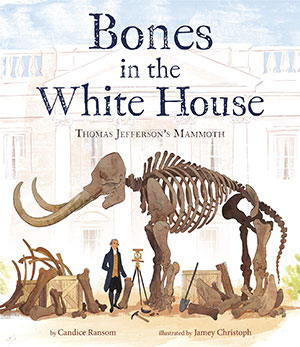

On my “final” draft of Bones in the White House: Thomas Jefferson’s Mammoth, I drew a line of little mastodons trooping across the bottom of the manuscript pages. Each animal bore a date that matched a sidebar fact or referenced the main text. I thought this was a clever way to remind readers of the march of time.

On my “final” draft of Bones in the White House: Thomas Jefferson’s Mammoth, I drew a line of little mastodons trooping across the bottom of the manuscript pages. Each animal bore a date that matched a sidebar fact or referenced the main text. I thought this was a clever way to remind readers of the march of time.

The first little mastodon (or “mammoth,” as the creature was called in Jefferson’s day) was labeled “700 million years ago,” the second “13,000 years ago,” the third “11,000 years ago,” inching along like an Ice Age glacier to the time period of the story. I did not include the mastodon timeline on manuscript I submitted to my agent, but the sidebars remained. How else would kids know that the shell Jefferson found on a Blue Ridge mountaintop had once been covered by an ancient ocean? Or that huge mastodons roamed North America, only to disappear a mere 2,000 years later?

“Revise,” said my agent, meaning keep my story focused and simple. With a sigh I banished the mastodon parade and axed the sidebars. How would I convey to readers that my book was as much about history as it was about the science of discovering a new animal in the New World, and vice versa? With the emphasis on STEM in today’s classrooms, I worry that students won’t see the entire picture, won’t know that scientific advances are based in history.

When I began researching Bones, working backwards from one sentence in a nonfiction book that stated Thomas Jefferson unpacked three crates of fossils in the East Room of the White House, I was keen on the science aspect. What kind of fossils? Where did they come from? Soon, however, I found myself grabbing every history book I could find to learn more about how science was perceived in the late eighteenth century. It was new! It was tangled up with religion! It was being sorted out by brave and curious people!

I loved reading about natural philosophers (the term “scientist” was not yet coined) working in France, Germany, Great Britain, North and South America so much that when my book was finished, acquired, and at the presses, I kept on reading. I’m still reading. It’s a huge picture and I want to see all of it.

Much has been made of the viral video, “TikTok Math Girl,” who asked how we know if math is real and why do we need it. Her question was defended by various experts and answered in depth by mathematician Eugenia Cheng. I asked my husband, who has a degree in mathematics, if he studied Euclid’s life or Thales of Miletus? He said they didn’t have much time to go into math history as they had to concentrate on practical applications.

Not much has changed. Students today know Einstein as a twentieth-century figure famous for his theory, but on whose shoulders did Einstein stand? (Copernicus, Newton, Michael Faraday, among others.) Einstein’s e = mc2 didn’t spring from his forehead but was developed from his studies and his background. These facts lend context and perspective to his achievements, and show budding physicists that it took years — and some missteps — to develop his theory.

Not much has changed. Students today know Einstein as a twentieth-century figure famous for his theory, but on whose shoulders did Einstein stand? (Copernicus, Newton, Michael Faraday, among others.) Einstein’s e = mc2 didn’t spring from his forehead but was developed from his studies and his background. These facts lend context and perspective to his achievements, and show budding physicists that it took years — and some missteps — to develop his theory.

I included four pages of back matter with my final manuscript. Only two were used, due to space constraints. I so wanted readers to know where the dinosaur discoveries were at the time of my story. And how the continents formed and changed. And how Darwin set people straight — and the world on its ear — with his theory of evolution, all part of the whole picture of which my story is just a small part. But maybe that picture is too big for one children’s book. I can always write another.