On the day we learned my husband had stage 4 cancer, I stopped reading. For me, this is akin to stopping breathing. I read all the time, everywhere, even in the movie theater. Our house is filled with books. Tented novels sprawl by the bathtub, nonfiction sits in the dish drainer, all waiting for me to pick up and read a bit more as I pass through that room. Naturally I dip into one or two books in bed. But that night I did not read. I couldn’t.

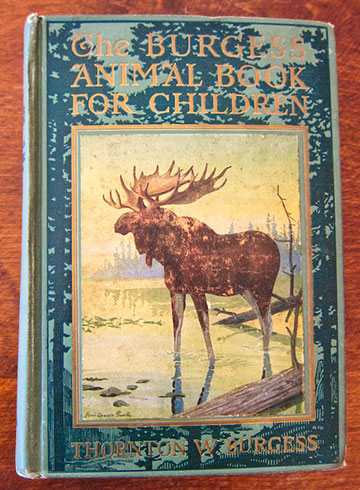

I went to the library, ventured into Barnes and Noble, came out empty-handed and bereft. After a few nights trying to sleep with every nerve outside my skin, I padded into my sitting room. There I keep the books most precious to me. I pulled off the shelf a one-hundred-year-old edition of The Burgess Animal Book for Children by Thornton W. Burgess and took it to bed. The rolled edges of the worn binding felt reassuring in my hands, the thick rag pages soft and gently foxed. Why turn to an ancient children’s book?

Because I didn’t have the energy for slick modern fiction. What comfort would I find flicking through some genre-bending novel? And because I’d read this book dozens of times as a kid.

It was most often the weekend book I’d check out on Friday, library day, in fifth grade. We were only allowed to take out two books a week. I’d choose a mystery or something about stars, with The Burgess Animal Book as my second choice. At home, I toted Burgess into our woods, perched on my favorite log, and read until dusk called me in.

The book, fictionalized stories laced with true facts, uses a frame device: a school run by Old Mother Nature to teach the animals of the Green Forest, the Old Briar-Patch, and the Green Meadows about their relatives. Her first students are Peter Rabbit and Jumper the Hare. Mother Nature tells them about Peter’s relative, the marsh hare. She also asks Peter and Jumper to describe themselves and they learn how they are alike yet different.

As the book progresses, the class expands to many students and the lessons include most mammals in North America, relative by relative. In his introduction, Burgess states: “Only through intimate acquaintance may understanding of the animals in their relations to each other and to man be attained. I offer [this book] … hopeful that it will prove of some value in acquainting children with their friends and mine — the animals of field and woods, of mountain and desert, in the truest sense the first citizens of America.”

Burgess’s style is unapologetically old-fashioned:

Hardly had jolly, round, red Mr. Sun thrown off his rosy blankets and begun his daily climb up in the blue, blue sky when Peter Rabbit and his cousin, Jumper the Hare, arrived at the place in the Green Forest where Peter had found Old Mother Nature the day before. She was waiting for them, reading to begin the first lesson.

Why, you might be wondering, would a progressive Fairfax County school keep such a dated book on their shelves in the 1960s? I don’t know but I’m glad they did. While Burgess’s prose can be flowery — Peter Rabbit runs lipperty-lipperty-lip — Old Mother Nature’s teachings are delivered concisely and accurately, and she often gives her students questions to ponder.

This book taught me about animals. I looked up from the page to observe squirrels tussling high in trees, followed rabbit trails through brambles, noted raccoon pawprints along the muddy creek. As a lonely child with no close neighbors and few friends at school, The Burgess Animal Book for Children showed me how to grow into my true self, a woodland creature.

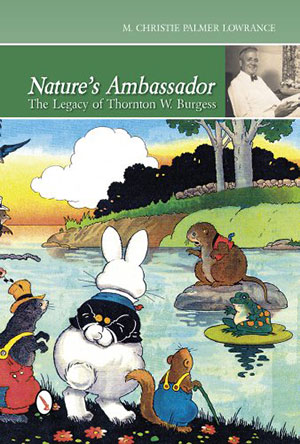

In Nature’s Ambassador: The Legacy of Thornton W. Burgess by Christie Palmer Lowrance, I learned Burgess wrote 170 wildlife and nature books, beginning with Old Mother West Wind in 1910. He wrote thousands of stories and articles for children and educators, including a daily newspaper column, “Bedtime Stories,” from 1912 to 1960. A monthly magazine series spawned the Green Meadow Club, where members pledged to protect wildlife. The club sponsored drives for bird sanctuaries resulting in millions of acres set aside. Burgess gave children autonomy in conservation before the end of World War I. His Radio Nature League series was broadcast in 30 states. In 1960, at the age of 86, he published his 15,000th newspaper column.

