Recently I attended a writer’s conference mainly to hear one speaker. His award-winning books remind me that the very best writing is found in children’s literature. When he delivered the keynote, I jotted down bits of his sparkling wisdom.

At one point he said that we live in a broken world, but one that’s also filled with beauty. My pen slowed. Something about those words bothered me. The crux of his speech was that as writers for children, we are tasked to be honest and not withhold the truth.

After the applause pattered away, the air in the ballroom seemed charged. Everyone was eager to march, unfurling the banner of truth for young readers! If we had been given paper, we would have started brilliant, authentic novels on the spot.

The keynote’s message carried over into break-out sessions. Panelists admitted to craving the truth when they were kids, things parents wouldn’t tell them. Participants agreed. We should show kids the world as it really is! The implication being that children leading “normal” lives should be aware of harsher realities and develop empathy. Kids living outside the pale would find themselves, maybe learn how to cope with their situations.

I stopped taking notes.

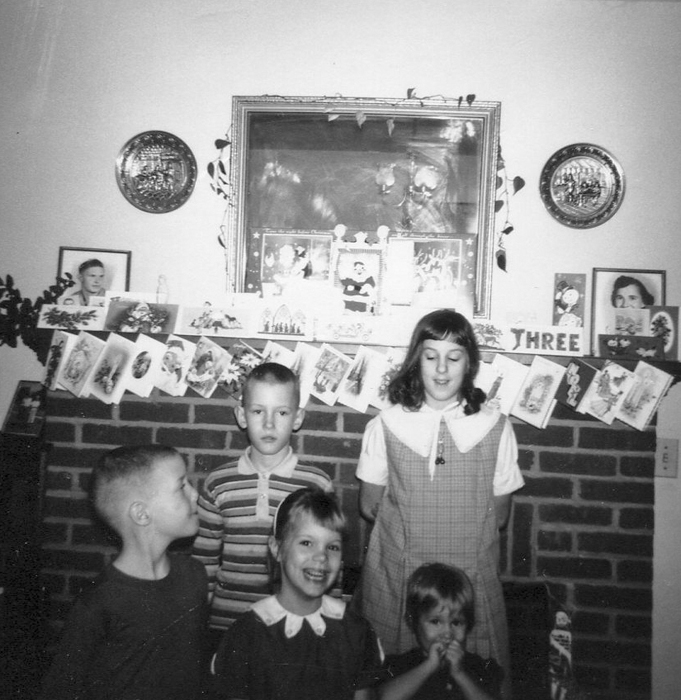

Here’s my truth: I was born into a broken world. By age four, I’d experienced scores of harsher realities. At seven, I learned the hardest truth of all: that parents aren’t required to want or love their children. I spent most of my childhood fielding one real-world challenge after the other. I did not want to read about them, though few books fifty years ago explored issues of alcoholism, homelessness, and domestic violence.

I read to escape, delving into stories where the character’s biggest challenge was finding grandmother’s hidden jewels, as in The Secret of the Stone Griffins. Fluff? So what? In order to set the bar, I had to seek normal and didn’t care if Dick-and-Jane families weren’t real. Even Mo, the alien girl in Henry Winterfield’s Star Girl who’d tumbled from her spaceship, lived a normal life with her family on Asra, climbing trees on that faraway planet like I did on Earth.

I read to escape, delving into stories where the character’s biggest challenge was finding grandmother’s hidden jewels, as in The Secret of the Stone Griffins. Fluff? So what? In order to set the bar, I had to seek normal and didn’t care if Dick-and-Jane families weren’t real. Even Mo, the alien girl in Henry Winterfield’s Star Girl who’d tumbled from her spaceship, lived a normal life with her family on Asra, climbing trees on that faraway planet like I did on Earth.

In a family of non-readers, I broke free of the norm. Not only did I read constantly, but decided to be a writer at an early age. I’d write the kind of books I loved, books where secrets involved buried treasure, not things I had to keep quiet about; books where kids felt protected enough to embark on adventures.

