According to Guinness World Records, the Christian Bible is the best selling book of all time (Guinness World Records, 2023). With its myriad stories, the Bible provides inspiration and instruction for many, and it is a staple of Sunday School and Vacation Bible School. There are numerous picture books based on Bible stories, and five of those have won Caldecott Awards.

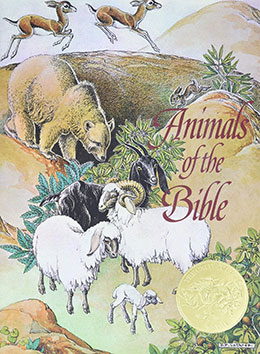

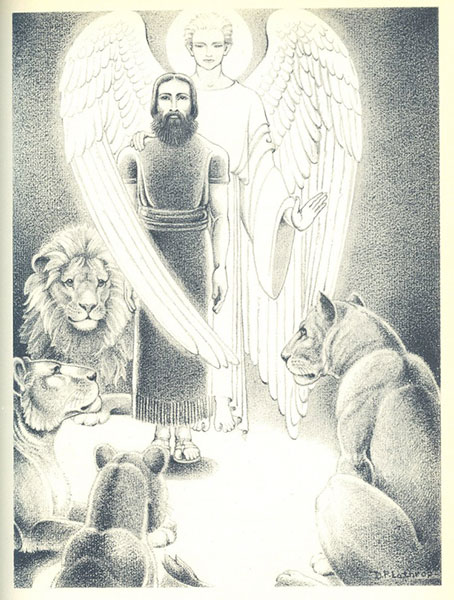

Helen Dean Fish’s Animals of the Bible, illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop, was the very first book to win the Caldecott Medal in 1938. In her Forward, Fish states, “Interest in animals is almost universal” (Fish, 1938, p. VI). This is especially true for children. Lathrop illustrated stories that included The Serpent and Eve, Abraham’s Ram, and Daniel’s Lions.

Helen Dean Fish’s Animals of the Bible, illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop, was the very first book to win the Caldecott Medal in 1938. In her Forward, Fish states, “Interest in animals is almost universal” (Fish, 1938, p. VI). This is especially true for children. Lathrop illustrated stories that included The Serpent and Eve, Abraham’s Ram, and Daniel’s Lions.

On the verso, the one-page stories that Fish selects face formal full-page black and white lithographs framed with white borders (ALSC, 2020, p. 168) on the recto. Three double-page illustrations interspersed throughout the book add variety. While each Caldecott Committee can determine what constitutes a picture book, this book might best be considered an illustrated book rather than a picture book.

written by Helen Dean Fish, published by Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1937

In a picture book, as much as half, or more than half, of the narrative is carried by the illustrations. Lathrop’s illustrations simply create a scene that features an animal or animals from the accompanying story. “During the drawing of these pictures, the artist studied not only the fauna but the flora of the Bible lands and times, and each desert rose, as well as each goat and turtle dove is as true to natural history as is possible to be” (Fish, 1938, VI). The animals are detailed and accurate with texture and movement, but the people are more static and flat. While children may enjoy her illustrations in Animals of the Bible, it is unlikely that this is a very popular book due to the difficult language of the King James Version of the Bible text.

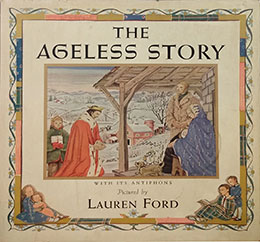

Perhaps because of its connection to Christmas, a Bible story that is popular with children is the story of Jesus’ birth. Lauren Ford wrote and illustrated The Ageless Story: With Its Antiphons and won a Caldecott Honor for it in 1940. Unlike Lathrop, Ford sets her story in the late 1800s New England. In a letter she wrote to her goddaughter Nina to whom she dedicated the book, Ford explains the reason she did this. “You will see landscapes that you know, roads that you have taken, the Baby Jesus is born in the barn down the hill. It is because He belongs to you and me …. If Jesus doesn’t look like a little boy, like the boy next door, He won’t seem like a boy to you and He won’t look real” (Ford, 1939, A Letter).

