Not all alphabet books are for the purpose of early literacy, nor do they meet the criteria for traditional alphabet books such as containing upper and lower case letters, clean typefaces, and clearly identifiable objects. Some alphabet books tell a sequential story. Others are a potpourri of objects with no connection. Still others are thematically connected, as are the following two sets of Caldecott Honor ABC books.

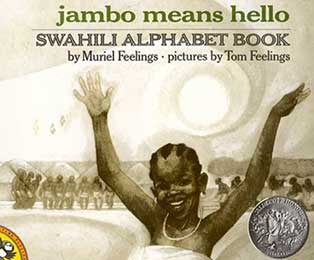

The first theme is African culture. In 1975, Jambo Means Hello: Swahili Alphabet Book won the Caldecott Honor. Written by Muriel Feelings and illustrated by her husband Tom Feelings, they chose the Swahili alphabet because this language is “spoken across more of Africa than any other language.” It is the official language of the African Union, and its official name is Kiswahili. However, for simplicity’s sake, Feelings refers to the language as Swahili (Feelings, 1974, Introduction). It is spoken by over 200 million people and is one of the world’s ten most spoken languages. Though this book is almost fifty years old, the importance of the language was recently recognized by the United Nations when they declared July 7, 2022, as World Kiswahili Day (UNESCO, 2022).

The first theme is African culture. In 1975, Jambo Means Hello: Swahili Alphabet Book won the Caldecott Honor. Written by Muriel Feelings and illustrated by her husband Tom Feelings, they chose the Swahili alphabet because this language is “spoken across more of Africa than any other language.” It is the official language of the African Union, and its official name is Kiswahili. However, for simplicity’s sake, Feelings refers to the language as Swahili (Feelings, 1974, Introduction). It is spoken by over 200 million people and is one of the world’s ten most spoken languages. Though this book is almost fifty years old, the importance of the language was recently recognized by the United Nations when they declared July 7, 2022, as World Kiswahili Day (UNESCO, 2022).

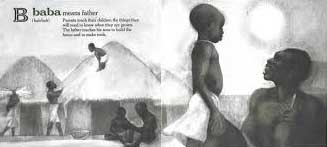

The Kiswahili language does not contain the letters Q or X, so the remaining 24 letters of the alphabet feature words about people, customs, and activities of Central and East African countries on double page spreads. Each word, its pronunciation, and meaning, is followed by a one or two sentence explanation.

The illustrations extend the meaning of the words and provide context. Feelings uses black ink, white tempera, and linseed oil on textured board. A detailed description of his process is provided in “A Note about the Art” in the back of the book. In reproducing the art, it is photographed twice using a method called double-dot. The first photograph includes all the art and is printed in black ink. The second photograph includes only part of the art and is printed in the color ochre, a sort of brownish-tan clay color. “The second color is not obvious in the final book, but has the effect of enriching the reproduction and maintaining the strength, subtlety, and warmth of the original art” (Feelings, 1974, A Note about the Art). The only other colors in the book are brown in the African map showing the countries where Kiswahili is spoken and green letters of the featured alphabet word.

Both Feelings have lived and traveled extensively in Africa, lending authenticity to the illustrations. It is their hope that this book, and their 1970 Caldecott Honor book Mojo Means One: Swahili Counting Book, would encourage children of African descent to learn more about their ancestry. As Muriel Feelings states in her introduction, “With new words come new ideas and an understanding of the people and environment which created the language” (Feelings, 1974, Introduction).

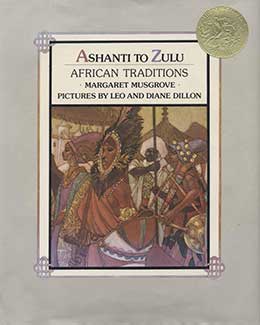

Another book about African culture won a Caldecott Honor in 1977, just two years after the Feelings’ book. With Ashanti to Zulu: African Traditions, Margaret Musgrove presents 26 different African groups and their traditions and customs. Leo and Diane Dillon created the art for this book in pastels, watercolors, and acrylics. “In order to show as much as possible about each different people, in most paintings they have included a man, a woman, a child, their living quarters, an artifact, and a local animal, though in some cases these different elements would not ordinarily be seen together” (Musgrove, 1976).

