The fairy tale follows a definite pattern, rewards and punishment, escape from danger, and closure … its defining characteristic.

from Tales of Innocence and Experience by Eva Figes

I sat on a rusted swing hung from an I beam in our basement with a heavy book on my lap. I’d found the book, one of several volumes of the 1949 edition of The New Wonder World, in a box under the zinc-topped table where my stepfather sliced hams. I was ten and lonely because my only sister had left home a year earlier.

Rocking back and forth, I lost myself in Andersen’s “The Tinder Box.” I figured a tinder box was like a cigarette lighter with the ability to summon enormous-eyed dogs that granted wishes. Next I read “The Princess and the Pea.” Back then I couldn’t stand clothing or covers touching my neck and identified with the bruised princess, only my former bruises hadn’t been caused by a pea under twenty mattresses.

Rocking back and forth, I lost myself in Andersen’s “The Tinder Box.” I figured a tinder box was like a cigarette lighter with the ability to summon enormous-eyed dogs that granted wishes. Next I read “The Princess and the Pea.” Back then I couldn’t stand clothing or covers touching my neck and identified with the bruised princess, only my former bruises hadn’t been caused by a pea under twenty mattresses.

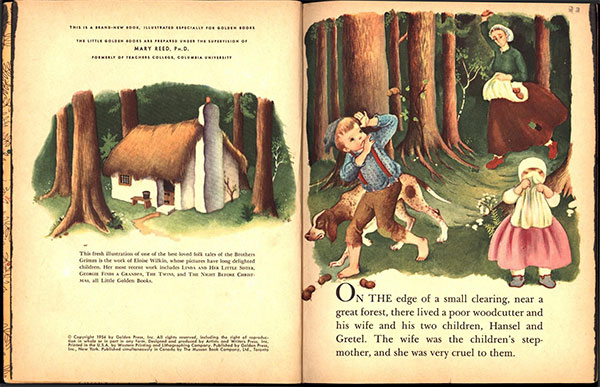

Before I learned to read, I decoded Hansel and Gretel, a Little Golden Book, from Eloise Wilkins’ illustrations. My sister and I had lived that story. We looked nothing like those dumpling-cheeked children. I was five when our mother remarried, and we moved from the gingerbread house to a new brick house in the forest. Trees with goblin shadows terrified me. As I grew used to my kind, gruff stepfather and the trees he identified by name, I realized I’d left the real goblins behind.

Recently I read a book by Holocaust survivor Eva Figes, who recounts reading fairy tales to her granddaughter. Between the lines in this tender, spare memoir is Figes’ story of fleeing Germany as a young girl, and her grandmother who didn’t make it out. She writes:

The earth continues to turn and there are signs of spring. A haze of palest green in the empty trees. A promise unexpectedly kept. My radio speaks of global warming, extinction of species. My heart, on the other hand, craves rhythms. Fluctuations of light, wet pavements, night and day. The telephone ringing, and a child’s voice speaking of birthday parties. Generations living out their lives in an orderly cycle, without fuss. The children, I tell [my granddaughter], back from the forest, lived happily ever after.

Though I was late coming to fairy tales, and never had anyone read or tell me a bedtime story, my mother related family stories while she fixed supper. Like the day a woman came to the door selling encyclopedias, and my three-year-old sister darted outside in her birthday suit. The steely saleswoman declared what she’d do that kid. My mother bought the encyclopedias, then chased after her quick-as-a-fox child. All this happened before I was a twinkle in my mother’s eye.

I used to love that expression, believing that once my mother had a willful daughter while her quiet, good daughter waited on a distant star. Yet when I finally arrived, I stayed in the shadow of my sister who had enough sparkle to light up Paris. It was inevitable that she would flee the woods to marry her prince, leaving me with a broken heart and storybooks.

Years later, I grew up to write my own stories. Then came the pandemic, bouts with Covid, my sister’s terminal cancer, and a fractured world I no longer understood. I longed to return to the woods. Instead, I returned to fairy tales, the place where I began, by enrolling in an online M.A. program to study imaginative literature. I dropped the program when I learned students were required to participate in discussions twice a week. Given my sister’s steady decline, I couldn’t commit to such a schedule. If I’d been in a fairy tale, I would have wept silently under a juniper tree. I flat out sobbed for a solid hour on my computer keyboard.

Later I signed up for a short-term Zoom course on the role of animals in fairy tales. I found myself unable to answer questions about symbolism and relationships between characters because I read from a writer’s perspective. Any symbols in my work are unintentional, ferreted out by the reader. I felt stupid, mute as the sister weaving nettle shirts to save her transformed brothers. Mute as I’d once been as a child in the gingerbread house.

In the mirror, I see a face gray from an endless winter. Craving sparkle like a starving person desires a twenty-course dinner, I bought myself silver bracelets and rings with seductive names like Fairytale and Princess Tiara, studded with tiny star-like cubic zirconias.

My sister has been living in a Grimm’s tale the past two and a half years. She cannot eat. She cannot speak. Goblins squeeze her lungs and wolves gnaw her feet. The tasks set before her to get through each night and day are like climbing a glass mountain, yet still she fights.

If I had a tinder box, I’d strike it three times, summon all three dogs and wish — beg, really — to give my sister orderly rhythms, her voice back, an endless spring. I’d gladly trade my borrowed sparkle for a galaxy of diamonds and set her in its very crown.