“There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away””

Emily Dickinson

Some Caldecott Award illustrators specify settings through identifying details of a location such as a bridge or a building. Books with settings in the United States were presented in Part 1. Books with settings in Europe are presented in Part 2.

From Canada we sail across the Atlantic Ocean with Captain Harry Colebourn and his pet bear Winnie, short for Winnipeg, to arrive on the Salisbury Plain in southern England. Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear, written by Lindsay Mattick, is a story about her great-grandfather Harry who was a veterinarian during World War I. He acquired his bear cub at a train station while traveling as a soldier. When Harry realizes he can’t take Winnie into battle with him, he makes the heart-wrenching decision to give her up to the care of the London Zoo.

From Canada we sail across the Atlantic Ocean with Captain Harry Colebourn and his pet bear Winnie, short for Winnipeg, to arrive on the Salisbury Plain in southern England. Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear, written by Lindsay Mattick, is a story about her great-grandfather Harry who was a veterinarian during World War I. He acquired his bear cub at a train station while traveling as a soldier. When Harry realizes he can’t take Winnie into battle with him, he makes the heart-wrenching decision to give her up to the care of the London Zoo.

Illustrator Sophie Blackall won the 2016 Caldecott Medal for her art in Finding Winnie. In an interview she said, “I use Chinese ink to paint the gray tones, and watercolor washes over the top. I use Schmincke watercolors, in a tin set my father gave me when I was 15. After 35 books I’ve had to replace a few of the colors, but they last such a long time” (Danielson, 2015).

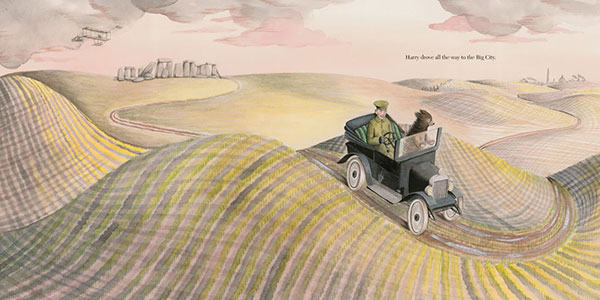

Blackall visited England to do extensive research for this story. When interviewed she said, “I traveled the road Harry and Winnie took to the city, past Stonehenge.”

of the world’s most famous bear, published by Little, Brown/Hachette

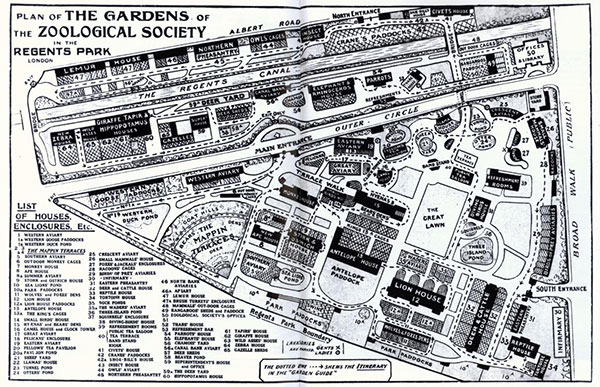

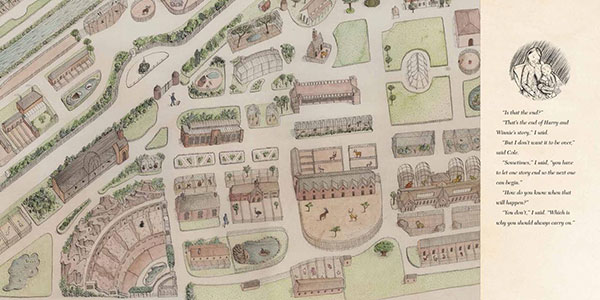

She also shared, “I visited the archives of the London Zoo to see photographs and news clippings and the ledger in which Winnie’s arrival was recorded by the zookeeper in exquisite copperplate” (Snelson, 2016). She used this 1913 map of the zoo as a “footprint” for her own map before researching all the buildings (Danielson, 2015).

of the world’s most famous bear, published by Little, Brown/Hachette

It is at the zoo that Christopher Robin and his father A. A. Milne meet Winnie, a friendship develops between the boy and the bear, and she becomes famous as Winnie the Pooh.

