Some people fondly remember listening to ghost stories told around campfires or at sleepovers. Everyone jumped at any unusual sound, then laughed when learning it was nothing sinister. It was fun and safe to be scared in a group situation. According to multiple sources, being scared and overcoming our fear is good for us, and this is especially true when reading or listening to scary stories (Capstone, n.d.; 2021). Scary stories help children learn it’s okay to be afraid, that they can confront and manage fears and emotions from a safe place. It helps them develop resiliency when they see a fictional character face a fear and solve a problem (August House, n.d.). Several Caldecott Award books could be classified as scary stories, and the artwork might be the scariest aspects of the books.

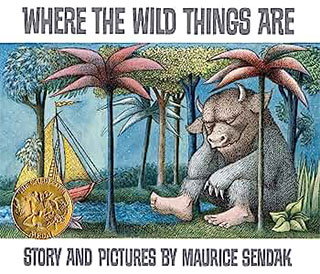

In the 1964 Caldecott Medal book Where the Wild Things Are, Max makes “mischief of one kind and another.” His mother sends him to his room without supper, and Max sails to “where the wild things are.” Author/illustrator Maurice Sendak stated, “I wanted my wild things to be frightening” (Lanes, 1998, 88), but Max is not alarmed by them at all. Hand on hip, he disdainfully observes them while they “[roar] their terrible roars and [gnash] their terrible teeth and [roll] their terrible eyes and [show] their terrible claws.” Max simply tames the comically grotesque creatures by telling them to “BE STILL!” and performing a magic trick. Wow! Talk about facing and overcoming fears. After a wild rumpus, Max returns home to the safety “of his very own room where he found his supper waiting for him and it was still hot.” Removing the hood of his wolf suit, Max sheds the wild thing persona showing that he has overcome his earlier strong emotions.

In the 1964 Caldecott Medal book Where the Wild Things Are, Max makes “mischief of one kind and another.” His mother sends him to his room without supper, and Max sails to “where the wild things are.” Author/illustrator Maurice Sendak stated, “I wanted my wild things to be frightening” (Lanes, 1998, 88), but Max is not alarmed by them at all. Hand on hip, he disdainfully observes them while they “[roar] their terrible roars and [gnash] their terrible teeth and [roll] their terrible eyes and [show] their terrible claws.” Max simply tames the comically grotesque creatures by telling them to “BE STILL!” and performing a magic trick. Wow! Talk about facing and overcoming fears. After a wild rumpus, Max returns home to the safety “of his very own room where he found his supper waiting for him and it was still hot.” Removing the hood of his wolf suit, Max sheds the wild thing persona showing that he has overcome his earlier strong emotions.

Sendak endured complaints from parents who thought children would be frightened by the illustrations of the wild things and then have nightmares. But children sent Sendak pictures of their own wild things that he said outdid his own in terms of ferocity (Arbuthnot & Sutherland). Rather than children, it may have been parents who were afraid, fearing their children would imitate Max’s bad behavior. In his Caldecott acceptance speech, Sendak said, “Where the Wild Things Are was not meant to please everybody — only children” (Sendak, 1988, 154.). Its continued popularity since its publication is a testimony to just how much the book pleases children.

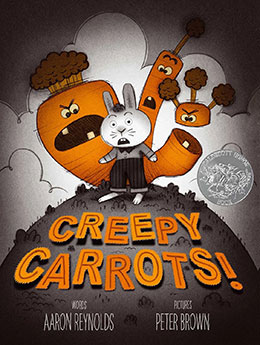

Though Sendak wanted his wild things to be frightening, he didn’t intend to write a scary story. Peter Brown did, sort of. He described his illustrations for Aaron Reynold’s 2013 Caldecott Honor book Creepy Carrots! as “spooky,” but added, “I like the idea of kids a tad on edge, but the last thing I want is to have kids have nightmares” (Kiriluk-Hill, 2013).

