We have been thinking of trees — green, leafy, blooming, buzzing trees. It’s not that we’re tired of winter. We love winter. Phyllis even has snowshoes — and uses them! Jackie loves walking in the snowy quiet and the nearly monochromatic landscape. We both love candles, sweaters, and hot soup. But every now and then we think of green. This month we decided to write about trees.

We have known kids, and others, who talked to trees. And maybe the trees talked back. The trees in Old Elm Speaks by poet Kristine O’Connell George (illustrated by Kate Kiesler) tell their own stories. The book begins with oak’s introduction. “I’ve been wondering//when you’d notice/me standing here. //I’ve been watching you grow taller. / I have grown too. /My branches/are strong. // Step closer./Let’s see. How high/ / you can/climb.”

We have known kids, and others, who talked to trees. And maybe the trees talked back. The trees in Old Elm Speaks by poet Kristine O’Connell George (illustrated by Kate Kiesler) tell their own stories. The book begins with oak’s introduction. “I’ve been wondering//when you’d notice/me standing here. //I’ve been watching you grow taller. / I have grown too. /My branches/are strong. // Step closer./Let’s see. How high/ / you can/climb.”

Jackie: One of my favorites in this book is “Tree Traffic,” written a bit like a traffic report we might hear on the radio. “Major tree traffic today — /commuters in both directions, //rippling up and down, /tails unfurled. //The treeway is heavily squirreled.” I love the puns — treeway, the rhymes — unfurled, squirreled. It’s fun to read and fun to say out loud.

And finally, when Old Elm speaks, we are reminded of the turning of time and seasons passing into years: “It is as I told you, Young Sapling. //It will take autumns of patience/before you snag/your/first/moon.” This book will make readers want to try their own tree poems.

Phyllis: Kate Kiesler’s warmly colored full-page art invites us in to climb trees, swing under hammock-holding trees, pick plums from trees offering fruit over a fence, or find tree seedlings sprouting unexpectedly in a pumpkin patch (“the dirt was sweet and soft — /I guess/I must/have/dozed/off…”). The poem “Hide and Go Seek” takes on the concrete shape of elbows sticking out from a child hiding behind a too-slender tree, and the lines of “Tree’s Place” shape a tree, trunk and crown. I love, too, how the narrator of “Leaving Woods’ Lake, Colorado” plans to take the whole place home with them in the car: pines, lake, rowboat, squirrel, dinner bell, log cabin, columbine — “My brothers will ride home/in the trunk.”

These voices of trees are solemn, funny, friendly, playful, wise, which I imagine trees would be if we could listen hard enough to hear them speak. This past winter I found a tree with a doorway I could crawl inside of, and although I didn’t hear the tree’s heartbeat, as the narrator of “Kings Canyon” does, I plan to go back and listen harder.

Jackie: Another tree I’d like to converse with is the Treaty Oak that grows in Austin, Texas. And I want to listen as this tree in our dear friend Ellen Levine’s book The Tree That Would Not Die (illustrated by Ted Rand) tells us its story. The Treaty Oak is hundreds of years old and was once one of the Council Oaks, reputedly the site of gatherings of tribes of First Peoples. When this oak was the last one standing, people say it was where Stephen Austin signed a treaty with leaders of First Peoples’ tribes. The tree was purchased for one thousand dollars in 1927 by the City of Austin. People picnicked, danced, celebrated under that huge old oak until 1989, when a man poured a powerful poison around the base of the tree. He used enough poison to kill a hundred trees. No one thought this tree could live. People came to hug the tree, to bring flowers — even chicken soup. Arborists dug out the soil around the roots and washed them. They sprayed the tree, which could not shade itself, with water. Two-thirds of the tree died and had to be pruned away.

Jackie: Another tree I’d like to converse with is the Treaty Oak that grows in Austin, Texas. And I want to listen as this tree in our dear friend Ellen Levine’s book The Tree That Would Not Die (illustrated by Ted Rand) tells us its story. The Treaty Oak is hundreds of years old and was once one of the Council Oaks, reputedly the site of gatherings of tribes of First Peoples. When this oak was the last one standing, people say it was where Stephen Austin signed a treaty with leaders of First Peoples’ tribes. The tree was purchased for one thousand dollars in 1927 by the City of Austin. People picnicked, danced, celebrated under that huge old oak until 1989, when a man poured a powerful poison around the base of the tree. He used enough poison to kill a hundred trees. No one thought this tree could live. People came to hug the tree, to bring flowers — even chicken soup. Arborists dug out the soil around the roots and washed them. They sprayed the tree, which could not shade itself, with water. Two-thirds of the tree died and had to be pruned away.

This lovely book, published in 1995, could not answer the question whether the tree would survive. But we know it has. The poisoner has passed, but the tree continues to live and has produced acorns. It has been cloned. It is still there to connect Texans to their history.

Phyllis: The richly colored illustrations show the tree growing larger and larger as history happens around it. The treaty oak survives with the help of a whole community of caring people. Whenever I read one of Ellen’s books, it is as though she is here with us again, fighting for justice, caring about community, making us all laugh as she shares her joy in life. We miss her.