It is at the zoo that Christopher Robin and his father A. A. Milne meet Winnie, a friendship develops between the boy and the bear, and she becomes famous as Winnie the Pooh.

She lived at the London Zoo from 1914 until her death in 1934 (West, 2003). There is a statue of Winnie and Harry at both the London Zoo and the zoo in Winnipeg.

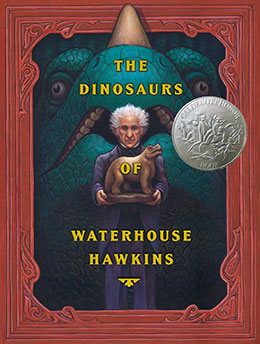

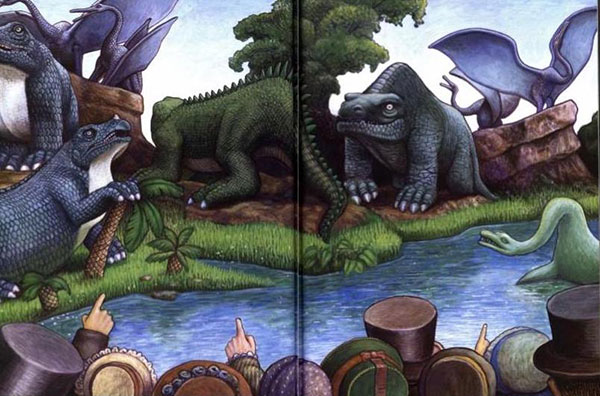

Another story takes place in London, this one written by Barbara Kerley and illustrated by Brian Selznick. We travel back in time to Victorian England and meet Waterhouse Hawkins who built dinosaurs to “prowl the grounds of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s new art and science museum, the Crystal Palace.” Selznick won a 2002 Caldecott Honor for his dramatic acrylic paintings of dinosaurs that Hawkins built in collaboration with scientist Richard Owen, the man who created the word “dinosaur.”

The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins explains how Hawkins made drawings, models, and finally life-size sculptures of dinosaurs based simply on the few fossil bones that had been discovered at that time. Most people didn’t even know about dinosaurs, but Hawkins’ work created excitement about them that lasts even today. As explained in the extensive author and illustrator’s notes, the Crystal Palace was originally built for the Great Exhibition at Hyde Park in 1851, but was moved to Sydenham, a southern suburb of London, in 1852. Waterhouse built his dinosaurs for the grand reopening of the palace, and the dinosaurs still reside as a special feature in the park. Selznick traveled to England to study them. Because the sculptures were constructed based upon the limited knowledge available almost 200 years ago, they do not accurately reflect what we know about dinosaurs today (Kerley & Selznick, 2001). However, by standards of any time, they are impressive, and the large format of the book allows Selznick to emphasize their size.

The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins explains how Hawkins made drawings, models, and finally life-size sculptures of dinosaurs based simply on the few fossil bones that had been discovered at that time. Most people didn’t even know about dinosaurs, but Hawkins’ work created excitement about them that lasts even today. As explained in the extensive author and illustrator’s notes, the Crystal Palace was originally built for the Great Exhibition at Hyde Park in 1851, but was moved to Sydenham, a southern suburb of London, in 1852. Waterhouse built his dinosaurs for the grand reopening of the palace, and the dinosaurs still reside as a special feature in the park. Selznick traveled to England to study them. Because the sculptures were constructed based upon the limited knowledge available almost 200 years ago, they do not accurately reflect what we know about dinosaurs today (Kerley & Selznick, 2001). However, by standards of any time, they are impressive, and the large format of the book allows Selznick to emphasize their size.

