To celebrate our fortieth anniversary this year, we decided to take a Big Trip. My husband suggested Paris. “Cornwall,” I said. “Someplace old.” Not that Paris isn’t old. Instead of a crowded city, I wanted winkles and pasties, lost gardens and standing stones, piskies and Tintagel castle. He agreed and I began putting together a trip that would send us back in time.

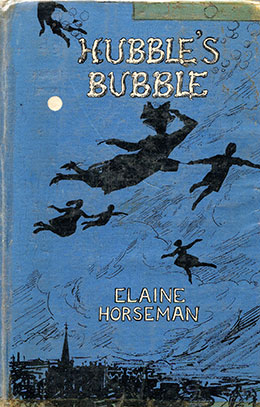

My motives weren’t entirely pure. True, I’ve been an Anglophile ever since I read the British children’s fantasy Hubble’s Bubble at the age of eleven and started saving pennies to go to Wales and Scotland. Currently I’m writing my first magical realism middle-grade novel. Building the world of my story has taken nearly three years, yet the book’s foundation feels as stable as shivering sands. By tramping over ancient lands, I hoped Cornwall’s mythology would seep through the soles of my Sketchers and I’d bring some back with me.

My motives weren’t entirely pure. True, I’ve been an Anglophile ever since I read the British children’s fantasy Hubble’s Bubble at the age of eleven and started saving pennies to go to Wales and Scotland. Currently I’m writing my first magical realism middle-grade novel. Building the world of my story has taken nearly three years, yet the book’s foundation feels as stable as shivering sands. By tramping over ancient lands, I hoped Cornwall’s mythology would seep through the soles of my Sketchers and I’d bring some back with me.

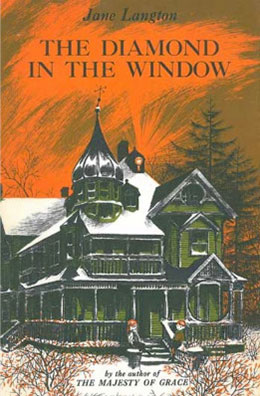

As much as I love America’s history and varied landscapes, I fret that the U.S. isn’t — well, Britain. America has, as New England fantasy writer Jane Langton once wrote, “less history to draw on … It is bald of mythology, bare of folk tale. Its open fields are not marked by standing stones.” We do have Native American folklore and the tall tale adventures of larger-than-life characters such as Paul Bunyan and John Henry. But those stories are not part of my background.

Langton’s essay is more than thirty years old and much has changed. Many fantasies today give readers passports to worlds beyond medieval Europe, inspired by African, Asian, and indigenous American cultures. My book is set in Virginia, deeply linked to my English roots, a place and voice I know. But Virginia has no dead kings buried with broken swords, no sleeping dragons under the hill, no fairies. How will I saturate the landscape with magic?

When I think back, I didn’t always notice the settings of childhood books. The opening line of Edward Eager’s Seven-Day Magic hooked me right away. “‘The best kind of book,’” said Barnaby, “‘is a magic book.’” I agreed and ripped through the Half-Magic series, not caring that the books are placed vaguely in America (Ohio and Connecticut, Eager’s stomping grounds).

When I think back, I didn’t always notice the settings of childhood books. The opening line of Edward Eager’s Seven-Day Magic hooked me right away. “‘The best kind of book,’” said Barnaby, “‘is a magic book.’” I agreed and ripped through the Half-Magic series, not caring that the books are placed vaguely in America (Ohio and Connecticut, Eager’s stomping grounds).

Midwesterner Eager grew up with the Oz books, the first true American fantasies for children. When he had his own children, he discovered E. Nesbit’s books, which he praised for the “dailiness of the magic. Here is no land of dragons and ogres or Mock Turtles and Tin Woodmen … The world of E. Nesbit is the ordinary or garden world we know, with just the right pinch of magic added.” Everyday magic, set wherever, suited me fine.

