In the fifth grade, my best friend and I discovered a tangle of honeysuckle in the scrubby woods bordering our school playground. It would make the perfect recess refuge. All we had to do was pull the honeysuckle from inside the circle of saplings it was twined around, leaving a curtain of vines.

In the fifth grade, my best friend and I discovered a tangle of honeysuckle in the scrubby woods bordering our school playground. It would make the perfect recess refuge. All we had to do was pull the honeysuckle from inside the circle of saplings it was twined around, leaving a curtain of vines.

The next day, we sprinted into the thicket and began ripping out vines. Honeysuckle, we learned, often grows with poison ivy. When we were no longer coated in calamine lotion, we finished our hideout. Each recess, we dashed down the hill when the teacher wasn’t looking and zipped into Honeysuckle Hideout. Having a secret place at school, where we were corralled by adults, gave us an exhilarating sense of freedom.

Until the day three sixth graders invaded our Hideout. The presence of sneering, older girls shattered our privacy. Our haven suddenly seemed childish and the power we’d felt spying on others diminished in an instant. We were back in the general population of ordinary kids.

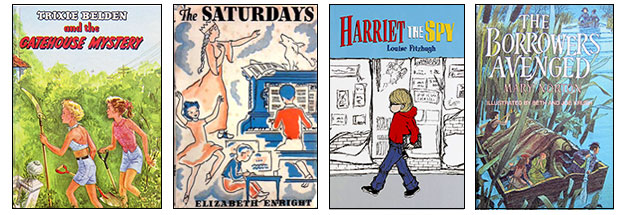

Although I had my own room at home, I made a den from a blanket-covered card table, cobbled a makeshift playhouse inside my closet, and claimed the nook behind the furnace in our basement. In these places I felt safe and secluded. The books I read fueled the need for secrecy: the gatehouse-turned-clubhouse in the Trixie Belden mysteries, the Melendy siblings’ Office in The Saturdays, the dumbwaiter Harriet the Spy squeezed into, the Borrowers’ realm beneath the floorboards.

Once, I spread a tarp inside a roll of unused chicken wire sitting along one side of our garden. I crawled inside. Ragweed and tall grass cloaked the fence roll from view. The tarp floor smelled musty. I tucked a box of Milk Duds and my library book in a fold at one end. The cat joined me. We whiled away summer afternoons as bumblebees drowsed in the clover and a thrush sang sweetly deep in the woods.

I didn’t know then that place-making helped connect me to the planet. Quiet and hidden, I began to understand I was part of the larger space shared by the bumblebees, the thrush, and the cat. I continued to create these sanctuaries no matter where I lived. As poet Kim Stafford said in his essay, “A Separate Hearth:” I would take any refuge from the thoroughfare of plain living … there I pledged allegiance to what I knew, as opposed to what was common.

The geography of our pasts is littered with snow forts and retreats beneath rhododendron bushes, tree houses and havens under front porches. Secret spaces, no matter how tiny or crude, expand to accommodate kids’ fantasies and imagination. Children’s den-making, says Colin Ward in The Child in the City, carries over into adulthood. “Behind all our purposive activities, our domestic world, is this ideal landscape we acquired in childhood.” I still carve out sanctuaries to escape dishes and laundry and, nowadays, the invasion of email.

In my 1920s themed sitting room, the smallest room in our house, I sit on the floor surrounded by vintage children’s books, old perfume bottles, and McCoy violet pots filled with colored pencils. I write notes using my grandfather’s cedar chest as a desk, read, or work on art projects. Each evening, I wind down in this cozy room and let the day waft out the window.

Where do today’s children craft their private spaces? I never see kids in my neighborhood building forts or playhouses or even sitting under a tree. As Elizabeth Goodenough says in her book, Secret Spaces of Childhood, “Without a corner to build a world apart, [children] can’t plant what [author] Diane Ackerman calls ‘the small crop of self.’”

Where do today’s children craft their private spaces? I never see kids in my neighborhood building forts or playhouses or even sitting under a tree. As Elizabeth Goodenough says in her book, Secret Spaces of Childhood, “Without a corner to build a world apart, [children] can’t plant what [author] Diane Ackerman calls ‘the small crop of self.’”

Many kids escape adults in their bedrooms, holed up with laptops or Play Stations. Apps and games let children create marvelous kingdoms. A house made of sticks can hardly compete with, say, the sophistication of Fortnite’s “Loot Lake.” Yet a space of the child’s own making provides solitude and expands to accommodate fantasies and imagination. Secret places in games are bounded by adult-created rules, the product of someone else’s imagination. Those seemingly limitless options are contained in a box.

How will children find their place in the world in front of screens? Hands tapping plastic keys can’t feel the fiber toughness of honeysuckle vines or the rough surface of a sun-warmed tarp. Eyes focusing on flickering avatars can’t track the up-and-down flight of a bluebird. The player’s sense of identity, disguised in a “skin,” is merely a reflection in the glass.

Better to seed that small crop of self with books which give a child ideas, words that flourish into mental pictures, and send her out the door to build her own private kingdoms.

I love this! Excellent read and so. very. true. Creativity and secret hiding places are unfortunately a thing of the past. Our children today don’t know what they’re missing. Many thanks for sharing!