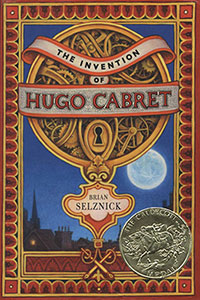

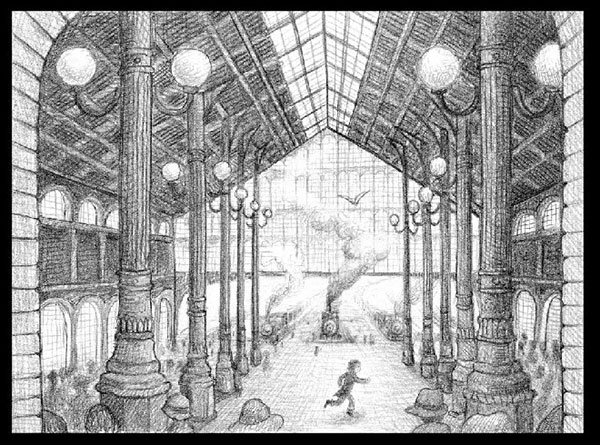

A few years later, Selznick traveled to Paris for the setting of his 2008 Caldecott Medal book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, a more than 500-page book that redefined the concept of a picture book. Image and text narration take turns to tell the story of orphaned Hugo who secretly works as a clock keeper in a 1931 Paris train station and meets the famous filmmaker Georges Méliès. Using pencil and cross hatching for powerful light and shadow effects, Selznick’s realistic black and white illustrations are reminiscent of silent films. During his three trips to Paris, Selznik immersed himself in the culture of the city. “I started by visiting all the train stations in the city….The stations were built in the nineteenth century with grand staircases, ornate columns, pointed glass roofs, palm trees in huge pots, sculptures, elaborate façades, and, of course, huge clocks everywhere. The station where Méliès worked, the Gare Montparnasse….is the only one that has been torn down, so to create the train station in my book, I used vintage photographs of the original station, as well as bits and pieces from many other stations in Paris, especially the Gare du Nord” (McCarthy, 2012).

A few years later, Selznick traveled to Paris for the setting of his 2008 Caldecott Medal book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, a more than 500-page book that redefined the concept of a picture book. Image and text narration take turns to tell the story of orphaned Hugo who secretly works as a clock keeper in a 1931 Paris train station and meets the famous filmmaker Georges Méliès. Using pencil and cross hatching for powerful light and shadow effects, Selznick’s realistic black and white illustrations are reminiscent of silent films. During his three trips to Paris, Selznik immersed himself in the culture of the city. “I started by visiting all the train stations in the city….The stations were built in the nineteenth century with grand staircases, ornate columns, pointed glass roofs, palm trees in huge pots, sculptures, elaborate façades, and, of course, huge clocks everywhere. The station where Méliès worked, the Gare Montparnasse….is the only one that has been torn down, so to create the train station in my book, I used vintage photographs of the original station, as well as bits and pieces from many other stations in Paris, especially the Gare du Nord” (McCarthy, 2012).

