Outside my window right now: bare trees, gray sky, a brown bird. No, let’s try again. Outside my window, the leafless sweetgum shows a condo of squirrels’ nests, a dark blue rim on the horizon indicates wind moving in, and a white-crowned sparrow scritches under the feeders. Better. Even in winter, especially in winter, we need to wake up our lazy brains, reach for names that might be hibernating.

In November, I taught writing workshops at a school in a largely rural county. I was shocked to discover most students couldn’t name objects in their bedrooms, much less the surrounding countryside. Without specific details, writing is lifeless. More important, if children can’t call up words, can’t distinguish between things, they will remain locked in wintry indifference. Some blame falls on us.

A recent edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary swapped nature words for modern terms. Out went acorn, wren, dandelion, nectar, and otter. In went blog, bullet-point, attachment, chatroom, and voicemail. Updating dictionaries isn’t new. And maybe cygnet isn’t as relevant as database, but it’s certainly more musical. If we treat language like paper towels, it’s no wonder many kids can’t name common backyard birds.

A recent edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary swapped nature words for modern terms. Out went acorn, wren, dandelion, nectar, and otter. In went blog, bullet-point, attachment, chatroom, and voicemail. Updating dictionaries isn’t new. And maybe cygnet isn’t as relevant as database, but it’s certainly more musical. If we treat language like paper towels, it’s no wonder many kids can’t name common backyard birds.

When I was nine, my stepfather taught me the names of the trees in our woods, particularly the oaks. I learned to identify red, white, black, pin, post, and chestnut oaks by their bark, leaves, and acorns. Labeling trees, birds, and wildflowers didn’t give me a sense of ownership. Instead, I felt connected to the planet. I longed to know the names of rocks, but they kept quiet.

That same year we fourth graders were issued Thorndyke-Barnhart’s Junior Dictionary. I fell on mine like a duck on a June bug, enchanted by new words. My parlor trick was spelling antidisestablishmentarianism, the longest word in the dictionary. Kids can Google the longest word in the English language, but the experience isn’t the same as browsing through a big book of words.

Emerson wrote, “… the poet is the Namer, or Language-maker … The poets made all the words, naming things after their appearance, sometimes after their essence, and giving to every one its own name and not another’s.” I believe young children are poets, assigning names and making up words to mark new discoveries. After they become tethered to technology, they parrot words from commercials, programs, and video games. That fresh language is lost.

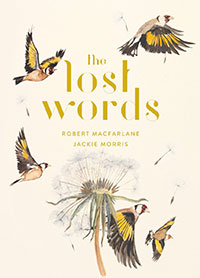

So imagine my delight when I found a new book for children, The Lost Words: A Spell Book. British nature-writer Robert MacFarlane paired with artist Jackie Morris to rescue 20 of the words snipped from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. Words like newt and kingfisher are showcased as “spells,” rather than straight definitions. MacFarlane’s spells let the essence of the creature sink deep, while Morris’s watercolors create their own magic.

So imagine my delight when I found a new book for children, The Lost Words: A Spell Book. British nature-writer Robert MacFarlane paired with artist Jackie Morris to rescue 20 of the words snipped from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. Words like newt and kingfisher are showcased as “spells,” rather than straight definitions. MacFarlane’s spells let the essence of the creature sink deep, while Morris’s watercolors create their own magic.

On their joint book tour throughout England, MacFarlane and Morris introduced children to words — and animals. On her blog Morris writes: “I was about to read the wren spell to a class of 32 six-year-olds when the booksellers stopped me. ‘Ask the children if they know what a wren is, first, Jackie.’ I did. Not one child knew that a wren is a bird. So they had never seen a wren, nor heard that sharp bright song. But now they know the name of it, the shape of it, so perhaps if one flits into sight they will see it, hear it, know it.”

The Lost Words makes me want to take children by the hand and tell them the names of the trees and birds and clouds that illustrate our winter landscape. By giving kids specific names, they can then spin a thread from themselves to the planet.

“Language is fossil poetry,” Emerson continues in his essay, “as the limestone of the continent consists of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, so language is made up of images, which now, in their secondary use, have long ceased to remind us of their poetic origin.”

Rock rasps, what are you?

I am Raven! Of the blue-black jacket and the boxer’s swagger,

Stronger and older than peak and than boulder, raps Raven in reply.

From The Lost Words

Let’s dig up lost words before they become buried beneath the rubble of STEM-worthy terms. Feel the shape of them, polish their shells, let them shine.

The older I get the more frequently my vocabulary shows it’s dwindling character. Now in my seventies, I miss all those words that remind me of my aging. Even sadder had I lived this life without their companionship. It’s a struggle to retrieve each word, or to acknowledge that struggle, but wonderful to find people who write books that help re-enrich that companionship, like The Lost Words, or The Writing Life, or Like Sound Through Water, or a thousand other lovelies.

Tom, you’ve sent *me* searching for Like Sound Through Water! I too am losing my vocabulary, the trees and birds I once knew so well I sometimes have to look up in guides. My regular language has become eroded by medication (and age) and I hunt for words I know are there, but elude me. So I’ll say the wrong word and hope the other person gives me the right one. The worst thing that can happen to a writer – losing words. I worry about the kids today who don’t have them to start with.

Loved this review! I had the privilege to be in Oxford when the writer/illustrator kicked off their tour. The book was showcased in every bookshop I entered. And just that fed my soul! Thanks for urging the rest of us writers to delve. ‑Michelle

P,S, Your first paragraph showing us how this can be done is marvelous! Thank you!!!

Michelle, you are very lucky! The book is considered the most beautiful book published in the UK in 2017. I immediately got it and the other books by Robert Macfarlane. How I wished I was there with you!

Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis (45 letters) … longest word. Today I discovered your info.

Inspired by your work. Thanks.