Musgrove lived and studied in Ghana and did extensive research to create correct portrayals of the variety of people found in Africa. The Dillons did further research to render accurate illustrations. A map on the last page of the book shows where all the various people live on the African continent.

Each alphabet letter presents a different ethnic group on a separate page: A for Ashanti, B for Baule, and C for Chagga. The pages follow the same formal pattern with the illustrations placed above white text blocks. Text and paintings are framed by parallel black and gold lines separated by white space. The black and gold lines are connected at the corners with Kano Knots which symbolize “endless searching — a design originally used in the then-flourishing city of Kano in northern Nigeria during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries” (Musgrove, 1976). The framing makes each illustration discrete and separates the unique people and their customs rather than lumping together all Africans.

As husband and wife, the Dillons illustrate together, handing work back and forth, so it is not done by one or the other but by what they call the “Third Artist.” Their work is sometimes described as “decorative realism” (Haber, 2020), but Leo Dillon said, “We gave away our separate styles [with the Third Artist], and in doing so realized that we opened ourselves to every style that ever existed on the face of the earth. We try to fit our style to the story that goes with it” (TeachingBooks, 2005).

The above books are thematically connected with each depicting distinct African people and their cultures. Continuing with a thematic connection, the following set of books focuses on animals, fantastical or real.

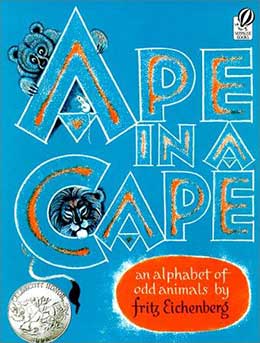

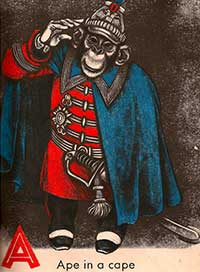

Ape in a Cape: An Alphabet of Odd Animals won a Caldecott Honor in 1953. Fritz Eichenberg dedicated the book to his son Timothy and his friends, the fox and the hare that appear with Timothy on the dedication page illustration and also in the book.

His son, who was five at the time, watched him while he was creating the illustrations. Though known as a master of wood engraving, the illustrations are not woodcuts. The illustrations are actually a monotype medium. Eichenberg described the process in an interview. “The monotype, as the name indicates, it’s a one-shot proposition. You can paint on a piece of glass with printing ink, or with oil paint, or even with gouache and put a piece of paper on top of it, and rub it, rub the back, and you come up with an image. It’s a rather primitive technique. But it allows you tremendous freedom, and you can work with great speed” (Brown, 1980). Due to the expense of printing in full color at that time, his editor requested that he do color separations. So he did. “.…there were three colors each, three times 24, color separations, in black on acetate. It’s a kind of lithographic technique, and they look like color lithography, actually” (Brown, 1980).

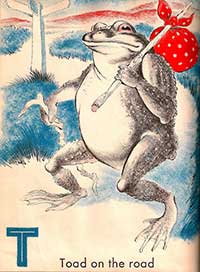

With its rhyming scheme and amusing pictures, Eichenberg helps develop an awareness of words. All of the animals, except the unicorn, are real, but many appear in imaginative situations such as the “Ape in a cape,” the “Carp with a harp,” and the “Toad on the road.”

illustration from Ape in a Cape: An Alphabet of Odd Animals, illustration © Fritz Eichenberg. Published by Houghton Mifflin, 1952.

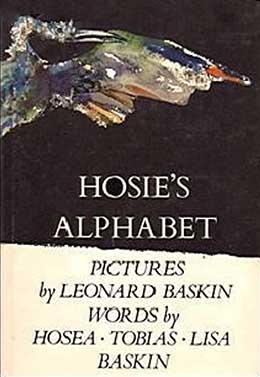

Perhaps more imaginative than Ape in a Cape is the Baskin family’s Hosie’s Alphabet. Though most of the letters signify real animals, four do not: The “D is for demon,” “G A ghastly garrulous gargoyle,” “U The invisible unicorn,” and for some reason, “X The dragon of the alphabet.” Leonard Baskin illustrated creatures selected by his then three-year-old son Hosie, and Hosie’s brother Tobias and mother Lisa supplied the elegant adjectives, truly a family endeavor.