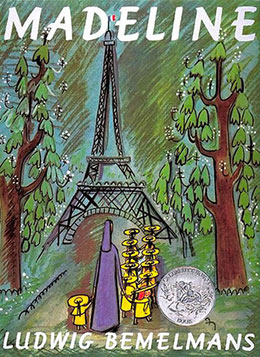

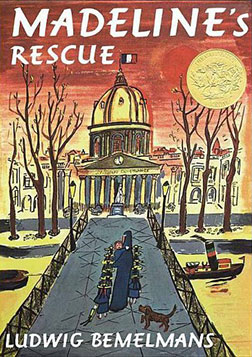

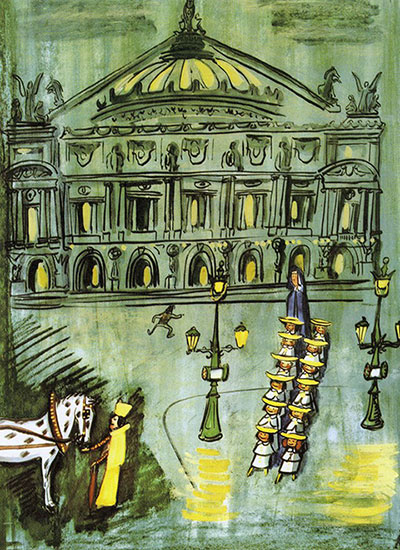

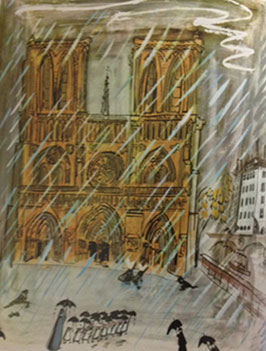

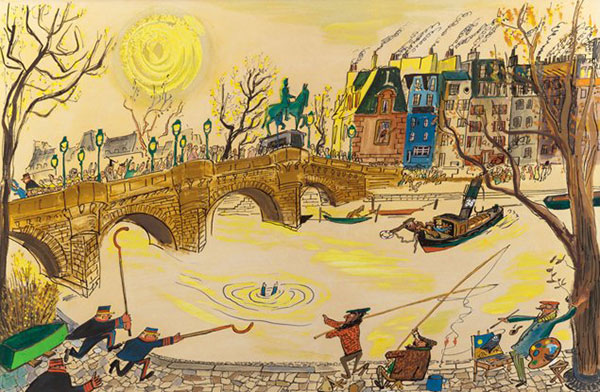

Two more Caldecott Award books take place in Paris: Ludwig Bemelmans’ Madeline, a 1940 Caldecott Honor, and Madeline’s Rescue, the 1954 Caldecott Medal.

The idea of Madeline began when Bemelmans had a biking accident and was hospitalized on a family vacation in Paris (Bemelmans, 1954). But, as Ethel Heins wrote, “In a way Paris is the chief character in the book, and is portrayed just as vividly as the enchanting Madeline. Parisian images remain fixed in the mind — Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower, the Place Vendôme, the Opéra, the Luxembourg Gardens — and all are supported by an orderly, secure, tightly plotted story” (Heins, 1988, 58). After the last page in Madeline, the Paris scenes Bemelmans painted with “brush, pen, and watercolor” (ALSC, 159), are listed. Strong, simple lines with bold colors depict these recognizable landmarks that lack architectural detail as if painted from a child’s perspective. Similar scenes appear in Madeline’s Rescue.

published by The Viking Press

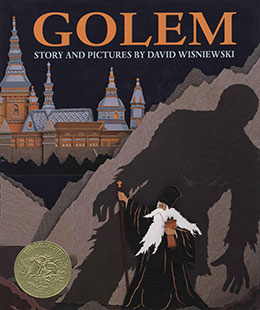

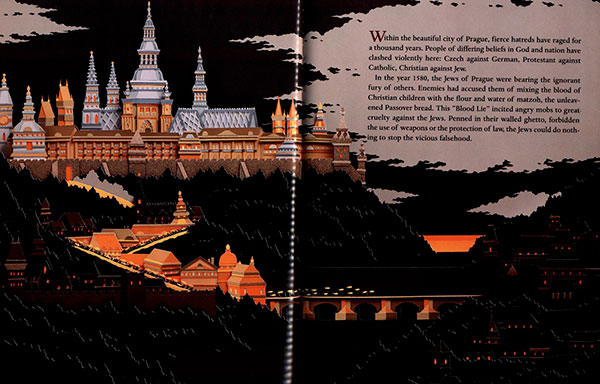

We move from Paris, called “The City of Light,” to a dark story that takes place in Prague during 1580. David Wisniewski’s Golem, the 1997 Caldecott Medal book, is the legend of Rabbi Loew who creates a man of clay, a golem, infusing the creature with life through an ancient spell. The golem’s mission is to protect the Jews from persecution which he does by wreaking terror and death. The rabbi is summoned to Prague Castle and promises the emperor he will destroy his monster after the Jews are out of danger. By this time, though, the giant has come to love life, and in a tragic ending, he is returned to clay. Of this story Wisniewski writes in his author’s note, “There is evidence of its influence in Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein” (Wisniewski, 1996).

