Working on my magical realism middle-grade novel, I realized I couldn’t visualize where my story is located. I could describe immediate buildings, but the landscape was blank. If I couldn’t see it, neither could a reader. As often happens when writing a novel, the universe sends what you need. It sent me George R. Stewart’s 1944 book, Names on the Land, which begins:

Once, from the eastern ocean to western ocean, the land stretched away without names. Nameless headlands split the surf; nameless lakes reflected nameless mountains… Men came at last, tribe following tribe, speaking different languages and thinking different thoughts. According to their ways of speech and thought they gave names, and in their generations laid their bones by the streams and hills they had named.

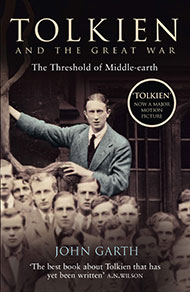

Names! My worn Virginia atlas usually serves for inspiration, but this project demands original topography and names. I re-read The Hobbit, a treasure trove of place names, pairing it with John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War. Tolkien’s experiences in World War I influenced his creation of Middle-earth.

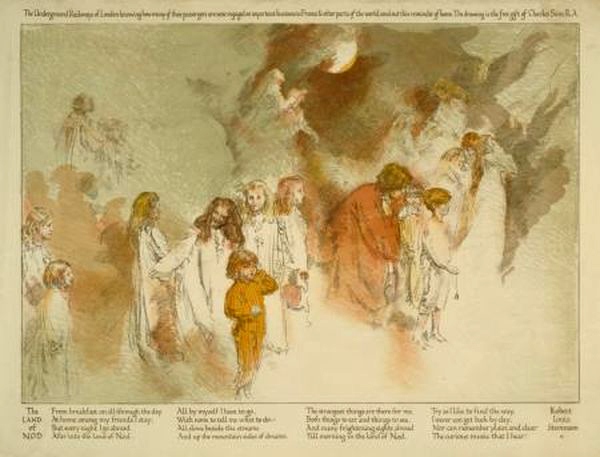

Tolkien was fresh from Oxford when he entered the service in 1915. He’d already begun inventing languages and scribbling poetry about a fairy land, Kortirion. Ill-prepared like many young soldiers who naively believed they’d sketch churches in Normandy, Tolkien was hurled into the Battle of the Somme where mustard gas, tanks, and flame throwers were no match for high-flown ideals. As a measure of how oblivious people at home were about fighting conditions, illustrated posters of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Land of Nod” were shipped to France to “brighten” the trenches.

illustrating Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem

Two of Tolkien’s best friends were killed. He himself contracted trench fever and was hospitalized for weeks. Yet the horrors he witnessed did not deter him from writing fantasy. While recuperating, he wrote “The Fall of Gondolin,” about an imaginary city he envisioned in a much larger narrative. He also wrote a shorter piece titled, “The Cottage of Lost Play.”

There I put down Garth’s book, intrigued by the image conjured in my head. I pictured a cottage in the woods, thatched, of course, with smooth river stones leading to the front door around which hollyhocks bloomed and wisteria drooped. The door was partly ajar. From inside came faint voices and laughter. My imagination turned the phrase “Lost Play” over and over like an old coin. Did it mean the irretrievable state of childhood? Rather than read Tolkien’s version, I was tempted to write my own. Not because I’m a writer, but because I’m human.

“Story is what the brain does,” Robert Storrs says in his book The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human and How to Tell Them Better. “Story emerges from human minds as naturally as breath emerges from human lips.” We experience our lives in “story mode,” creating little stories as we go about our day.

“Story is what the brain does,” Robert Storrs says in his book The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human and How to Tell Them Better. “Story emerges from human minds as naturally as breath emerges from human lips.” We experience our lives in “story mode,” creating little stories as we go about our day.

Educators know we learn to read by “seeing” images in our head. Storr explains to the rest of us that the brain processes written information by building models, the more specific the language, the more precise our models. Sometimes a name alone can trigger an image. When Bilbo and the dwarves reach the Mirkwood, my mind shows a pleasant forest. Then Gandalf warns them not to leave the path. Now the word becomes Murkwood, a dark and foreboding woods.

Our brains automatically make models when we read. Names heighten that tendency. As a boy, Will Storr and a friend pored over the maps in The Hobbit, lingering over the names: “Desolation of Smaug,” “West lies Mirkwood the Great — there are spiders.” They spent an entire summer making games from photocopies of the maps. The places felt “as real to us as the sweet shop in Silverdale Road,” he remembers. (I’m entranced by the luminous name of his childhood street!)

Place names, even without descriptions or explanations, instantly construct whole models. Storr quotes dialog from the movie Blade Runner: I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C‑beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser Gate. “Those C‑beams!” Storr adds. “That gate! Their wonder lies in the fact they’re merely suggested.”

Philologist Tolkien knew exactly what he was doing. Gondolin, with its hard “g” and weighty, falling syllables, brings to mind a once-powerful city gone to ruin. Places tagged during the Great War still carry solemn memories. The Somme. No Man’s Land.

George Stewart advised to let the shape of the land itself indicate what it could be called. Following Tolkien’s deep footprints, I’ll try to add meaning and evoke wonder to the blank spaces in my story with just-right names. If I think of anything nearly as brilliant as The Cottage of Lost Play, I’ll send up a flare.

Lovely, Candice; and now I’ve got Tolkien and the Great War in my library queue!

Thanks, Lynne. It’s an endless struggle to get to and through our work, isn’t it? At least it’s spring!