Perhaps because of its connection to Christmas, a Bible story that is popular with children is the story of Jesus’ birth. Lauren Ford wrote and illustrated The Ageless Story: With Its Antiphons and won a Caldecott Honor for it in 1940. Unlike Lathrop, Ford sets her story in the late 1800s New England. In a letter she wrote to her goddaughter Nina to whom she dedicated the book, Ford explains the reason she did this. “You will see landscapes that you know, roads that you have taken, the Baby Jesus is born in the barn down the hill. It is because He belongs to you and me …. If Jesus doesn’t look like a little boy, like the boy next door, He won’t seem like a boy to you and He won’t look real” (Ford, 1939, A Letter).

Following the letter,The Ageless Story is told in four pages of dense text that begins with the legend of Saint Anne and the birth of Mary. The story proceeds based on the Gospel of Saint Luke starting with the angel Gabriel’s visit to Mary announcing the birth of Jesus, continuing through the nativity, and concluding with the child Jesus at the age of twelve.

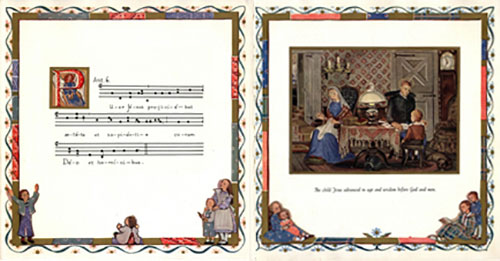

The twelve two-page spreads that illustrate the story have an identical formal design. The antiphon, a Christian chant, is found on the verso and an illustration from the story of Jesus on the recto. All pages have borders that incorporate images of children. The antiphon page borders include children singing while the illustration page borders show children reading and listening to the story. The antiphons look like illuminated manuscripts and begin with a small square image of the chant’s first letter decorated with an angel reminiscent of medieval religious art.

Illustrations are painted in full color within gold borders surrounded by the page borders. Full color was unusual for a children’s book published at that time. The New England setting and 19th century clothing clash with the medieval style of the book, but that might not be noticeable to children, and it may indeed make the story seem more real for them as Ford intended.

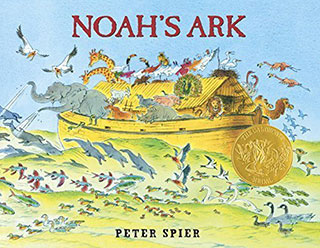

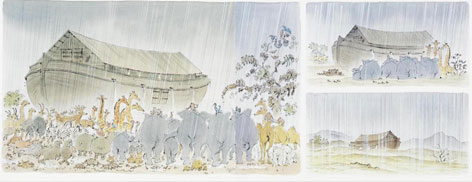

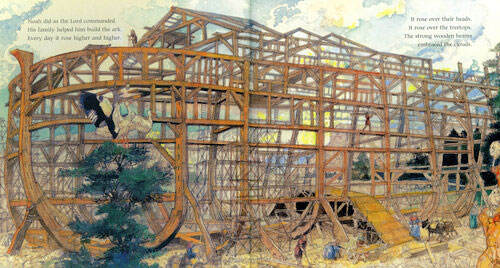

Whether real or not, flood stories are included in several ancient texts, and the next three Caldecott Award books are based on the story of Noah. Noah’s Ark, illustrated by Peter Spier, won the Caldecott Medal in 1978. He translated the story from a seventeenth century Dutch poem by Jacobus Revius. Spier himself was Dutch-American (Robinson, 2002, p. 428). The story begins on the front endpapers showing Noah working in his garden while soldiers march away from a ravaged fiery city in the background. Words on this page state “… But Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord.” Illustrations continue the story on the half title and the title pages, and then the poem appears on the recto facing the fourth illustration of the book. These are the only words. The rest of the book contains delightfully detailed and sometimes humorous illustrations right through the back endpapers showing Noah once again working in his garden, a new garden, underneath a rainbow. Spier stated, “Writing and drawing are two of the same art forms. What you say in the text, you no longer need to say in the picture and vice versa” (Robinson, 2002, p. 429). His illustrations need no words.

