Knee-deep in spring! The rabbits will be here soon, rangy after a long winter. They like our yard because we have low bushes good for hiding and we let the lawn go to clover and dandelions. I like to think rabbits feel safe because they have little chance elsewhere. If ever there was an animal with “a thousand enemies,” it’s the cottontail rabbit, a creature I never paid much attention to until Watership Down.

Knee-deep in spring! The rabbits will be here soon, rangy after a long winter. They like our yard because we have low bushes good for hiding and we let the lawn go to clover and dandelions. I like to think rabbits feel safe because they have little chance elsewhere. If ever there was an animal with “a thousand enemies,” it’s the cottontail rabbit, a creature I never paid much attention to until Watership Down.

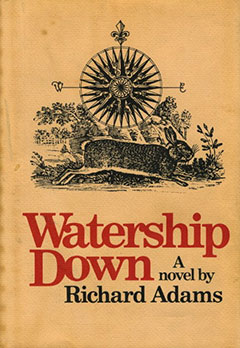

I found Watership Down in 1974. I was twenty-two, still in the thrall of The Lord of the Rings and The Once and Future King yet feeling jaded that the world was nothing like Middle-earth or Gramerye. One day on my lunch hour, I walked into Woodward & Lothrop to browse the book department. On display were stacks of a new novel with a compass rose and a rabbit on the cover. It was thick — over 400 pages — British, and a fantasy. The hardcover cost $6.95, a fortune on my secretary’s salary, but I bought it. At work I kept the book on my knees, sliding out from my desk to sneak-read when no one was looking.

With the first foreboding sentence, “The primroses were over,” I knew this was not a story about bunnies. It was darker, sharper, and exactly what I needed. At that time, my life seemed all edges and uncertainty. I felt a lot like Fiver, the nervous “outskirter” (in the hierarchy of Adams’ rabbits, outskirters lacked aristocratic parentage, weight, and strength). I wanted to write for children, but, more than two years out of high school, couldn’t seem to move forward. Was I doomed to type other people’s words forever?

I learned that the author, Richard Adams, worked for the civil service and didn’t start writing until he was fifty. Watership Down began as a tale he told his daughters on a drive to Stratford-on-Avon. They urged him to write the story — it took two years. After fourteen rejections, a small publisher printed 2500 copies. The book became an instant classic, allowing Richard Adams to quit his job and write full-time.

I learned that the author, Richard Adams, worked for the civil service and didn’t start writing until he was fifty. Watership Down began as a tale he told his daughters on a drive to Stratford-on-Avon. They urged him to write the story — it took two years. After fourteen rejections, a small publisher printed 2500 copies. The book became an instant classic, allowing Richard Adams to quit his job and write full-time.

The book won the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize. A reviewer for The Economist declared, “If there is no place for Watership Down in children’s bookshops, then children’s literature is dead.” I’ve never felt it is a children’s book, but that could be because I came to it as an adult. Adams himself refused to pin down the book’s intended audience: “What age-group is it aimed at?” someone would ask. “I don’t aim it, madam. It just goes off by itself.”

Adams credits Ronald Lockley’s The Private Life of the Rabbit for natural history details, but in aiming for the truth in his story, he drew upon his childhood love of Walter de la Mare’s poetry, especially “The Children of Stare”:

‘Tis strange to see young children

In such a wintry house;

Like rabbits’ on the frozen snow

Their telltale footprints go.

His reaction to the poem: “Cold, ghosts, grief, pain and loss stand all about the little cocoon of bright warmth, which is everywhere pierced by a wild, numinous beauty, catalyst of fear and weeping.” The poem was far from comforting, but it told the truth, and led Adams to tackle “the really unanswerable things” in Watership Down, which is also about grief, pain, and loss, while everywhere pierced by a wild, numinous beauty.

Watership Down changed my life (the last book to do so). I never saw rabbits — or the natural world — the same way again. I turned to the works of Rachel Carson and Hal Borland.

I took notice of the environment. And I watched rabbits during evening silflay, Lapine for feeding above-ground.

Rabbits kept me grounded to the planet. I bought rabbit garden statuary, rabbit figurines and paintings. A framed poster of Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait’s Rabbits on a Log hangs in our bathroom. The porch is inhabited by rabbits, and each spring I buy new pieces of rabbit-themed china.

In 1978, before we were married, my fiancé and I saw the beautifully-animated (and not for kids) movie. When Art Garfunkel began singing “Bright Eyes” at the death of main character Hazel, I cried so hard my fiancé almost called an ambulance (yet still married me). I still haven’t gotten over it.

Richard Adams gave me rabbits, but he also gave me direction. I decided to get a move on with my career. Instead of shopping on my lunch hour, I went to the library, staked out a table in the children’s room, and wrote stories. My first children’s magazine sale came from a lunch time work session.

Most of all, Richard Adams gave me humanity. Through his band of small, ordinary animals facing homelessness and survival, I saw myself, also small and ordinary, as a storytelling animal. I give mysteries, fantasy, historical fiction, biographies, and contemporary tales to children. One day, those readers will tell their own stories. Maybe even about rabbits.

Oh, this is such a lovely essay, Candice! My husband, Randy, is a huge Watership Down fan, and he introduced me to the book, movie, and “Bright Eyes” (yes, heartbreaking!).

Candice, so that’s how you starting writing. I didn’t know that. I have also shopped in “Woodies”.

Debra Downing