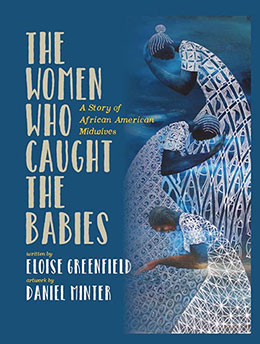

There is courage and there is joy in The Women Who Caught the Babies (illustrated by Daniel Minter, 2019). This is a beautiful book about African American midwives. A note from the author at the beginning of the book gives readers a quick history of African American midwifery, “With this book I want to take you back only as far as the Africa of a few hundred years ago. That’s when millions of Africans were forced from their homelands, brought to American and enslaved. Some of the enslaved were midwives…women (and some men) who help bring babies into the world. Midwives use the word ‘catch’ to describe what they do. They say they ‘catch’ the babies as they are being born.” Then we get the poems. First the searing poem about midwifery during the time of slavery. “…The women, also kidnapped, /also shackled, /made the torturous voyages/across the ocean into slavery./In America, African girls/on the brink of womanhood,/watched the women and learned,/then took their turns/at catching the babies,/and so, too, the next generation,/and the next, and the next,/and the next.”

There is courage and there is joy in The Women Who Caught the Babies (illustrated by Daniel Minter, 2019). This is a beautiful book about African American midwives. A note from the author at the beginning of the book gives readers a quick history of African American midwifery, “With this book I want to take you back only as far as the Africa of a few hundred years ago. That’s when millions of Africans were forced from their homelands, brought to American and enslaved. Some of the enslaved were midwives…women (and some men) who help bring babies into the world. Midwives use the word ‘catch’ to describe what they do. They say they ‘catch’ the babies as they are being born.” Then we get the poems. First the searing poem about midwifery during the time of slavery. “…The women, also kidnapped, /also shackled, /made the torturous voyages/across the ocean into slavery./In America, African girls/on the brink of womanhood,/watched the women and learned,/then took their turns/at catching the babies,/and so, too, the next generation,/and the next, and the next,/and the next.”

Additional poems show us midwives “After Emancipation,” in the early 1900s, and the early 2000s. The book ends with “Miss Rovenia Mayo,” the midwife who caught Eloise Greenfield. “On the evening of May 17, 1929, /Miss Rovenia Mayo caught me, Eloise.”

This, too, is a story of community, of people sharing the joy of new life and taking care of each other. With stunning art and powerful text, this book honors the midwives, the women who “caught the babies, /and catch them still/ welcome into the world/for loving.”

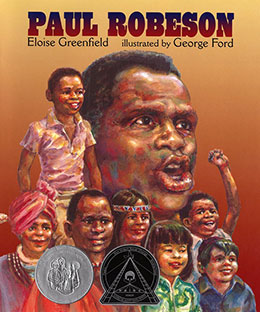

We cannot end without mentioning Greenfield’s moving biography of a giant of the 20th century. Paul Robeson (1975) illustrated by George Ford, and updated and released in paperback in 2009, this book is as important as it was 45 years ago. It tells the story of a brilliant artist and courageous man who would not bow to our country’s anti-Communist hysteria of the 1940s and ‘50s.

We cannot end without mentioning Greenfield’s moving biography of a giant of the 20th century. Paul Robeson (1975) illustrated by George Ford, and updated and released in paperback in 2009, this book is as important as it was 45 years ago. It tells the story of a brilliant artist and courageous man who would not bow to our country’s anti-Communist hysteria of the 1940s and ‘50s.

Paul Robeson was the son of a man who escaped slavery and moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where he was minister of a church. At Rutgers he was an All-American football player. He received a law degree from Columbia University, but Robeson could not find a job. He was also a brilliant singer and actor and that became his career.

Paul Robeson could not help but speak out against the many injustices perpetrated on African Americans in this country. He visited Russia and felt life was better for people of color over there. He had Communist friends. Rabid anti-Communists led by Joseph McCarthy, accused him of being a Communist. He was blackballed. “Owners of theaters, concert halls, and radio and television stations would not allow him to sing or act. Store owners stopped selling his recordings. Some of them were angry with him, and some were afraid that they would be punished too.”

When he did sing, those who came to see him were sometimes attacked by Robeson’s enemies. He was denied the right to travel to other countries. “Several times he sang at the line between the United States and Canada. He stood on a stage in the United States, on one side of the line. His audience sat in a park in Canada, on the other side of the line.” His story reminds us how music can cross borders even when people aren’t allowed to. Robeson is a genuine hero of our country and we are grateful to Eloise Greenfield for sharing his story with children.

In this film clip on YouTube, you’ll be able to watch Robeson singing “Joe Hill” for Scottish miners, which just might bring tears to your eyes. In another film clip Robeson, who is forbidden to leave the United States, sings for Welsh miners over transatlantic telephone.

This too brief look at Eloise Greenfield’s work shows a writer intent on portraying community, shared responsibility, joy, and courage. Her agent, Catherine Balkin writes on the Balkin Buddies website that Eloise Greenfield “says her mission is twofold: (1) to contribute to the development of a large body of African American literature for children and (2) to continue to fill her life with the joy of creating with words.” Mission success! Thank you for so many gifts, Eloise Greenfield. Your words bring us joy and courage — and awe.

A few other titles among Greenfield’s many wonderful works:

Africa Dream illustrated by Carole Byard

In the Land of Words illustrated by Jane Spivey Gilchrist

Honey, I Love illustrated by Jane Spivey Gilchrist

She Come Bringing Me that Little Baby Girl illustrated by John Steptoe

Thank you so much for the background about her and introducing me to so many of her books!

I fell in love with her when I first read HONEY I LOVE AND OTHER LOVE POEMS (llustrated by Diane and Leo Dillon).

Oh, my. I think was in high school. I swooned. It still has a starring role in my bookshelf.