Though Sendak wanted his wild things to be frightening, he didn’t intend to write a scary story. Peter Brown did, sort of. He described his illustrations for Aaron Reynold’s 2013 Caldecott Honor book Creepy Carrots! as “spooky,” but added, “I like the idea of kids a tad on edge, but the last thing I want is to have kids have nightmares” (Kiriluk-Hill, 2013).

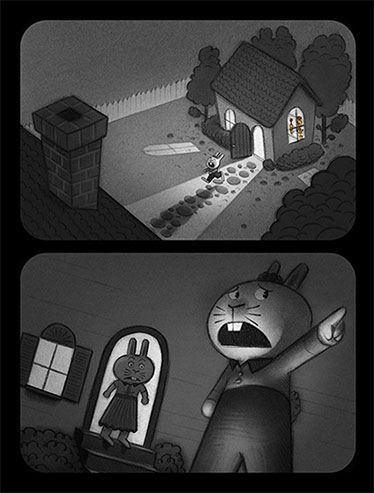

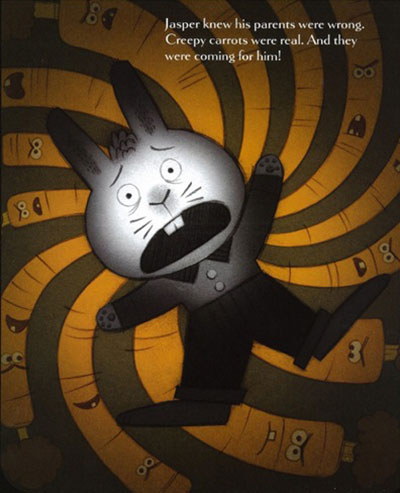

Brown spent a lot of time watching old horror movies and television programs to prepare for illustrating Creepy Carrots! He imitates the atmospheric style of film noir using black and white pencil, digitized with orange highlights. The faded edges and rounded corners of the framed illustrations resemble early television screens. With his use of cinematic perspective and dramatic lighting to create shadows, he increases tension and heightens suspense (Brown, 2013).

illustrations copyright © Peter Brown from Creepy Carrots!, written by Aaron Reynolds, Simon & Schuster, 2012

In the story, Jasper, a young rabbit, is convinced threatening carrots are stalking him. After a dizzying illustration that gives a nod to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Jasper cooks up an idea to thwart the carrots by fencing in the garden, thus corralling the carrots. He faces his fears, copes with the situation, and resolves the problem. This shows children that they have agency and are resourceful, while building their confidence.

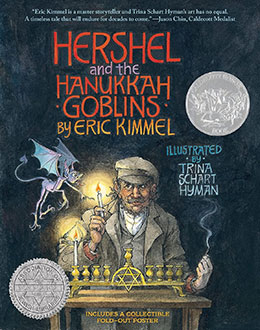

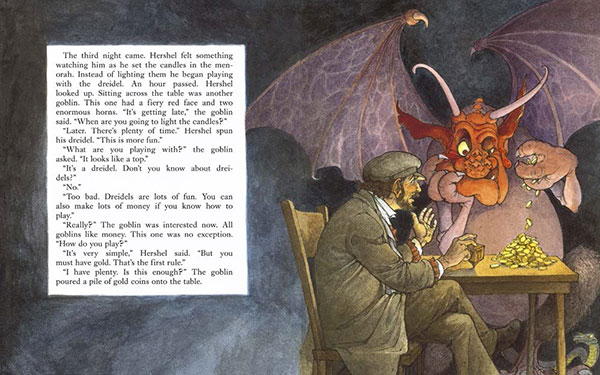

Peter Brown’s carrots and Maurice Sendak’s wild things are humorously scary. So are Trina Schart Hyman’s goblins in Eric Kimmel’s Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins that won a Caldecott Honor in 1990. All the goblins are wickedly funny except one. The King of the Goblins truly is scary looking. The goblins are haunting the synagogue, preventing the villagers from celebrating Hanukkah. But, Herschel of Ostropol volunteers to rid the synagogue of the goblins and outwits them all to save the holiday.

