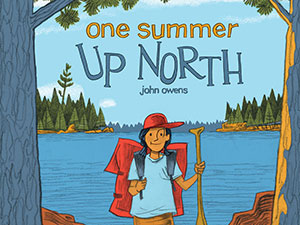

Once in a while a debut book comes across my desk and I’m too curious to put it into a to-be-read pile. I glance at the cover throughout the day until I can’t resist opening the book. What is it about? Am I going to like it? Then I keep turning the pages, marveling over the illustrations … and there are no words! I finish the book and immediately start over again. What have I missed on my first read-through? There’s so much to notice and look at more closely. One Summer Up North by John Owens is that sort of book. Reading that he teaches at the University of Minnesota, I knew my curiosity needed to be satisfied. And I get to share John’s answers with you.

Once in a while a debut book comes across my desk and I’m too curious to put it into a to-be-read pile. I glance at the cover throughout the day until I can’t resist opening the book. What is it about? Am I going to like it? Then I keep turning the pages, marveling over the illustrations … and there are no words! I finish the book and immediately start over again. What have I missed on my first read-through? There’s so much to notice and look at more closely. One Summer Up North by John Owens is that sort of book. Reading that he teaches at the University of Minnesota, I knew my curiosity needed to be satisfied. And I get to share John’s answers with you.

(photo: Louise Lystig Fritchie)

John, how did you decide on a story to tell?

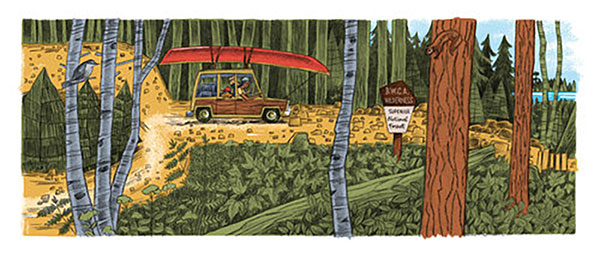

I decided on a story during my third canoe-camping trip through the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. After previous attempts at a couple of different concepts, this experience of wilderness and exploration in the BWCAW was the impetus I needed for my story. It was important to me for the story and illustrations to be evocative of that experience.

Where do you start with a two-page spread?

I start a two-page spread in my preliminary sketches with big horizontal shapes for unity and secondary vertical shapes to break up that space. Unlike facing pages with different images, the wide two-page spread is a perfect format for expressing the story of a wilderness area with big wide vistas, and sometimes intimate scenes which are integral to the story. In the book, these spreads alternate between land and water which provide a certain rhythm, interest, and variety when turning pages.

What do you do next?

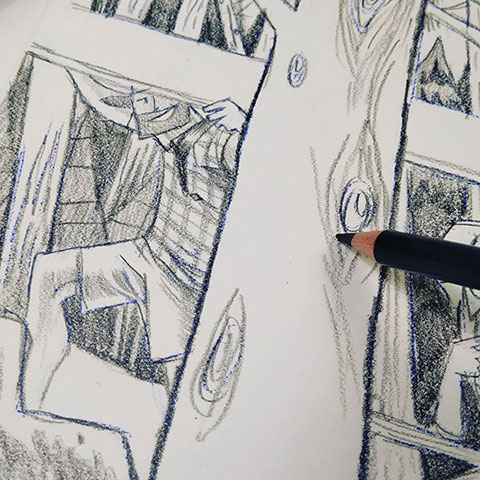

Build on my preliminary thumbnail sketches and notes. The sketches explore big design shapes, linear movement, balance, horizon, and light and dark areas in the composition. I also work on character development, figure placement and studies for certain flora and fauna. This is also the the time when I develop the style (medium, technique, and interpretation). My notes include everything from descriptive words to reminders and notations for variations or changes I may want to make and explore later.

Do you make mistakes or change your mind about what you’ve drawn?

I make mistakes and change my mind all the time! Process is all about exploring visual options and opportunities. Many of my sketches get re-drawn or changed. Some get discarded. I can’t know if something is working until I actually draw it on paper and revise it for comparison and contrast. If I was drawing digitally, I could easily correct mistakes by “undoing,” but I prefer drawing traditionally where I can see all my earlier concepts. This lets me compare and contrast them against each other. Often the process is long enough I find something I’ve drawn a year ago and have forgotten about and want to revisit. If I worked digitally, all of that would be lost. Process is the work. I don’t think the journey of discovery or creation is as rich an experience if you can’t see your progress from beginning to end. This is what I enjoy about seeing other peoples’ process work, the exploration and changes they’ve made. Fortunately we have a great resource for studying process work in children’s book literature at the University of Minnesota. This resides in The Kerlan Collection, a broad repository of illustrators’ children’s book work.