Perhaps more imaginative than Ape in a Cape is the Baskin family’s Hosie’s Alphabet. Though most of the letters signify real animals, four do not: The “D is for demon,” “G A ghastly garrulous gargoyle,” “U The invisible unicorn,” and for some reason, “X The dragon of the alphabet.” Leonard Baskin illustrated creatures selected by his then three-year-old son Hosie, and Hosie’s brother Tobias and mother Lisa supplied the elegant adjectives, truly a family endeavor.

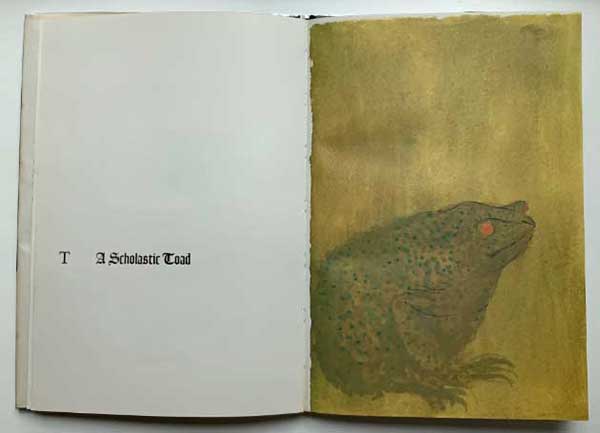

The striking watercolor and ink illustrations captured a 1973 Caldecott Honor. The wraparound jacket portrays a fancifully colored heron in flight while the “H Hosie’s heron” shows a staid, standing blue heron. The eagle and whale fill double-page spreads, but the rest of the creatures appear on the recto pages with letters and words facing on the verso. No context is provided in the illustrations as the backgrounds are either colored or white negative space. Fonts vary in size, style, capitalization, and placement on the page without any apparent pattern or reason. Exceptions include the “F A furious fly” in a very tiny font to describe the lone small fly on the facing page, and the “R The rhinoceros express” in a huge font. The “T A Scholastic Toad” appears in a gothic font, but there isn’t anything particularly scholarly about the illustration of the toad. A young child might not focus on the typography, but it certainly adds interest.

The realistic paintings depict common animals and some uncommon animals, such as the kiwi and zebu, not ordinarily found in alphabet books. Baskin followed this unique alphabet book with the equally delightful Hosie’s Aviary (1979), Hosie’s Zoo (1981), and Book of Dragons (1985), all assisted by Hosie.

Contributions by Hosea, Tobias, and Lisa Baskin. Published by Viking Children’s Books, 1972.

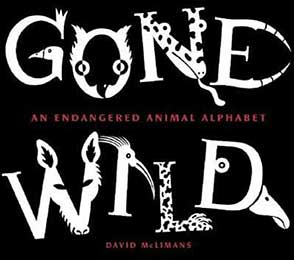

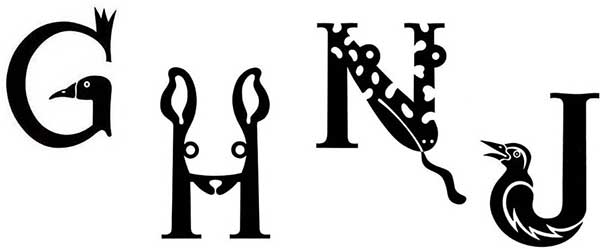

The final book has an animal and environmental theme. David McLimans won a Caldecott Honor in 2007 with his illuminated letters in Gone Wild: An Endangered Animal Alphabet. The status of the featured animals range from vulnerable to critically endangered, and some are familiar, such as the spotted owl, while others, such as the spotted-tail quoll, are less familiar. All are partially incorporated into the form of the alphabetical letter that begins its name, one letter for each page.

