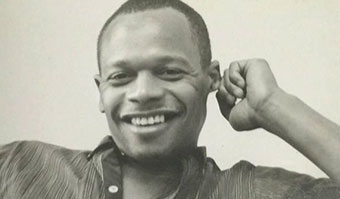

This month we want to celebrate the work of John Steptoe, brilliant artist and writer, who was born on September 14, 1950. His work is a year-round birthday present to all of us.

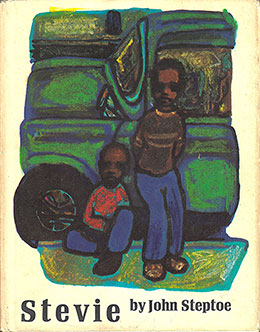

His first book, Stevie, was published by Harper & Row in 1969. Steptoe, in an interview in 1987, recalled that when he left high school a teacher suggested he show Ursula Nordstrom his portfolio. He soon did and she asked for a book. He had been thinking about the Stevie story for a couple of years. Harper published it when he was 19 years old. Life Magazine re-printed it. The book was celebrated as a “new kind of book for black children.”

His first book, Stevie, was published by Harper & Row in 1969. Steptoe, in an interview in 1987, recalled that when he left high school a teacher suggested he show Ursula Nordstrom his portfolio. He soon did and she asked for a book. He had been thinking about the Stevie story for a couple of years. Harper published it when he was 19 years old. Life Magazine re-printed it. The book was celebrated as a “new kind of book for black children.”

Now, we have the advantage of time and of a ground-breaking essay by Rudine Sims Bishop about the way literature can serve as a mirror to reflect one’s own self, a window into another culture, or a sliding glass door to allow readers to step into another culture in their imaginations. So, while we agree that Steptoe’s book should be read by Black children who need to see themselves mirrored in the books they read, we also know they should be read by all children who can move through the sliding glass door to the lives of children who are not themselves.i

And all children will understand Robert, the narrator of Stevie, who has to deal with the entrance of the younger child Stevie into his life. Stevie stays at Robert’s house Monday through Friday while his mother works. Robert is not happy about Stevie, “his old baby self,” living at his house. He plays with Robert’s toys, leaves footprints on Robert’s bed. When Robert goes outside to play with friends, his mother insists he take Stevie along. Robert’s friends call him “Bobby the Babysitter,” which makes Robert even more unhappy with this arrangement. Robert thinks Stevie has ruined his life and he doesn’t hesitate to tell him. “’I’m sorry Robert. You don’t like me Robert. I’m sorry,’ Stevie says.” Then one day Stevie’s parents came to tell Robert and his family the news that Stevie and his parents are moving. Stevie will not be staying at Robert’s house.

After Stevie is gone Robert realizes that he and Stevie did have good times, they ran in and out of the house together, they played on the stoop (“cowboys and Indians,” which we now see as an unfortunate choice), ate corn flakes together. Without thinking, Robert pours two bowls of cornflakes — one for himself and one for Stevie and as he reflects on his good times with Stevie, the corn flakes get soggy. “He was a nice little guy, my little brother Stevie.” We feel and understand his regret at not realizing that while Stevie was still in his life.

Steptoe was an artist and the illustrations are done in bold intense colors that draw our eyes into the page. Heavy black lines define the saturated colors and make us want to step into this world.

In 1987, John Steptoe was interviewed for an article in The Lion and the Unicorn. His concerns remain our concerns thirty plus years later.

“But black people are told they’re not talented. We’re not supposed to read or produce art; we’re supposed to play a little basketball. We are not allowed to make decisions. People have a definite way of thinking about working class people. But most good things that come out of this society come from the working class. So I bear the burden of talking about this to people. When I hold teacher workshops, I am not afraid to say I am racist. We are all racist. When I talk to librarians I tell them to write letters to editors saying, we are tired of what they’re publishing because all the kids we’re teaching are not Dick and Jane. They don’t live in that world, they don’t look like that, they don’t talk like that, and they are being hurt and need something better. I’m proud of Stevie because it addressed itself to working class kids. But I can’t just do that anymore. I have to explore other things.”

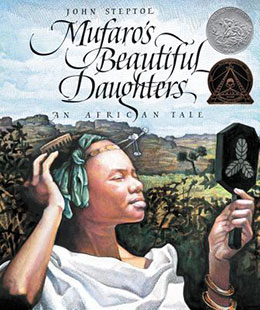

Steptoe wanted to explore his African roots. In the same The Lion and the Unicorn interview in 1987, Steptoe said of Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters:

Steptoe wanted to explore his African roots. In the same The Lion and the Unicorn interview in 1987, Steptoe said of Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters:

“… I wanted to find out about African culture. And my research took me to southeast Africa where there was trade with China as far back as 500 B.C. The story that I found was a fairy tale recorded by a missionary. It was originally called “The Story of Five Heads.” It took me about a year to research the story and about another year and a half to write and illustrate it. I hear tell you are supposed to do three books a year and support yourself that way, so that was not a great way to make a living. But the pictures are good quality, it took a lot of work and I feel good about it.”