Whether real or not, flood stories are included in several ancient texts, and the next three Caldecott Award books are based on the story of Noah. Noah’s Ark, illustrated by Peter Spier, won the Caldecott Medal in 1978. He translated the story from a seventeenth century Dutch poem by Jacobus Revius. Spier himself was Dutch-American (Robinson, 2002, p. 428). The story begins on the front endpapers showing Noah working in his garden while soldiers march away from a ravaged fiery city in the background. Words on this page state “… But Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord.” Illustrations continue the story on the half title and the title pages, and then the poem appears on the recto facing the fourth illustration of the book. These are the only words. The rest of the book contains delightfully detailed and sometimes humorous illustrations right through the back endpapers showing Noah once again working in his garden, a new garden, underneath a rainbow. Spier stated, “Writing and drawing are two of the same art forms. What you say in the text, you no longer need to say in the picture and vice versa” (Robinson, 2002, p. 429). His illustrations need no words.

Warm colors of chaotic scenes within the ark contrast with darker dismal colors outside during the flood. Using F pencil, white pencil, and watercolors (ALSC, 2020, p. 134), Spier must have chuckled to himself while imagining and depicting the absurdity of Noah fitting two of every animal on his ark along with the logistics of penning and feeding them, not to mention all the manure shoveling it entailed. The minutiae of daily life on the ark gives the reader much to examine.

One criticism of the book is that Spier included clear glass jars housing insects (Lacy, 1986, p. 212). Something else to consider is that while Spier doesn’t show the grisly details of animals left behind drowning, there are illustrations that cause the reader to imagine it. Children may have difficulty reconciling a loving God punishing innocent animals. They may have questions.

In his Caldecott Acceptance Speech, Spier said all the Noah’s ark books he reviewed present the story as a “joyous sun-filled Caribbean cruise” (Spier, 1978, ALSC). It couldn’t have been. He decided there was room for one more book.

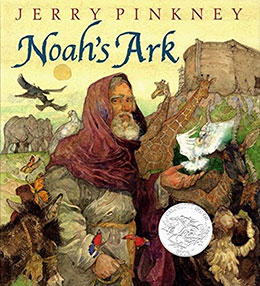

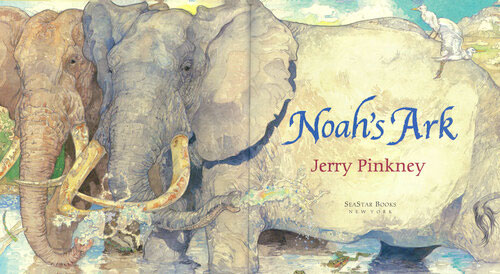

Apparently Jerry Pinkney felt the same way because his Noah’s Ark won a Caldecott Honor in 2003. Pinkney said he was drawn to the Noah story “.…by its epic scope. In this work, the extraordinary beauty and power of nature truly inspired me. I was also fascinated by the juxtaposition of humankind’s inherent responsibility and the opportunity for a second chance” (Pinkney, 2002, back jacket flap). He dedicates the book “To the caretakers of all things, big and small.”

Pinkney’s pencil, colored pencil, and watercolor (ALSC, 2020. p. 113) double-page paintings begin on the front endpapers fittingly with the Genesis text, “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.” It depicts an underwater closeup of an ancient whale and sharks with a dinosaur on land in the distance. This is followed by a textured painting of a pair of elephants bleeding off the title page, the title printed on an elephant’s belly.

Using mostly an earth tone palette, Pinkney presents varied points of view of the ark from a detailed closeup of its structure, to an aerial perspective, to the hull of the ark from the sea below. Interestingly, this view shows the ark floating above deserted, ruined cities with sea creatures swimming through them, but it does not depict drowned people or animals.

The back endpapers close the story with God’s promise after the flood. Pinkney presents a view of the earth centered on the double-page spread surrounded by rainbows. The dark blue background of the verso includes the moon in the lower center and the light blue background of the recto shows the sun in the upper center. This perfect balance provides a satisfying ending to a story of salvation and peace based on trust and obedience.