The final book has an animal and environmental theme. David McLimans won a Caldecott Honor in 2007 with his illuminated letters in Gone Wild: An Endangered Animal Alphabet. The status of the featured animals range from vulnerable to critically endangered, and some are familiar, such as the spotted owl, while others, such as the spotted-tail quoll, are less familiar. All are partially incorporated into the form of the alphabetical letter that begins its name, one letter for each page.

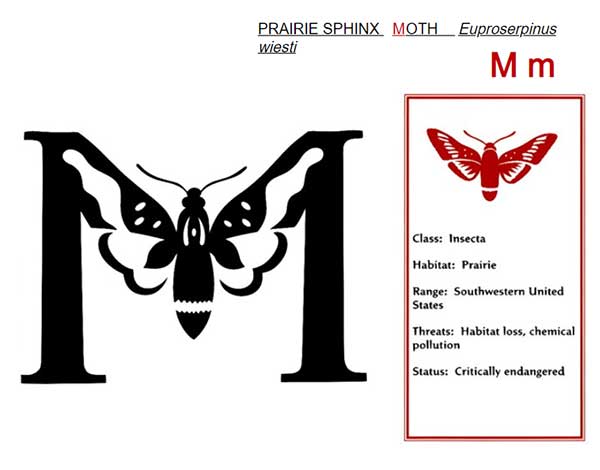

An animal depicted within a large black capital letter dominates each page. A red upper and lower case letter in another font is located beneath the common and scientific name of the animal in the upper right corner. Below that is a vertical box with a red silhouette of the animal. The box includes the animal’s class, habitat, range, threats, and status. Situated against white negative space, the same red silhouettes of the animals appear on the endpapers, thirteen in the front and thirteen in the back. The back matter consists of 26 horizontal boxes with the silhouettes of the animals in red against black backgrounds. More information about the animals can be found here, as well as a list of books for further reading and a list of organizations that help endangered animals.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, 2016.

The copyright page states, “The illustrations for this book were created using pencil, pen, brush, India ink, bristol board and computer.” Using just black and red ink, McLimans creates a clean, uncluttered design for each page. He states in his author note that “The twenty-six endangered animals featured were selected because they presented visual opportunities….In a way, this alphabet is a return to picture writing. The challenge for me in creating these images was finding endangered animals whose shape and form fit naturally together with the letters that begin their names” (McLimans, 2006). He not only presents endangered animals in an inventive way, he alerts people of all ages to the environmental issues the animals are confronting.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, 2016.

Many of the books discussed in this article may not be familiar because they are dated or out of print. As all of them are Caldecott Honor books, all of the titles are noteworthy, but the honor books tend to receive less attention than the medal books.

ABC books are plentiful, and they can be quite sophisticated, serving as introductions to topics, jumping off points for further research, or just plain fun. What differentiates them from one another is their cleverness and/or their artwork. As picture books, abecedaria seem more the work of the illustrator than the author. With all of its possibilities, the alphabet has inspired both authors and illustrators in the past, and continues to inspire them today.

Picture Books Cited

Baskin, H., Baskin, T., Baskin, L., & Baskin, L. (1972). Hosie’s alphabet. Viking Press.

Eichenberg, F. (1952). Ape in a cape: An alphabet of odd animals. Voyager Books (Harcourt).

Feelings, M. & Feelings, T. (1974). Jambo means hello: Swahili alphabet book. The Dial Press.

McLimans, D. (2006). Gone wild: An endangered animal alphabet. Walker & Company.

Musgrove, M. & Dillon, L. & D. (1976). Ashanti to Zulu: African traditions. Dial Books for Young Readers.

References

ALSC (Association for Library Services to Children). (2022). Ape in a cape: An alphabet of odd animals. Book and Media Award Shelf.

Brown, R. (1980). Oral history interview with Fritz Eichenberg, 1979 May 14-December 7. Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Haber, K. (2020, April). Leo and Diane Dillon: The third artist rules. Locus Online.

Teaching Books. (2005, September). Leo and Diane Dillon. TeachingBooks.net.

UNESCO. (2022, July). Kiswahili is a language that speaks to both past and present. African Renewal.