The illustrations are more than “good quality.” They are arresting, awe-inspiring. Every detail of bird feather or flower is exquisitely rendered.

And the story itself is so satisfying. Based on an African folk-tale, it is the story of two beautiful sisters, Manyara and Niasha. But they are not the same. Manyara has a bad temper, seems always unhappy and teases her sister, “whenever her father’s back was turned.” Manyara expects to be queen and tells Niasha, “You will be a servant in my household.” Niasha has no ambitions to royalty and is happy growing millet, sunflowers, yams, and vegetables and befriending a small garden snake, Nyaka.

When the King announces that he is looking for a queen, Mufaro decides to accompany both of his daughters to the royal city. Manyara goes ahead at night, wanting to be the first and ensure her place on the throne. She encounters a hungry boy and does not offer food. She spurns an old woman’s advice.

Mufaro and Niasha are worried about Manyara’s disappearance but eventually set off for the royal city. When they encounter the hungry boy, Niasha gives him a yam. She gives sunflower seeds to the old woman.

At the royal city, Manyara rushes out to tell them of a monster sitting on the king’s throne. Niasha enters the throne room and finds the garden snake that she had loved.

He is also the king as well as the small boy and the old woman. He has witnessed the difference in the daughters and asks Niasha to marry him.

This is not an unfamiliar story, but we don’t need surprise to be satisfied. Perhaps we are hard-wired to love the justice in this book. Goodness is rewarded. Selfishness gets its right desserts. Would that that were always true!

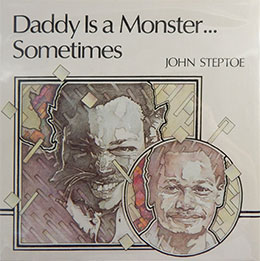

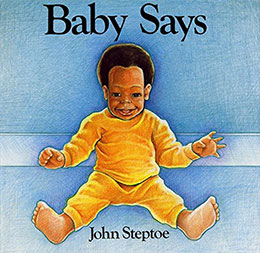

During Steptoe’s twenty year career (he died far too young at age 38) he illustrated 16 picture books, eleven of which he wrote himself and five by other authors (including All Us Come Cross the Water by Lucille Clifton, one of our favorite picture book writers). With many libraries still closed because of the pandemic, access to books can be limited, but one other Steptoe book available online is Baby Says.

The text consists of only a few words typical of very young children: Uh-oh, Here, No, no, Okay, and Baby says. The quiet art shows two children, one a baby in a playpen and the other, older, building with blocks on the floor outside the playpen. Baby throws a teddy bear out of the playpen, and the older boy returns it. Again baby throws the bear, again the boy returns it. The third time the bear hits the boy in the head, so he takes the baby out of the playpen. And, as babies delight in doing, the baby topples the blocks. A wordless spread shows the boy glaring at the baby, but on the next page baby charms the boy with a smile and a touch to his face, and they end up building blocks together.

The text consists of only a few words typical of very young children: Uh-oh, Here, No, no, Okay, and Baby says. The quiet art shows two children, one a baby in a playpen and the other, older, building with blocks on the floor outside the playpen. Baby throws a teddy bear out of the playpen, and the older boy returns it. Again baby throws the bear, again the boy returns it. The third time the bear hits the boy in the head, so he takes the baby out of the playpen. And, as babies delight in doing, the baby topples the blocks. A wordless spread shows the boy glaring at the baby, but on the next page baby charms the boy with a smile and a touch to his face, and they end up building blocks together.

As a Horn Book article in 2003 points out, Baby Says is part of a continuüm. Kathleen T. Horning writes,

“Over the span of his twenty-year career, Steptoe returned again and again to the complexities of sibling relationships, approaching the subject each time from a slightly different angle. What remained constant was his gift for realism, first in language and later in illustrations. What changed was his artistry: as his pictures became more detailed and realistic, he depended on them to carry more of the story, and the stories themselves were more carefully crafted. Ultimately, with Baby Says, he was able to tell a story with just six words: baby; says; here; uh, oh; okay; and no.

Every child deserves to hear themselves in books, and Steptoe let us hear their voices. Steptoe saw a “great and disastrous need for books that black children could honestly relate to … [and] I was amazed that no one had successfully written a book in the dialogue black children speak.”

Two of Steptoe’s books were named Caldecott Honor Books, and two won the Coretta Scott King Award for illustration. A Washington Post article calls Baby Says “a tender kiss good-bye — a gentle hug from Steptoe.”

We miss him.

Illustrated by John Steptoe

Illustrated by John Steptoe

Mother Crocodile by Rosa Guy, 1961

All Us Come Cross the Water

by Lucille Clifton, 1973

She Come Bringing Me That Little Baby Girl

by Eloise Greenfield, 1974

OUTside INside Poems by Arnold Adoff, 1981

All the Colors of the Race by Arnold Adoff, 1982

Article Links

“John Steptoe,” Wendy Watson, Wendy Watson’s Blog, 11 Nov 2014