by Vicki Palmquist

After reading Catherine, Called Birdy, readers will wonder about Edward, Birdy’s brother, and the books he was scribing at the monastery. In what type of book did Birdy keep her journal? Who taught her to write? Did she write in the same fancy script that her brother did at the monastery?

Birdy gives the reader clues about her journal: “The skins are my father’s, left over from the household accounts, and the ink also. The writing I learned of my brother Edward, but the words are my own.”

The author, Karen Cushman, describes the scriptorium in the monastery for us, “Edward works in Paradise. Beyond the garden, near the chapel, is a room as large as our barn and near as cold. Shelves lining the wall hold books and scrolls, some chained down as if they were precious relics or wild beasts. In three rows sit fifteen desks, feebly lit by candles, and fifteen monks sit curled over them, their noses pressed almost to the desktops. Each monk holds in one hand his pen and in the other a sharp knife for scratching out mistakes. On the desks are pens and quills of all sizes, pots of ink black or colored, powder for drying, and knives for sharpening.”

Catherine, Called Birdy is set in 1290 – 91 AD, a time when writing methods and scripts were changing a great deal. Life was moving from the medieval period to the Renaissance, although no one alive then would have known that or given those names to their lives. In the Author’s Note, Ms. Cushman writes, “Most people did not know what century it was, much less what year.”

It’s hard for us to think of the effort it took to create one book, the hours and hours of painstaking drawing of letters, which not only had to be readable but had to satisfy the fashions of the day, the standards for art and beauty that defined penmanship in that era.

This was approximately 200 years before the first book would be mechanically printed in England.

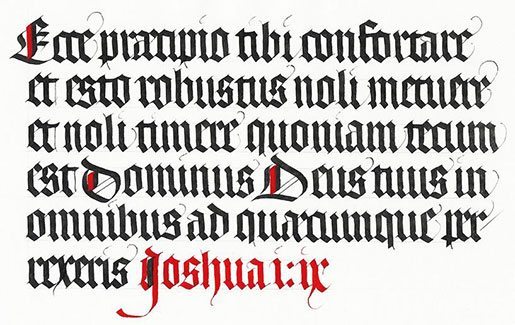

In the year in which Catherine, Called Birdy is set, the fashionable calligrapher used the penstrokes of Textura Quadrata, so called because its rhythmic vertical strokes created a texture on the paper … and was very difficult to read. There are many modern samples of this style on The Pensive Pen, a blog about calligraphy by Jamin Brown.

“The Gothic manuscripts … used the same pen stroke for many letters, and thus a word like “minimum,” with its unrelieved parade of vertical strokes, was almost impossible to read.” The Smithsonian Book of Books by Michael Olmert, Smithsonian Books, 1992, pg 75.

Here is an excellent video of a scribe, with a quill pen, creating letters in the Textura Quadrata or Blackletter style. Here are more samples.

In the classroom, you might talk about the differences between the way we write today and the time and care it is taking for the scribe in the video to write the alphabet.

Enjoy this sample page of calligraphy from John Stevens Design, a master calligrapher whose documents are created for special occasions as works of art.

Today, we open up our word processing program and scroll through the choice of fonts, making selections based on our mood or the message we’re hoping to convey. We may choose Fritz Quadrata or Caslon or Brush Script, most likely being unaware of the deep history behind each of these fonts. Today, Gothic Textura Quadrata is a font one can purchase for $12 online. Compare this to the art and care and skill of the scribe creating a page (without benefit of spellcheck or the delete key) to satisfy a rich patron who wanted a book in their house and paid for it to be handwritten.

“In the early middle ages literacy was viewed with some suspicion; actions definitely spoke louder than words, especially written words. These attitudes changed as the middle ages progressed; government became more dependent on records, and correspondingly the rest of society became increasingly aware that memories were not enough. It became important to have written proof of ownership or events. Latin was the language of government and official business, but by the fourteenth century an increasing amount of writing was being conducted in the vernacular.” A Medieval Book of Seasons, by Marie Collins and Virginia Davis, HarperCollins, 1992, pgs 25 – 26.

“From about 1150, however, all this began to change. Professional secular scribes and illuminators started to take over the book business. There is tantalizing evidence from the mid-12th century of traveling craftsman who must have hired themselves out to those who wanted manuscripts made.” The Smithsonian Book of Books by Michael Olmert, Smithsonian Books, 1992, pg 10.

“If a copyist made a mistake he put a series of fine dots under the offending word and then continued with his text. This avoided the creation of a horrific black cross-out, which would spoil the normal density of the letters on the page. Mistakes commonly occurred when the scribe was interrupted and then cast his eye forward or backward to a word similar to the one he had just finished. Christopher de Hamel, an expert in medieval manuscripts, says this usually happened when the scribe lifted his pen from the page for more ink (scribes tried to do a single sentence with each refill.) The Smithsonian Book of Books by Michael Olmert, Smithsonian Books, 1992, pg 74.

