It was the early eighties and I was grappling with my first middle grade novel, a pitiful imitation of Daniel Pinkwater’s Alan Mendelsohn, the Boy from Mars. The boy in my aptly-titled “The Doomsday Kid” played Dungeons and Dragons and attended a rock concert that ended in a bottle-and-can riot. For “research,” I tried to teach myself D&D and dragged my husband to a Bad Company concert that ended in his temporary deafness. No publisher would touch my thorny mess of a manuscript.

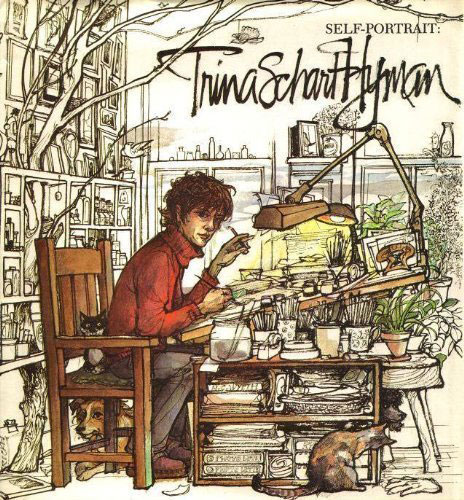

In 1981, I bought Trina Schart Hyman’s Self-Portrait. The Addison-Wesley series focused on children’s book illustrators who “talked” about their work in words and art. Trina’s life is rendered in exquisitely-written short chapters with watercolor vignettes that are at once deeply personal yet as delicately distant as the fairy tales she loved.

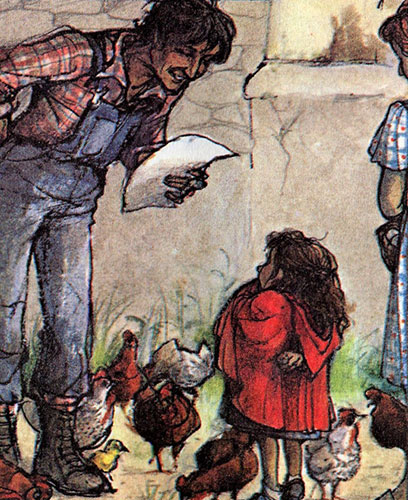

A fearful child, Trina needed to be Red Riding Hood for an entire year. She needed to see Bruegel’s “The Unfaithful Shepherd” in the Philadelphia Museum of Art to know there are wolves. She needed to create a real fairy for her little sister, who believed Trina’s made-up fairy stories. Later, she needed to leave home, become an artist, get married, and go to Sweden, where trolls were frozen in stones, and she “felt their desperate, ancient sorrow.”

I’d never read anything like Self-Portrait. Like Trina, I was a fearful child. I, too, had trouble in school because I preferred to read and draw. But I never believed in fairies or angels or trolls. Yet her sincerity made me question why I was wasting my time on a book that had nothing to do with me or anything I cared about. What did I know about bottle-and-can riots, or Dungeons and Dragons, or being a boy? My life needed to be in my work.

I began writing about things that mattered to me. It took a while, but I got there. I followed Trina’s career closely and, in 1985, I met her in person when she spoke at the annual luncheon of the Children’s Book Guild of Washington, D.C. As a member, I insisted on being Trina’s “handler.” I fretted over what to wear, settling on a Gunne Sax outfit — red printed flannel tunic with a white pilgrim collar, floppy black bow, and black-and-white check flannel underskirt. I cringe now describing such a get-up, but when I walked over to Trina, she said my dress was the most beautiful she’d ever seen. I was Red Riding Hood.

Trina Hyman was a working artist. She illustrated educational books, greeting cards, magazine covers, and dozens of trade books. Three of her titles were Caldecott Honors, and St. George and the Dragon won the 1985 Caldecott.

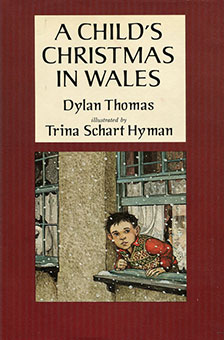

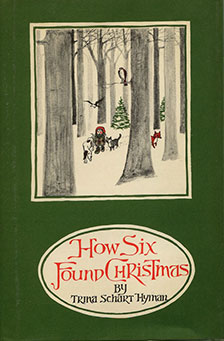

Most of my holiday books feature her art: Christmas Poems, A Child’s Christmas in Wales, A Christmas Carol, and, my favorite, How Six Found Christmas, a fable Trina wrote and illustrated for her daughter. A friend gave me a first edition of this lovely little book. When first I saw the little girl in the snowy woods on the cover, I was carried back to the Christmas I was nine. My older sister had left home that summer. December descended, stark and lonely. Christmas wouldn’t be the same without my sister, who whispered stories through the heat register that connected our bedrooms.

Most of my holiday books feature her art: Christmas Poems, A Child’s Christmas in Wales, A Christmas Carol, and, my favorite, How Six Found Christmas, a fable Trina wrote and illustrated for her daughter. A friend gave me a first edition of this lovely little book. When first I saw the little girl in the snowy woods on the cover, I was carried back to the Christmas I was nine. My older sister had left home that summer. December descended, stark and lonely. Christmas wouldn’t be the same without my sister, who whispered stories through the heat register that connected our bedrooms.

Among my mother’s holiday trimmings, I found a gauzy pink angel package tie. I slipped it in the pocket of my coat and walked into the woods beyond our garden. Gray-blue light cloaked the clearing where a tree had fallen. I sat on the trunk and took the tiny decoration from my pocket. “You are the angel of Christmas,” I told her. She understood I needed her. A thin lozenge of sun appeared and brightened the woods.

At the end of her memoir, Trina says, “Everything I have told you is a fairy tale. Life is magical … Nothing is safe and everything changes.” But the accompanying illustration reveals there will always be family and friends, cats and dogs, food to fix and stories to tell. I savor this book each year, especially the gray-blue winter pond scene in the first chapter and these words: “It seemed then that it was always the week before Christmas, the sky was full of snowflakes ready to fall, and angels were perched on the barn along with the pigeons.” Look closely and you’ll see faces and wings in the dark-gray clouds.

At the end of her memoir, Trina says, “Everything I have told you is a fairy tale. Life is magical … Nothing is safe and everything changes.” But the accompanying illustration reveals there will always be family and friends, cats and dogs, food to fix and stories to tell. I savor this book each year, especially the gray-blue winter pond scene in the first chapter and these words: “It seemed then that it was always the week before Christmas, the sky was full of snowflakes ready to fall, and angels were perched on the barn along with the pigeons.” Look closely and you’ll see faces and wings in the dark-gray clouds.

Trina Schart Hyman left this life in 2004 at the age of 65, one year younger than I am now. I’ve learned that everything does change, and wonder if angels still watch. With each passing Christmas, I remember loved ones who are no longer here to share the season, including Trina, who unknowingly became my angel when I needed her most.

LOVE. I wish I could have met her.