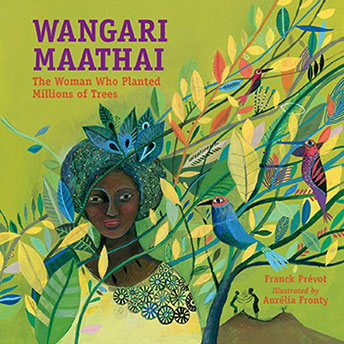

Jackie: Wangari Maathai, winner of the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize, planted trees. She has been written about several times in picture books for children. Among the books are Mama Miti, written by Donna Jo Napoli and illustrated by recent Caldecott recipient Kadir Nelson; Planting the Trees of Kenya written and illustrated by Claire A. Nivola; Wangari’s Trees of Peace, written and illustrated by Jeanette Winter. We want to focus here on Wangari Maathai The Woman Who Planted Millions of Trees, written by Franck Prévot and illustrated by Aurélia Fronty.

Jackie: Wangari Maathai, winner of the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize, planted trees. She has been written about several times in picture books for children. Among the books are Mama Miti, written by Donna Jo Napoli and illustrated by recent Caldecott recipient Kadir Nelson; Planting the Trees of Kenya written and illustrated by Claire A. Nivola; Wangari’s Trees of Peace, written and illustrated by Jeanette Winter. We want to focus here on Wangari Maathai The Woman Who Planted Millions of Trees, written by Franck Prévot and illustrated by Aurélia Fronty.

This beautiful book is a full accounting of Wangari Maathai’s life. In the prologue Prévot writes: “When Wangari planted a large-leafed ebony tree or an African tulip tree, she was reminded of her own roots. She was born in 1940 in the little village of Ihithe, across from the majestic volcano Mount Kenya, which her people consider holy.”

Her home was surrounded by forests. She had her own little garden and was a conscientious helper to her mother. But, unlike many girls in Kenya, she was sent to school. “She received her high-school diploma at a time when very few African women even learn to read.” When Sen. John F. Kennedy invited young Kenyans to pursue studies in the United States, Wangari traveled to the United States. She studied in the U.S. for six years. When she returned to Kenya, she found a different home. So many trees had been cut that wild animals were rare. Plantations had replaced farms and people were going hungry.

In 1977, Wangari created the Green Belt Movement. She raised money and created tree nurseries in villages across Kenya. She asked the village women to care for the nurseries and gave them money for each tree that grew. She opposed the plans of President Daniel arap Moi to build a statue of himself in a park in Nairobi and to set up a real-estate project in a large forest — and she won. But she also went to jail several times. But she continued to plant trees. Eventually, Daniel arap Moi was defeated and Kenya had a new constitution. Maathai was elected to Parliament and appointed “assistant minister of the environment, natural resources, and wildlife.”

In 2004 she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for the countless seeds of hope she planted and grew over the years.”

Extensive back matter and bibliography will be useful to readers who want to know more about this remarkable woman.

Phyllis: While I knew about Wangari’s work of planting trees, I knew nothing about the political side of her efforts. “Wangari wants to make democracy grow — like trees,” Prévot writes. She demonstrates, stands up to a powerful government, is imprisoned, receives death threats. When President Daniel arap Moi tries to pit tribe against tribe to maintain his hold on government, Wangari and the Green Belt Movement offer saplings to neighboring tribes to symbolize peace. Through all the struggles and eventual triumphs, she never forgets her mother’s words that “a tree is worth more than its wood.” Aurélia Fronty’s vivid, double-page art is a joy.

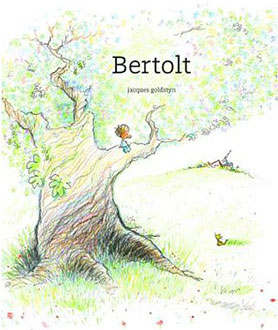

Jackie: Finally, a book about a single tree — a tree a young boy has named “Bertolt.” And the book is called Bertolt. Written in French and illustrated by Jacque Goldstyn, translated by Claudia Zoe Bedrick, the book doesn’t begin with a tree. It begins with a lost mitten. Our protagonist has lost a mitten and must replace the lost item with a mitten from “lost and found.” Of course, it doesn’t match. “Who cares. /I like it this way. Wearing two different mittens is kind of funny.”

Jackie: Finally, a book about a single tree — a tree a young boy has named “Bertolt.” And the book is called Bertolt. Written in French and illustrated by Jacque Goldstyn, translated by Claudia Zoe Bedrick, the book doesn’t begin with a tree. It begins with a lost mitten. Our protagonist has lost a mitten and must replace the lost item with a mitten from “lost and found.” Of course, it doesn’t match. “Who cares. /I like it this way. Wearing two different mittens is kind of funny.”

But, he goes on, when you are different people laugh, “or even worse.” The narrator tells us he isn’t like other people. He doesn’t mind being alone. “I love doing lots of things by myself, but I love climbing my tree best of all.” He has named the tree Bertolt and guesses it to be about five hundred years old. Climbing Bertolt is “like climbing a secret ladder.” Up in the tree the view is great. Our hero can watch the goings-on in the village. And there are squirrels, a crow, an owl, insects, and birds. He even loves the tree during storms.

But one spring, Bertolt does not leaf out. “Days pass. Then weeks. /I wait. I hope. I pray. / But finally I have to accept it. / Bertolt is dead.”

What to do? He wants to keep Bertolt from being turned into toothpicks. The Lost and Found…some stolen clothes pins…And Bertolt blooms!

Phyllis: I love the illustration of Bertolt leafed out in many different colored mittens. I love, too, that this is not a book that sets out to teach us about death (although it does not shy away from it, either). A boy loves a tree, the tree dies, the boy honors his friend and makes it beautiful again while still accepting that the tree is no longer alive.

Jackie: This little book is like a shared secret between the narrator and the reader. It reminds us of the fun of being by oneself, of the sadness of change, and the power of creative thinking.

It reminds us, too, as all of these books do, of the joy of trees — in any season.