Peter Brown’s carrots and Maurice Sendak’s wild things are humorously scary. So are Trina Schart Hyman’s goblins in Eric Kimmel’s Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins that won a Caldecott Honor in 1990. All the goblins are wickedly funny except one. The King of the Goblins truly is scary looking. The goblins are haunting the synagogue, preventing the villagers from celebrating Hanukkah. But, Herschel of Ostropol volunteers to rid the synagogue of the goblins and outwits them all to save the holiday.

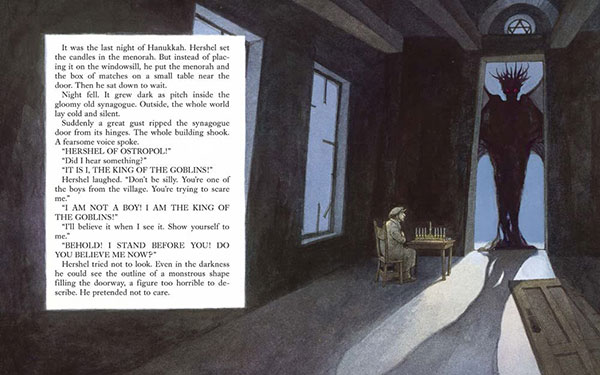

Hyman’s “india ink and acrylic paint” (ALSC, 2020, 125) illustrations are dark, depicting nighttime during winter. Her creative use of light illuminates the goblins and Herschel while the far corners of the room in which Herschel sits remain in shadows. The editor-in-chief of Holiday House said this of Hyman and her illustrations: “She loved mischief, but who thought she could do horror? Her ingenious art is terrifying and hilarious, too” (Maughan, 2014).

All the assorted goblins are illustrated colorfully in delightful detail. But, the King of the Goblins appears only as a silhouette with glowing red eyes, so large it fills the doorway. The reader never actually sees the goblin’s face, but rather sees Hershel’s terrified reaction. Frightened as he is, Herschel bravely and cleverly defeats this final goblin.

Hershel is not a child, but perhaps it is good for children to see that adults can be frightened and still be brave. Like Max and Jasper, Hershel faces his fears and, through his own resourcefulness, vanquishes them.

Herschel and the Hanukkah Goblins was republished in a 25th anniversary edition in 2014, and then again in 2022. It has become a staple story for the Hanukkah season. Kimmel wrote, “I wasn’t interested in explaining or defending the holiday. I wanted to find its spirit. My model was Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, which ignores the religious trappings of Christmas to focus on a universal message of compassion, joy, and goodwill” (Rogers, 2014). It also models bravery despite one’s fears.

Sendak, Brown, and Hyman’s illustrations might be scary to some, but not too scary. They use humor to diffuse what could be frightening to children. These books allow children to experience a little bit of fear from a safe distance, and then feel good about themselves for managing their emotions. As adults, we should not be afraid to share scary — appropriately scary — stories with children. Scary can be fun!

Picture Books Cited

Kimmel, E. (1990). Hershel and the Hanukkah goblins. Holiday House.

Reynolds, A. (2012). Creepy carrots! Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers.

Sendak, M. (1963). Where the wild things are. Harper & Row.

References

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). (2020). The Newbery and Caldecott Awards: A guide to the medal and honor books. American Library Association.

Arbuthnot, M. H. & Sutherland, Z. (1972). Children and books (4th ed.). Scott, Foresman.

August House. (n.d.). Why are scary stories so important?

Brown, P. (2013). The Creepy Carrots zone [Video].

Capstone. (n.d.). Scary books are good for kids.

Capstone. (2021). Why kids love scary books! bit.ly/45XaxBW

Lanes, S. (1998). The art of Maurice Sendak (2nd ed.). Abrams.

Kiriluk-Hill, R. (2013). 2013 Caldecott children’s book illustrator Peter Brown inspired by N.J. childhood.

Maughan, S. (2014). A haunting anniversary: Herschel and the Hanukkah goblins turn 25. Publishers Weekly.

Rogers, A. (2014). Putting books to work: Hershel and the Hanukkah goblins. ILA: Literacy Now.

Sendak, M. (1988). Caldecott & Co.: Notes on books and pictures. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.