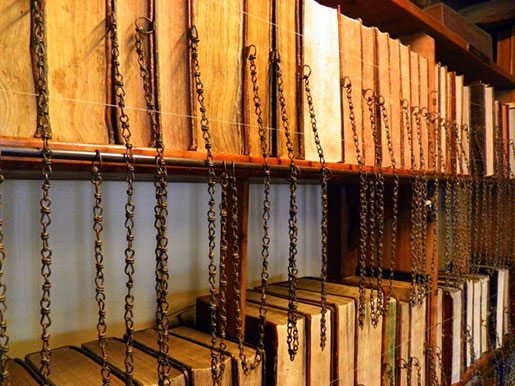

“Monastic scribes engaged in a variety of jobs. They prepared official documents, copied or recopied ancient or contemporary texts, produced missales for use in church or books of hours for rich patrons. Such lengthy, meticulous work was obviously a strain on the eyes, o it is not surprising that the first glasses were worn by monks. Manuscripts could be consulted in the library, but to prevent their being purloined by too individualistic monks they were sometimes changed to the shelves, as at Herford. This explains why in some monasteries copyists either worked in the library or in a scriptorium provided for compiling and copying texts.” Life in the Middle Ages, by Robert Delort, Edita Lausanne, 1972.

Movable type is credited to Bi Sheng, who lived in Bianilang during the Northern Song Dynasty. Somewhere between 1045 and 1058, he fashioned “3000 of the most common letters” out of clay, baked them in a kiln, and used them to print pages of type.

In 1234, Korean printers invented metal moveable type, which was more durable, and they printed the “oldest extant metal printed book” in 1377.” Be sure to take a look at the UNESCO Memory of the World for more details about this milestone that changed the world forever.

Here’s a fact that many of us learned in school: Johannes Gutenberg published the 42-line Christian Bible in 1455. His accomplishment was to invent a screw-type press that could use movable type to print pages quickly.

The first book to be printed in England was William Caxton’s edition of Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur in 1484. Caxton published “about 100 books, a number of which will live forever. The Canterbury Tales (1476−1478) was nearly a century old when Caxton printed them (Chaucer died in 1300). He probably printed them not because they were “literature” but because they contained popular, appealing stories. Caxton was a businessman. Entertainment was more important to him than erudition.” The Smithsonian Book of Books by Michael Olmert, Smithsonian Books, 1992.

And what happened to those books? Did Birdy’s house have a shelf with books on it, script written by Edward? Here’s a public library 400 years later at Wimborne Minster in England.

“Situated within the Minster, this was one of Britain’s first public libraries, established in 1686 in the room previously the Treasury, which housed the wealth of the Minster until it was confiscated by Henry VIII.

“Among the earliest collections of the library, which we see here, were donated by Rev. William Stone on condition that the books were chained to the shelves — he wished that his items be available not only to the clergy but also to ‘the better class of person in Wimborne.’ He provided money for the chains and also stipulated that the existing works also be chained, lest they be pilfered by the less scrupulous.

“Stone’s collection is entirely ecclesiastical, but later collections have a variety of subjects, from architecture to wine pressing and even how to kill an elephant.

“These are Victorian chains but there are two originals remaining. Because the chains are attached to the edges of the book covers, rather than the spines which would become easily damaged, the books face inwards.” From Geograph: Wimborne Minster, Dorset, Great Britain.

References

Alphabet Gothique, Textura Quadrata. Gerard Caye. YouTube video.

Art of Calligraphy: a Practical Guide to the Skills and Techniques. David Harrison. DK Books, 1995.

Catherine, Called Birdy. Karen Cushman. Clarion Books, 1994.

China Culture.org, “Bi Sheng.”

Friendly Korea, my friend’s country. “The Greatest Invention, Movable Metal Type Printing and Jikji.”

Geograph website.

Life in the Middle Ages. Robert Delort. Edita Lausanne, 1972.

Malory Project. Facsimile version of William Caxton’s 1485 edition of Le Morte d’Arthur.

Medieval Book of Seasons. Marie Collins and Virginia Davis. HarperCollins, 1992.

Memory of the World. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.

Oregon State University Libraries, Special Collections & Archives Research Center. “Treasures from the McDonald Collection, the Incunable Era, the Gutenberg Press.”

Pensive Pen, a blog about calligraphy. Jamin Brown.

Smithsonian Book of Books. Michael Olmert. Smithsonian Books, 1992.

Vicki, this is a terrific post – thanks so much. Am hereby calling my writing room The Scriptorium.

Good to hear from you, Tricia! Hereafter I shall think of you writing in The Scriptorium. I hope you have central heating!

Wow! That’s some mighty impressive research! Thanks for sharing it. I haven’t read the book in many years, but I remember loving it. You nudged me into putting on my gigantic pile of books that I hope to get to in the near future … or when I retire!

It’s a good book for re-reading, Pat. I love it because it makes me laugh … and Ms. Cushman is a good storyteller.

Very, very interesting and well-written, Vicki. A joy to read.

Thank you, Eileen. I love a good research project. And I discovered so much beyond Gutenberg and his press.

Enjoyed this interesting post, Vicki, with its well-researched links.

Thank you, Natalie. And so much information I hadn’t come across before … it was an enlightening project.