“It wasn’t too fantastic. That’s what you need: a fairly down-to-earth story that people can associate themselves with.”

—Walt Disney, on choosing Snow White as his first animated feature

When I was ten, I wanted to be a detective-veterinarian-artist-writer-ballet dancer. Never mind I couldn’t stay up late, stand the sight of blood, or ever had a single dance lesson. Ten-year-olds view the world as limitless. When I was a teenager, my dreams shifted to more specific: a writer of children’s books and an animator for Walt Disney Studios.

Like millions of kids in the 60s, I was glued to our TV on Sunday nights to watch Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. I’d never seen any Disney movie in the theater, but this television program showed tantalizing snippets of the animated features. In high school, I discovered Walt Disney: The Art of Animation in the public library. I pored over sketches, storyboards, backgrounds, and full-color art. I studied the work of in-betweeners, background artists, layout artists, concept artists, inkers, and painters, who seemed like family.

Like millions of kids in the 60s, I was glued to our TV on Sunday nights to watch Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. I’d never seen any Disney movie in the theater, but this television program showed tantalizing snippets of the animated features. In high school, I discovered Walt Disney: The Art of Animation in the public library. I pored over sketches, storyboards, backgrounds, and full-color art. I studied the work of in-betweeners, background artists, layout artists, concept artists, inkers, and painters, who seemed like family.

I fell so hard I left a dent in the floor. This was what I wanted to do, along with writing children’s books. I promptly wrote to Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California, letting them know I was available. My handwriting clued them I was just a kid, though I did receive a reply which said: Finish school, then submit samples to their special art school in California. No problem! Never mind I lived in the sticks in Virginia.

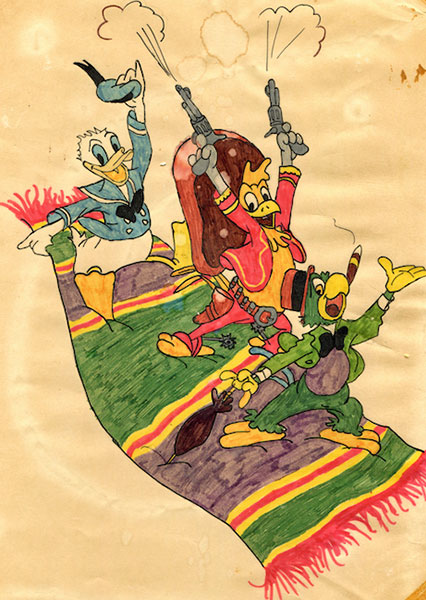

Walt Disney: The Art of Animation was checked out to Candice Farris dozens of times. I copied my favorite illustrations on typing paper, colored with new-at-the-time felt-tip markers. After graduation, I went to work in an office, but kept drawing Disney samples. In 1973, the lavish coffee-table book The Art of Walt Disney was published. Mine! I spent hours immersed in art and text, lingering long minutes over a watercolor of a bar of soap on a wooden counter, a study for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

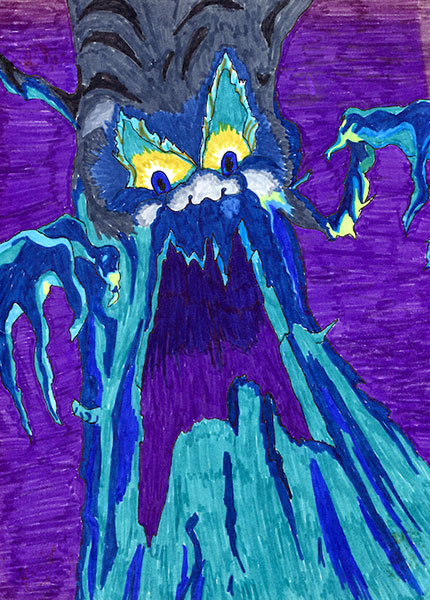

The bar of soap was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. Who would have thought soap could be so elegant, the wood grain so realistic I braced for splinters as I touched the paper. Suddenly I didn’t want to draw people — I wanted to paint homemade soap and carved headboards and scary trees! I copied the image of Snow White’s scary tree but lacked the sepias and grays for that lovely soap.

As time passed, I realized I could teach myself to write while holding down a fulltime job, but I needed art training to be good enough for Disney. My interest in Disney faded as my enthusiasm for children’s books grew. During moves, I lost my copy of The Art of Walt Disney. When books about Disney began cropping up in the 90s, The Art of Walt Disney was reprinted, two-thirds the original length, crowded with stingy images. I never forgot the watercolor soap and was delighted to find it included in the new edition. I own that book and many others about early Disney (anything after his death in 1966 doesn’t interest me).

Lately I’ve struggled to find a project to work on, finally settling on an idea more than four years old. I’d fleshed out the idea between other writing projects, but an element was missing. Magic. It’s not an area I’m comfortable with, as I’m not an imaginative writer. I could never think up Harry Potter or hobbits. As often when I’m stuck, I turn to a different creative source.

I spread my Disney books on the floor and read and looked. Walt Disney envisioned an orange grove as an amusement park, when such places were tawdry and tasteless, that would make people experience wonder. He envisioned animation as an art form, not just filler cartoons, but as full-blown stories.

Disney told his artists the story of Snow White, then urged them to reach the high standards it would take to make that vision a reality. The story had an evil queen, a poisoned apple, a talking mirror. To make the magic credible, scenes needed to be grounded in down-to-earth things. The homely dwarfs’ cottage in the woods with its hand-carved beds, crockery, and candlesticks offset the queen’s dark castle.

I studied the picture of the soap again. It’s still beautiful, but this time I saw its deeper truth. That humble soap enabled audiences to believe in the magic parts. If I keep in mind that magic grows from the ordinary, not the fantastic, from things people can associate themselves with, I can tackle my book.

My mentor won’t be Rowling or Tolkien, but a man who, at the age of nine, delivered newspapers at 3:30 a.m. in deep snow, stealing a few minutes to play with toys left out on porches because his father wouldn’t let him have any. Walt Disney grew up to give generations joy and unlimited dreams. Each day when I go to my computer, I’ll imagine him urging me to higher standards.