“The Boy chiefly dabbled in natural history and fairy-tales, and he just took them as they came, in a sandwichy sort of way, without making any distinctions; and really his course of reading strikes one as rather sensible.” The Reluctant Dragon

Kenneth Grahame wrote “The Reluctant Dragon” as a chapter in his book Dream Days, in 1898, ten years before publishing The Wind in the Willows. The Boy in the story is the son of a shepherd, during the time when dragons still needed slaying. Unlike most children of his station, Boy is a reader, spending “much of his time buried in big volumes.”

I was the Boy, lost in that wonderful stage where I read “to escape, to uncover … to find companionship … [to] set loose dreams,” as Pamela Paul and Maria Russo state in How to Raise a Reader. I plowed through novels and “factual” books. Visiting our tiny elementary school library was the high point of my week. We had no book lists. No one told us what we should be reading relative to study units. We were only required to check out a book, two at the most.

Classmates leafed through magazines or whispered to friends. For me, library period was serious business. Some kids couldn’t find a single book and Miss Sharp, the librarian, would pull one off the shelves. I knew those kids would return their books unread the next week. Why couldn’t I have their check-out allotments instead of agonizing between three books, one of which I’d have to slide behind the stacks so no one else would check it out. I habitually chose a novel and a science book and read them in a sandwichy sort of way.

In his introduction to A Hundred Fables of Aesop, published in 1899, Grahame wrote:

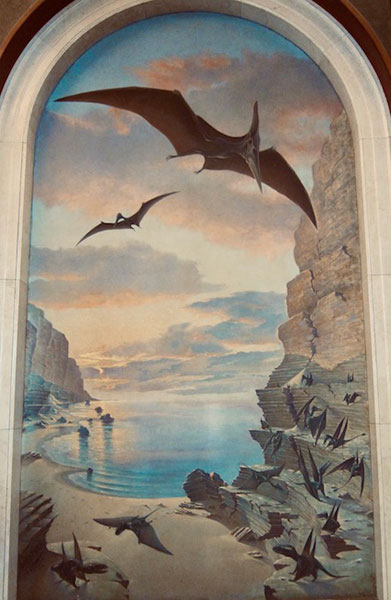

Vitality — that is the test; and, whatever its components, mere truth is not necessarily one of them. A dragon, for instance, is a more enduring animal than a pterodactyl. I have never yet met anyone who really believed in a pterodactyl, but every honest person believes in dragons — down in the back-kitchens of his consciousness.

I didn’t know yet about pterodactyls, but I did learn about the world’s first bird, Archaeopteryx, in All About Birds. At nine, I wasn’t sure about dragons since there weren’t any in Virginia, but this Jurassic Age creature, discovered in Germany in 1861, seemed very real. The illustration of its fossil remains rendered vitality in every line. I loved reading how the flying reptile developed, bone by bone, muscle by muscle, into today’s modern birds. I repeated softly the word Archaeopteryx to myself, loving the sound of it.

The borrower’s card in the pocket of All About Birds bore my signature every other line, I checked it out so many times. The only bird book I owned was a small Golden Nature Guide. Birds made no mention of archaeopteryx or pterodactyls, but it set loose dreams of my becoming an ornithologist.

The borrower’s card in the pocket of All About Birds bore my signature every other line, I checked it out so many times. The only bird book I owned was a small Golden Nature Guide. Birds made no mention of archaeopteryx or pterodactyls, but it set loose dreams of my becoming an ornithologist.

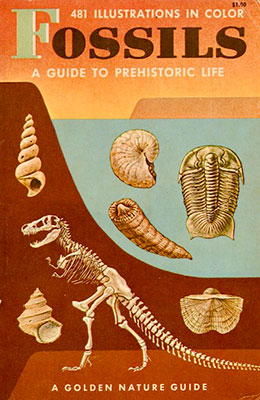

Across the Atlantic, in Scotland, seven-year-old Michael J. Benton received a Golden Nature Guide called Fossils. Four years younger than me, Michael pored over the pictures (“481 Illustrations in Color”). Fossils covered ancient life from cockroaches to corals, including Archaeopteryx and the astonishing Pteranodon, with its 25-foot wingspan. Michael was hooked:

“What excited me [about Fossils] was that the illustrations were all in colour — unusual still in the 1960s — and there were not only pictures of fossils, but reconstructions too. The text reflected the knowledge of the time — this is what Tyrannosaurs looked like, based on the classic studies by Professor Henry Osborn of the American Museum of Natural History, and this is how the dinosaurs died out, rather slowly, and perhaps as a result of long-term cooling climates (or maybe because they were too stupid to adapt to a changing world) … Nonetheless, as a seven-year-old, that was all I needed. It never entered my head to question the authority of something written in a book …”

Benton’s early interest in dinosaurs led him to study paleobiology. Now a professor at Bristol University, Benton is a world-renowned paleontologist and author, with a dinosaur named in his honor. Despite growing up in a country stuffed with stories of dragons, fairies, water horses, and other mythical creatures, his dream was let loose by a 1.00 (in American currency) children’s field guide.

Benton’s early interest in dinosaurs led him to study paleobiology. Now a professor at Bristol University, Benton is a world-renowned paleontologist and author, with a dinosaur named in his honor. Despite growing up in a country stuffed with stories of dragons, fairies, water horses, and other mythical creatures, his dream was let loose by a 1.00 (in American currency) children’s field guide.

I didn’t become a scientist, after all. My sensible, sandwichy method of reading — novels and nonfiction — sent me down a different road. I became a writer of fiction and nonfiction, though much of my fiction depends on research. In the back-kitchen of my mind, there are griffins and grackles. Both are vital, and both get along just fine.

the American Museum of Natural History in New York