We move from Paris, called “The City of Light,” to a dark story that takes place in Prague during 1580. David Wisniewski’s Golem, the 1997 Caldecott Medal book, is the legend of Rabbi Loew who creates a man of clay, a golem, infusing the creature with life through an ancient spell. The golem’s mission is to protect the Jews from persecution which he does by wreaking terror and death. The rabbi is summoned to Prague Castle and promises the emperor he will destroy his monster after the Jews are out of danger. By this time, though, the giant has come to love life, and in a tragic ending, he is returned to clay. Of this story Wisniewski writes in his author’s note, “There is evidence of its influence in Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein” (Wisniewski, 1996).

Wisniewski’s somber colors add dramatic effect to the story. Dilys Evans (1997) describes how he works.

After the manuscript for the text is deemed perfect, he proceeds to do the first pencil sketches on layout paper, followed by more detailed black ink. Once the drawings are approved by the editor, he uses a color marker to establish color consistency, adding to the growing mood of the book. Then detailed tracings are made, one for each spread, and these are the final compositions. Each spread is then transferred, with carbon, to colored papers, and the cutting, positioning, and assembling with double-stick photo-mounting and foam tape takes place. For each book, David uses between eight hundred and one thousand blades for his X‑Acto knife (p. 426).

Wisniewski then works with a photographer to light his intricately cut paper illustrations for the best, almost theatrical, effect to show depth and texture. In his Caldecott speech, he said, “As a self-taught artist and writer, I rely on instincts developed through years of circus and puppet performance to guide a story’s structure and look.” (Wisniewski, 1997, p. 20). It is interesting to note that a previous book, The Golem: A Jewish Legend by Beverly Brodsky McDermott, won a Caldecott Honor in 1977.

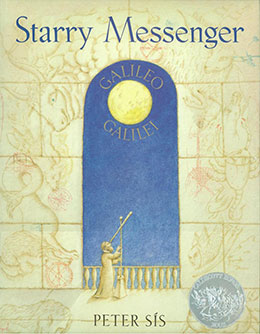

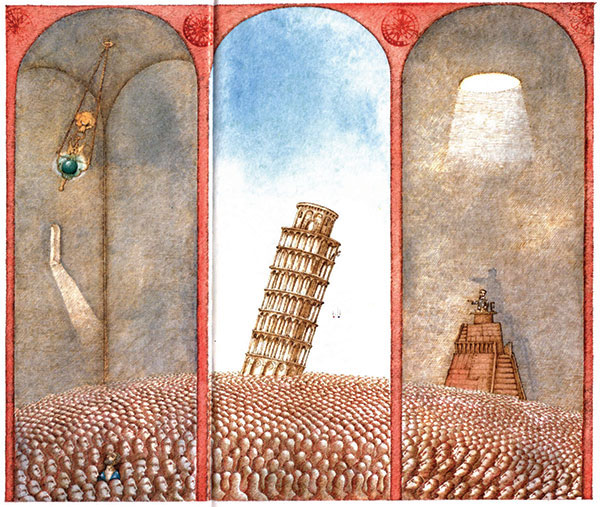

Peter Sís grew up in Prague during Communist rule and set several of his stories there. However, Starry Messenger: A Book Depicting the Life of a Famous Scientist, Matematician, Astronomer, Philosopher, Physicist, Galileo Galilei, a 1997 Caldecott Honor book, takes place in Pisa, Italy, where Galileo was born in 1564. In the illustration below, Galileo is demonstrating his Law of Falling Objects in 1611 that states that two objects of unequal weight fall at the same rate.

Peter Sís grew up in Prague during Communist rule and set several of his stories there. However, Starry Messenger: A Book Depicting the Life of a Famous Scientist, Matematician, Astronomer, Philosopher, Physicist, Galileo Galilei, a 1997 Caldecott Honor book, takes place in Pisa, Italy, where Galileo was born in 1564. In the illustration below, Galileo is demonstrating his Law of Falling Objects in 1611 that states that two objects of unequal weight fall at the same rate.

Sís’s “pen and brown ink and watercolor” (ALSC, p. 112) illustrations resemble some of Galileo’s own drawings, and he includes handwritten excerpts from Galileo’s book The Starry Messenger as well as colorful maps from that time period (Kid Lit Review, 2017).