My mother and stepfather regarded me with odd respect, as if unsure what planet this kid had come from. So long as “story-writing” didn’t interfere with schoolwork (it did), my mother excused me from chores. Only once did she declare reading material inappropriate.

I was nine and fresh out of library books. I found a True Story magazine and was deep into story about an abused boy when my mother caught me. She thought I was learning about sex. I was outraged by the injustice: punished for reading about a kid my age! Now I think about the irony.

Then I grew up and wrote children’s books. Most of my fiction was light and humorous. Yet some brave writers tackled serious subjects. My colleague Brenda Seabrooke wrote a slender, elegant verse novel called Judy Scuppernong. This coming-of-age story touches on family secrets and alcoholism. The format was perfect for navigating difficult subjects.

Then I grew up and wrote children’s books. Most of my fiction was light and humorous. Yet some brave writers tackled serious subjects. My colleague Brenda Seabrooke wrote a slender, elegant verse novel called Judy Scuppernong. This coming-of-age story touches on family secrets and alcoholism. The format was perfect for navigating difficult subjects.

I sat down and wrote a poem called “Nobody’s Child.” More followed, until I’d told my own story. My agent submitted my book Nobody’s Child. One editor asked me to rewrite it as a YA novel. “You’ve already done the hard part,” he said. He was wrong. Each time I revised (many times over the years), I had to crawl back into that dark place. Some people said that by telling my story, I’d be able to put it behind me. They were wrong. I never will.

The truth is, I wrote Nobody’s Child to find answers. I already knew the what and the how. I wanted to know why. But by then everyone involved was gone, taking their reasons with them. If I were to fictionalize my story to help another child in the same situation, I couldn’t make the ending turn out any better.

In the fantasies and mysteries and books about animals I read as a kid, I figured out I’d probably be okay. When I looked up from whatever library book I was reading, or whatever story I was writing, I noticed the real world around me. Not all of it was broken. There were woods and gardens and cats and birds and, yes, at last, people who cared about me.

Author Peter Altenberg said, “I never expected to hold the great mirror of truth up before the world; I dreamed only of being a little pocket mirror …one that reflects small blemishes, and some great beauties, when held close enough to the heart.”

Author Peter Altenberg said, “I never expected to hold the great mirror of truth up before the world; I dreamed only of being a little pocket mirror …one that reflects small blemishes, and some great beauties, when held close enough to the heart.”

Valiant children’s writers will flash the great mirror of truth in bolder works than mine. I’m content to shine my little pocket mirror at small truths, no bigger than a starling’s sharp eye, from my heart to my reader’s.

As usual, lovely and important words here in Big Green Pocketbook. Thank you.

Thanks, Melanie. As usual, high praise coming from you!

I’m so glad I took the time to read this post – thanks, Candace, for writing it. I’ve admired your books for a long time! I also made a delightful discovery here: I found Brenda Seabrooke’s JUDY SCUPPERNONG at a tiny book shop on the island of Bermuda in the summer of 1997. It was the first novel/ novella in verse that I’d ever read and I believe it planted the seed of possibility for my own writing in that form several years later. I haven’t thought about that book for quite some time and now I’m going to try and dig out my copy.

Jen, I’m such a fan! I teach your books in my nonfiction writing class and can’t wait to read your latest. I believe Brenda’s book was *the* first verse novel for young people. She also wrote a sequel, Under the Pear Tree (I think). I re-read Brenda’s book at least once a year.

I couldn’t agree more, Candace. And what I especially liked is that “escaping” doesn’t mean reading only humor, nor reading only high fantasy — your article not only reminds us of the breadth of language and story, but the necessity of recognizing the diversity of readers’ needs and experiences. And now I’m going to look for JUDY SCUPPERNONG! I thought I’d read every verse novel written.

Lots of kids escape into nonfiction – I did that, too. Books took me to places and they still do. Do search for Judy Scuppernong – it was probably the first verse novel for kids. It’s so elegant and lyrical, most likely a model for many writing in that format. Thanks for commenting!

The small truths in your stories glitter like an eagle’s eye! Bigger than a starling’s! Kids need and deserve many perspectives in the books they read.