In Nature’s Ambassador: The Legacy of Thornton W. Burgess by Christie Palmer Lowrance, I learned Burgess wrote 170 wildlife and nature books, beginning with Old Mother West Wind in 1910. He wrote thousands of stories and articles for children and educators, including a daily newspaper column, “Bedtime Stories,” from 1912 to 1960. A monthly magazine series spawned the Green Meadow Club, where members pledged to protect wildlife. The club sponsored drives for bird sanctuaries resulting in millions of acres set aside. Burgess gave children autonomy in conservation before the end of World War I. His Radio Nature League series was broadcast in 30 states. In 1960, at the age of 86, he published his 15,000th newspaper column.

Burgess didn’t just write. He grew up on Cape Cod, in the cranberry bogs and the marshes and later, the woods near Sandwich. He knew famous naturalists of the day: ornithologist Frank Chapman, who started the Christmas Bird Count, zoologist and conservationist Frank Hornaday, who helped save bison. Burgess and ornithologist Alfred Gross banded the last heath hen and let him go free, into extinction, unlike the last passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet, birds that had died in zoos.

That night, tucked in bed with The Burgess Animal Book for Children, I studied the dedication: “To the cause of wild life in America, especially the mammals many of which are seriously threatened with extinction, this book is dedicated.” Written in 1920, reread by me on the 100th anniversary year of Thornton W. Burgess’s birth.

The old-fashioned language soothed me. My nerves sank beneath my skin. I remembered every one of Louis Agassiz Fuertes’ six dozen illustrations, painted in clear but muted hues, unlike the over-saturated art in many modern children’s books. Before I fell asleep, somewhere between the stories of Thunderfoot, Fleetfoot, and Longcoat, I longed to be in Old Mother Nature’s school. I wished I had been enrolled in the Green Meadow Club, had pledged to learn about wildlife and protect animals. Then I realized that, because of a childhood book, I had always done so.

This year, which promises to be troubling in many arenas, my projected writing projects will be about animals. Thank you, Thornton W. Burgess.

Loved this!! I first came to the Burgess stories in the New York Herald Tribune, a New York City daily. Every day they published one chapter of a serialized Burgess animal story, along with an illustration by Harrison Cady. I have no idea as to the age I came to these but I must have been fairly young. Even though I was a city boy I devoured these woodland stories. When, in a neighborhood used bookstore – way back in the dim and dusty back – I discovered I could buy Blackie The Crow, Lightfoot the Deer, and many of the other Burgess books in Grosset & Dunlap volumes for 25 cents each I began to collect… Read more »

Dear Avi, thank you so much for your kind response. I would have been thrilled to have read Burgess’s stories in a newspaper! Over the years, I’ve collected anything Burgess I could find, including his autobiography. I have BLACKY THE CROW, a well-read first edition with the inscription “Miss Helen Withers, July 19th 1922, from “Gramp.” Burgess wrote many books in different series, Green Meadow, Mother West Wind, Wishing-Stone, etc. I can’t imagine being so prolific! I too moved on to Freddy the Pig. But as you so eloquently stated, Burgess led me to deeper reading (I learned on comic books) and the importance of incorporating fact… Read more »

As a child in western Massachusetts we were treated once per year or so to a visit to the Laughing Brook Nature Sanctuary where a kindly woman dressed as Old Mother West Wind welcomed children and told stories. There was a variety of animals to visit as well, most being rehabilitated from an accident or injury. Built on the site of Burgess’ home, it was a magical spot for families and nature appreciation. Sadly it later fell into decline due to mismanagement and other factors, but I really treasured those visits to see the creatures that lived so vividly in the pages of his stories!

Oh, you lucky child! I’ve read about the Laughing Brook Nature Sanctuary and had hoped to go sometime (from Virginia!), but by the time I found out about it, it was over. Thank you for sharing your memory! Candice