Galileo proved that earth was not the center of the universe, going against the teachings of the Catholic Church. He was tried in the Pope’s court, and was “condemned to spend the rest of his life locked in his house under guard.” Sís wrote, “When I was young, I was fascinated by people who could go places. I was in a country where I couldn’t go anyplace, and I liked people going to the moon and stories about explorers. Galileo was in prison, but he still was able to go places with his mind” (Sís, 2004). This is what we experience when we travel with books.

The Caldecott Award is given to American illustrators. Perhaps that is why there is a preponderance of settings in the United States and Europe. However, Caldecott Award books take place in many different countries such as Lon Po Po in China, The Boy of the Three Year Nap in Japan, or The Cat Man of Aleppo in Syria. But these books do not identify specific locations through the illustrations such as the books discussed above do. For more books with non-Western settings, you might look at international illustrator awards and lists such as the Association of Illustrators World Illustrator Awards, the Hans Christian Andersen Book Award, and the USBBY Outstanding Internation Books List, among others.

Picture Books Cited

Bemelmans, L. (1939). Madeline. Simon & Schuster.

Bemelmans, L. (1953). Madeline’s rescue. Viking.

Kerley, B. & Selznick, B. (2001). The dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins: An illuminating history of Mr. Waterhouse Hawkins, artist and lecturer. Scholastic.

McDermott, B. B. (1976). The golem: A Jewish legend. J. B. Lippincott.

Mattick, L. & Blackall, S. (2015). Finding Winnie: The true story of the world’s most famous bear. Little, Brown/Hachette.

Selznick, B. (2007). The invention of Hugo Cabret. Scholastic.

Sís, P. (1996). Starry messenger: A book depicting the life of a famous scientist, mathematician, astronomer, philosopher, physicist, Galileo Galilei. Farrar Straus Giroux.

Wisniewski, D. (1996). Golem. Clarion.

Photo Images

Bell, B. (n.d.) Stonehenge at sunrise. Unsplash.

Cain, J. (2008). Megalosaurus. Professor Joe Cain.

Diliff. (n.d.) Gare du Nord train station. Wikipedia.

Fidler, J. (2015). Prague Castle. Flicker.

Hass, P. (2013). Notre Dame. Wikipedia.

Irene. (2006). Tower of Pisa. Flicker.

Danielson, J. (2015). London Zoo 1913. Seven impossible things before breakfast.

Madelyn. (2015). Pont Neuf. In an old house in Paris all covered with vines. Paris Pefect.

Rivera, P. (2009). Paris Opera. Wikipedia.

Winnie statue at London Zoo. Wikipedia.

Wright, I. (2014). Iguanadon. Wikipedia.

References

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). (2017). The Newbery and Caldecott Awards: A guide to the medal and honor books. American Library Association.

Bemelmans, L. (1954). Caldecott Award acceptance. Horn Book Magazine, 30 (4), 270 – 276.

Danielson, J. (2015). One picture-book roundtable before breakfast #4: Featuring the women of Finding Winnie. Seven Impossible Things before Breakfast.

Evans, D. (1997). David Wisniewski. Horn Book Magazine, 73 (4), 424 – 427.

Heinz, E. (1988). Ludwig Bemelmans. In J. M. Bingham (Ed.). Writers for children (pp. 55 – 61). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Kid Lit Review. (2017). Kid Lit Review of Starry Messenger by Peter Sis. Rhapsody in Books.

McCarthy, S. (2012). Hugo and the train stations of Paris. BLT.

Sis, P. (2004). In-depth written interview with Peter Sis. Teaching Books.

Snelson, K. (2016). Caldecott winner Sophie Blackall: What small thing might change the world. Shelf Awareness.

West, M. I. (2003). A children’s literature tour of Great Britain. Scarecrow Press.

Wisniewski, D. (1997). Caldecott Medal acceptance. Horn Book Magazine, 73 (4), 418 – 424.

I am so appreciative of your research and the images you’ve shared from the books and their real life counterparts! This is fascinating stuff.