When the director of Hollins University’s graduate program in children’s literature asked me to teach a critical class on the history of children’s book illustrators, I said no. Even with an MFA in writing for children from Vermont College, an MA in children’s literature from Hollins, scores of published books, and years of teaching graduate-level creative classes, I still felt like a fraud. Someday I’d be called out because I never got an undergraduate degree or understood what “dialogic” meant. But the director insisted I was the only one who could teach this course, required for students in the new MFA Writing and Illustrating Children’s Books program.

Maybe … When I was nineteen, I bought a children’s literature textbook at a yard sale. That one-dollar book became the first in my children’s literature library, with a heavy concentration in illustrators. What I lacked in academic experience, I could make up for in passion. As a kid, I longed to be an illustrator, switching to animation when I was a teenager. Those dreams never transpired, but my love for art stayed true.

Once home from that summer of teaching, I gathered my books on illustration. The floor nearly fell in! I had so much material, I didn’t need to leave my house. The course would begin with the earliest children’s book illustrators, up to the end of the twentieth century. Hollins summer residence terms are six weeks, two classes a week, each class three hours.

I would cover the early illustrators in the first class, then spend the rest of the term highlighting technique, printing methods, and ground-breaking artists. My outline looked deadly. I tossed it and any pretension I had of being a “real” academic. I’d teach the class the way I wish someone would have taught me — moving chronologically through time, giving backgrounds of illustrators, and, most important, telling stories along with showing the art. Students would get plenty of information, but they would also have a sense of the artists’ lives.

The outcome for the students? Rather than turn them into walking encyclopedias, I wanted them to fall in love. Fall for one illustrator, one artist that would change their lives, change the way they made their own art.

I began scanning illustrations for PowerPoint presentations. My little flatbed scanner hummed day after day until I had 1000 slides. A thousand! Even spread out over twelve classes, a thousand slides would send students flying for the exit. I cut and cut, until I had 500 slides. Well, they’d get their money’s worth.

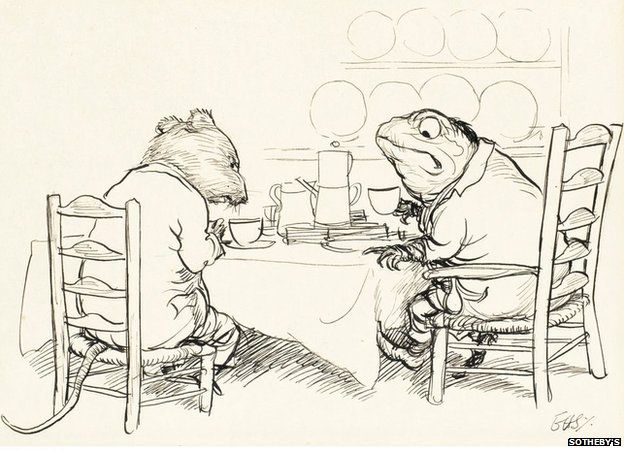

On the first day of our class, I told the students to buckle up, their first lecture would be like a motorcycle ride through the Louvre. We covered 150 years of illustration, from the 1830s (George Cruikshank) to the 1930s (E.H. Shepard), criss-crossing between England and America. There were 75 slides, my script was 35 pages. Amazingly, they all came back for the next class.

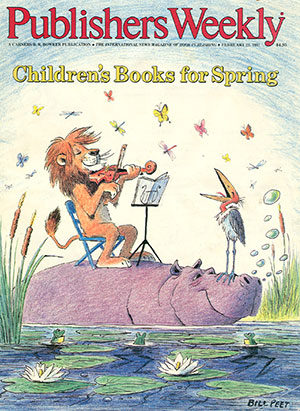

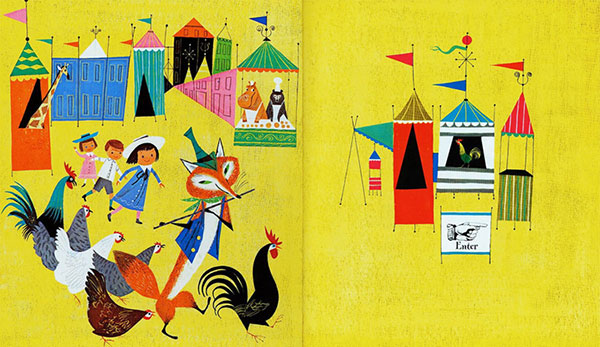

Halfway through the term, I added another facet to the unit on mid-century illustrators. Artists who’d started at Disney Studios and gone on to produce children’s books — people like Bill Peet, the Provensens, and Gyo Fujikawa. Twelve classes was not enough! So, I created a thirteenth class, something no one had ever done before. Working around students’ schedules, we met during lunch. I opened the lecture up to everyone in our program. After that, other faculty members began holding lunchtime lectures.

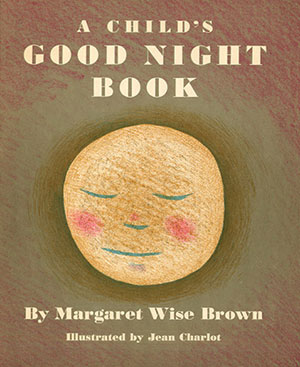

Instead of a single text, students were required to discuss ten picture books I’d selected. Many had never seen Robert Lawson’s technically brilliant line-work for Ferdinand the Bull. They all knew Clement Hurd’s art for Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon but had missed Jean Charlot’s masterful pastels in A Child’s Good Night Book. Although I’d put together a zillion slides, I staggered into each class with more examples of the featured artist’s work. Slides are great, but nothing beats paging through actual books, most vintage or hard-to-find.

We had “special” days, such as sampling every black form of media I could lay my hands on for students to emulate Wanda Gag’s printer’s black. We ate blueberry Danish during the Robert McCloskey class. Students tore pieces of colored paper and made Leo Lionni-style collages as we discussed Little Blue and Little Yellow.

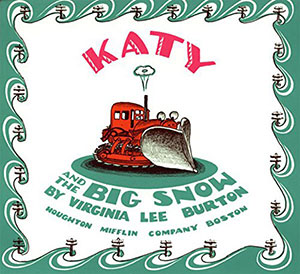

Students began bringing in books from mad-dash trips home to share. They showed sketches in the style of Virginia Lee Burton or Donald Crews. And they did what I hoped — they fell in love.

After my initial run, I repeated the course every other year. Students proclaimed it was their very favorite class in the program. On the last day of the term, we traditionally eat Krispy Kreme donuts and I ask the students who they fell in love with during the term. Often, it’s more than one illustrator. Then there are hugs and heartfelt goodbyes, even a few tears.

Summer 2018 was the final time I taught that lovely course. After thirteen years at Hollins, I needed to spend summers home for personal reasons. Instead I’ll teach intensives at the university, as I have — and will continue to do — for other programs and organizations. As it turned out, my students changed my life, and teaching became my passion.

On the last day of my last illustration class, I gathered my materials one last time, looked around at the empty classroom where’d I’d taught so many years, and turned out the light. The tears were mine.

Oh my, what a treasury! Those students were incredibly lucky to learn from such a passionate teacher.