Reading and admiring the books of Paul O. Zelinsky raises my curiosity. How does he work on the illustrations for his own books and those of other authors? What is he thinking about when he evolves his unforgettable characters?

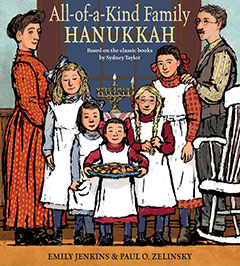

Of his newest book, All-of-a-Kind Family Hanukkah (written by Emily Jenkins), Mr. Zelinsky says, “Now that I’m done, when I consider how I worked on these pictures, trying to rough them up when they got too smooth, to flatten them out when they got too round, to maintain a sense of texture throughout, I think that perhaps what I was really trying do was represent the qualities of a good potato latke! Take a look at one, very close up, and see if you agree.”

A potato latke? This makes me curious …

What is the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

I pull off a sheet from my note pad and write down a list of the things I want to get done that day. I then promptly lose that note under other pieces of paper on my drawing table.

How long do you think about a new book before you start working with it on paper?

It’s hard to define when I start working on something on paper. At any point after I’ve gotten a manuscript, on the edges of other pages: meeting notes, or shopping lists, or anything else, little sketches may appear that relate to it. The earliest stages aren’t work, anyway; they’re play, or it just won’t work.

Also, I may be sort-of thinking about a next book before I’m done with a current one, in which case I won’t do much beyond this casual, unplanned sketching (and stuffing the sketches into a folder if they seem worth saving); and the amount of time I spend at this depends on how soon I finish the current book.

But if the question is how quickly does a book progress from just-read manuscript to serious sketches to finished art, the answer is: I don’t think there’s any way to know.

What is the quality of the light in your studio? Where does the light come from?

My studio faces as close to north as possible, as studios are supposed to do. That’s so sun doesn’t move across the room as the day goes by, radically changing the light conditions. The window light includes some light from the sky, and the rest reflected off the grass and walls of a beautiful churchyard across the street. So the overall light coming in my windows usually has a greenish cast. I also have some fluorescent light fixtures, thin bright tubes that emit a surprisingly decent color of light compared to the fluorescents of the past. Clipped to a bookcase I have two bright LED lamps that I bought to match the lighting used in the American Writers Museum in Chicago—I was working on a mural for them, and it was important to know how things would look in their real home. (The mural was finished just in time for the museum’s opening, in May of 2017).

How do you organize your tasks? Does that differ from book to book?

I try to organize my tasks, but I would not call them, in the end, organized. Some procedures have evolved that I do use regularly, such as my system for hanging finished art on my wall (if the art isn’t digital). I have sticks of square wooden molding hanging from the picture molding on my walls, with pegs sticking forward at intervals of about 15 inches. I can vary the space between sticks to match the width of the art (which I attach to cardboard with holes for the pegs), and it’s all quite flexible and reusable.

What does your work day look like?

No pattern that I can see. The closer to the deadline, the more efficiently I work, except for sometimes. On Thursday mornings if at all possible I go to the Minerva’s Drawing Studio—that’s the name of a figure drawing workshop/studio on New York’s Lower East Side, not far from me, where on Thursdays its founder Minerva Durham talks about drawing, art, history, philosophy, and more, in a wonderfully idiosyncratic way, during the model’s breaks. I think that drawing the figure keeps my hand-eye coordination from falling away—the human body is probably the most demanding thing you can draw. And I’m fascinated by anatomy.

What’s your favorite paper to use for creating art?

It’s been a while since I used it, but for watercolor I have been most comfortable with Arches cold press paper. For a combination of watercolor and digital printing, a technique I’ve used on a few books, I have a stash of Whatman 90 lb. hot press, an amazing paper that, naturally, went out of production over ten years ago. For digital printing I like Moab Entrada Rag Bright, but you really can’t touch it up manually, which is too bad.

What is the most reliable of the tools you use to create art?

My computer is most reliable in the sense that mistakes are infinitely forgivable. Otherwise, I don’t really know. Oils work well for me; watercolor is riskier, and other mediums have their own difficulties.

The Horn Book asked me to write about this once, and what I wrote still applies except for the part about the computer, which has changed one hundred percent.

How do you save the thoughts you don’t have time to execute that day?

I write them down on little pieces of paper that I promptly lose. I also write them in my phone’s Notes app and lose them there. When the time comes to execute these ideas, I do find that most of them (as far as I know) come back to me; I actually don’t mind this process.

Do you work on more than one book at a time?

Every time I’ve tried to work on more than one book at a time, I find myself working on one book at a time. At most.

Paul O. Zelinsky will receive a 2018 Eric Carle Honors Artist award for lifelong innovation in the field. The Honors will be bestowed on Thursday, September 27, 2018, at Gaustavino’s in New York City.

Do spend some time on Paul O. Zelinsky’s website. There are many opportunities to be fascinated tucked here and there.