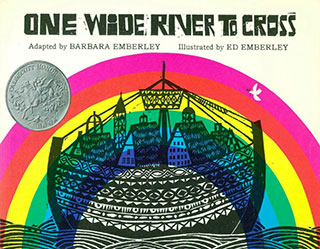

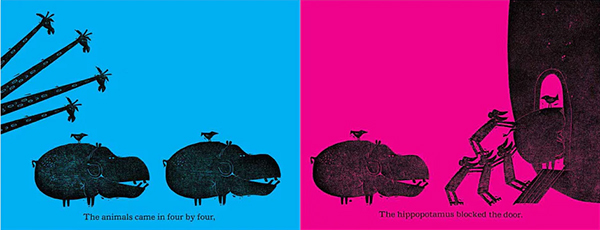

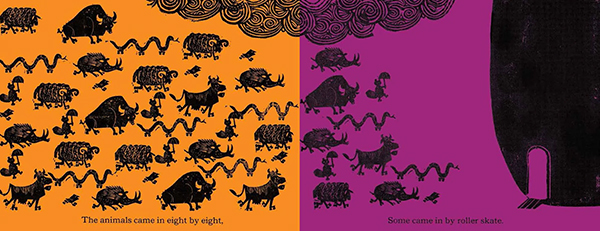

The final book is not really a flood story but a counting book based on the story of Noah’s ark. One Wide River to Cross won the sole Caldecott Honor in 1967. Barbara Emberly adapted the American folk song and included the music and lyrics at the end of the book. Her husband Ed Emberly, best known for his instructional drawing books, created the black woodcut illustrations (ALSC, 2020, 143). The book provides singable counting practice from 1 – 10 while page turns reveal a variety of animals humorously boarding the ark. “The animals came in eight by eight. Some came in by roller skate.”

The final book is not really a flood story but a counting book based on the story of Noah’s ark. One Wide River to Cross won the sole Caldecott Honor in 1967. Barbara Emberly adapted the American folk song and included the music and lyrics at the end of the book. Her husband Ed Emberly, best known for his instructional drawing books, created the black woodcut illustrations (ALSC, 2020, 143). The book provides singable counting practice from 1 – 10 while page turns reveal a variety of animals humorously boarding the ark. “The animals came in eight by eight. Some came in by roller skate.”

“Ed Emberly used his own press to print the woodcuts for the book. Separate blocks of wood were cut for each figure or part of a design, then inked and pressed on rice paper. One page contains as many as fifty-seven different impressions” (Kirk, 2005, p. 187). The vibrantly colored background of each page contrasts with the woodcuts. The color of the recto becomes the color of the verso with a page turn providing continuity. Initially, no clouds appear across the tops of the pages, but when they do appear, they become increasingly larger and more threatening until the final spread: a bright sun on a yellow page opposite the only white page that depicts the ark and a rainbow. Children familiar with the Bible story might wonder why the animals don’t come in pairs, but they will enjoy giggling over the illustrations.

The Bible inspires both spiritually and artistically. Its stories stir illustrators to share their interpretations providing us visual details the text lacks. In addition to these five Caldecott Award books, the numerous picture books of the Bible make the stories come alive for children and provide opportunities to discuss not only the content but also to compare the variety of artistic styles.

Picture Books Cited

Archer, Micha. Wonder Walkers. New York: Nancy Paulsen Books/Penguin Random House, 2021.

Emberly, B. & Emberly, E. (2015). One wide river to cross. AMMO. (1966).

Fish, H. D. & Lathrop, D. P. (1998). Animals of the Bible (60th anniversary ed.). HarperCollins Publishers. (1937).

Ford, L. (1939). The ageless story: With its antiphons. Dodd, Mead & Co.

Pinkney, J. (2002). Noah’s ark. SeaStar Books.

Spier, P. (1977). Noah’s ark. Doubleday Book for Young Readers.

References

-

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). (2020). The Newbery and Caldecott Awards: A guide to the medal and honor books. American Library Association.

- Guinness World Records. (2023). Best-selling book. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/best-selling-book-of-non-fiction

- Kirk, C.A. (2005). Companion to American children’s picture books. Greenwood Press.

- Robinson, L., (2002). The essential guide to children’s books and their creators (A. Silvey, Ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

- Spier, P. (1978). 1978 Caldecott acceptance speech. Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/811