How do you make changes?

In the beginning I redraw and revise my thumbnail sketches. When I’m doing full-size sketches I will draw over the earlier marks. Sometimes I will erase a mark if it’s really not to my liking. I may even re-do the full size sketch if it’s just not working. Fortunately though, if my smaller sketches work as a design my larger sketches usually will too, and I can spend time exploring, adding detail and revisions.

This is a wordless book. Were you tempted to insert a word or two?

No. I really wanted to tell this particular story visually right from the start, through the procession of the characters in the wilderness, their gestures, and their expressions. Had my editor required it, I would have added short sentences where I could still interpret the story without relying on words much. This was only a passing thought because my editor immediately embraced my “wordless” concept.

What touches do you add to tell a story that’s progressing to a conclusion?

In One Summer Up North, those touches become a continuation of different scenes that advance toward evening and night, the close of day, and eventually wander back full circle to an earlier spread where the family moves out of the scene with just a slight adjustment in perspective. This concludes the story.

What makes a collection of two-page spreads into a story?

I think a collection of two-page spreads needs to have design continuity to move the story along. I did this by providing a strong horizontal design movement within the pages of the book. Some spreads work better than others, but you can easily see these big shapes in the composition if you’re looking for them.

What have you done in your life to prepare yourself for creating a picture book?

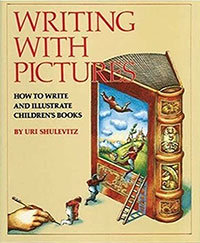

As a kid I was always intrigued by illustrations I saw created for children whether it was in Highlights magazine, Jack and Jill magazine, Saturday morning cartoons, or library books I borrowed from the bookmobile. I love the picture book as a visual form. The paper, the feel of the book, and even the smell of the ink, or old pages. A strong influence of mine was Uri Shulevitz’s book, Writing with Pictures. This book outlines steps, concepts, and structure in a way that I haven’t found anywhere else. Back in 2011, I took a weeklong intensive class for picture books taught by Caldecott Award winner, Eric Rohmann. This cemented my dedication to working toward creating my own book. The picture book is aspirational for me. By concentrating on drawing, working with different media, and pursuing illustration as my work, I have been able to achieve my dream!

As a kid I was always intrigued by illustrations I saw created for children whether it was in Highlights magazine, Jack and Jill magazine, Saturday morning cartoons, or library books I borrowed from the bookmobile. I love the picture book as a visual form. The paper, the feel of the book, and even the smell of the ink, or old pages. A strong influence of mine was Uri Shulevitz’s book, Writing with Pictures. This book outlines steps, concepts, and structure in a way that I haven’t found anywhere else. Back in 2011, I took a weeklong intensive class for picture books taught by Caldecott Award winner, Eric Rohmann. This cemented my dedication to working toward creating my own book. The picture book is aspirational for me. By concentrating on drawing, working with different media, and pursuing illustration as my work, I have been able to achieve my dream!

Where do you work?

Interestingly enough the original full size sketches for this book were drawn in a nondescript shared office space at the University of Minnesota where I teach. That semester I was teaching an early class and a late afternoon class so I had about 4 hours between the two which I spent eating my lunch and then just drawing, drawing, drawing. Mostly though I usually draw at my drawing table in an upstairs room of my house.

What’s your favorite tool for making art? Why?

My favorite tool for making art is a pencil. In this case, specifically a Faber Castell, Polychromos, Schwartz Black. This color pencil makes very rich black marks that when used on a Bristol board with some tooth, look much like lithographic marks. I love the look of the marks, I even love how the pencil feels when drawing with it.

Do you have your next project in mind?

I do have my next project in mind! In fact, it’s really three projects. Following up on One Summer Up North, I’m thinking of the other three seasons in the BWCAW, with winter coming next! Stay tuned…

Thank you, John, for answering my questions. Now I’m even more intrigued.

Are you, too, a curious reader? Please visit John Owen’s website for more information.