Yet when I found Jane Langton’s A Diamond in the Window, I met an opening that left no question about its setting: “Edward Hall sat under the front porch of the big house on Walden Street in Concord, Massachusetts, and thought about his two ambitions in life.” By page 4, I’d learned Concord was the site of the first battle of the Revolutionary War, Walden Pond was nearby, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Louisa May Alcott, and Henry David Thoreau, whoever they were, had lived there. This Virginia kid, clueless about New England, was intrigued. Not far into the story — a delightful combination of fantasy and mystery — the children’s naïve Uncle Freddy quotes Emerson to the trash collector:

Yet when I found Jane Langton’s A Diamond in the Window, I met an opening that left no question about its setting: “Edward Hall sat under the front porch of the big house on Walden Street in Concord, Massachusetts, and thought about his two ambitions in life.” By page 4, I’d learned Concord was the site of the first battle of the Revolutionary War, Walden Pond was nearby, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Louisa May Alcott, and Henry David Thoreau, whoever they were, had lived there. This Virginia kid, clueless about New England, was intrigued. Not far into the story — a delightful combination of fantasy and mystery — the children’s naïve Uncle Freddy quotes Emerson to the trash collector:

“Oh, call not Nature dumb!

The trees and stones are audible to me …”

It’s a funny scene, but the quote set me to wondering. I’d often thought trees talked (it turns out they do!) and sometimes worried when I walked on rocks — did they hurt? The Diamond in the Window has magic, but it also has nature, which was more accessible to me. As a child, there was so much I wanted to know about the ground beneath my feet, the trees stretching toward the sky, the clouds and weather.

In Langton’s essay, she admits British fantasy writers can tap into “the thick intertwining of field and forest with myth and history.” She mentions that Scottish writer Mollie Hunter once told her that fantasy “could only be composed by someone standing upon a countryside drenched in myth and folklore.” Really? I went flying to an essay by Mollie Hunter in which she credits legends, “a succession of folk memories filtered through the storyteller’s imagination,” as the basis for true fantasies.

In Langton’s essay, she admits British fantasy writers can tap into “the thick intertwining of field and forest with myth and history.” She mentions that Scottish writer Mollie Hunter once told her that fantasy “could only be composed by someone standing upon a countryside drenched in myth and folklore.” Really? I went flying to an essay by Mollie Hunter in which she credits legends, “a succession of folk memories filtered through the storyteller’s imagination,” as the basis for true fantasies.

Virginia, I’m afraid, sadly lacks supernatural beings such as Celtic fetches and wraiths. But it has an abundance of nature, the kind E.B. White tapped into by watching ordinary spiders and pigs and rats at his Maine farm. Langton argues that “nature taken pure, nature in its simplicity and silent grandeur” carries its own brand of magic. Instead of longing for standing stones, I’ll be happy to extract “marveling wonderment” from the seashell-capped Blue Ridge Mountains, horse-pastured Piedmont, and osprey-nested Chesapeake Bay.

As for Cornwall, we discovered that the five-hour car trip after an overnight flight to Heathrow, in which the only age-qualified driver (who can barely park her small pickup) would never manage driving stick-shift from the left seat on the left-hand side of the road. It’s okay. We will gladly take a bus from London to Stonehenge. My Sketchers will never know the difference.

Dear Ms. Ransom,

Thank you for this interesting article I’m curious if you can share the essay titles by Mollie Hunter and Jane Langton. As a student of children’s literature, I’m interested to read their perspectives. Thank you, Kristen

Hi Kristen: Sorry to take so long to get back to you. Jane Langton’s essay, “A Hair’s Breadth Aside,” is found in Innocence & Experience: Essays and Conversations on Children’s Literature, edited by Barbara Harrison and Gregory Maguire (1987). Mollie Hunter’s essay, “One World” is from her book, Talent Is Not Enough: Mollie Hunter on Writing for Children (1976).