With declining funding for arts education in schools1,2 and limited opportunities for school-sponsored class visits to art museums, Caldecott Award-winning picture books invite children to explore various media and styles of art deemed “distinguished.”3 Indeed, as professor of English and children’s literature specialist Philip Nel observes, “Good picture books are portable art galleries.”4

A number of Caldecott award books extend the art enrichment experience by introducing children to the lives and works of visual artists. Here, five picture books are considered, each featuring a significant creator.

Part 1: Dave the Potter, Wilson Bentley, Vasily Kandinsky, Frida Kahlo, and Jean-Michel Basquiat

Dave the Potter (1801?-187-?)5

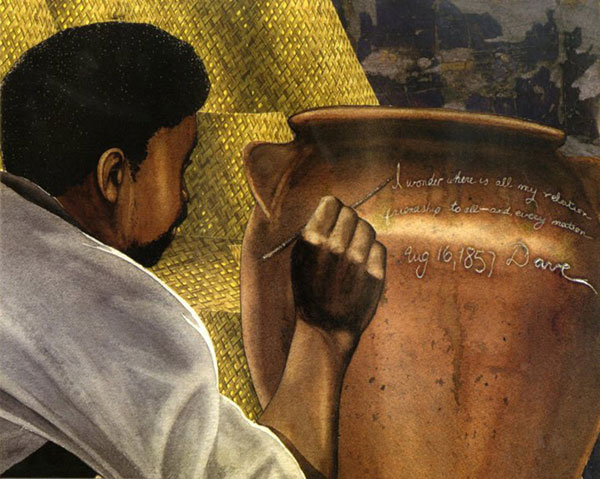

Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave, a 2011 Caldecott Honor book, calls attention to a remarkable 19th century potter. Born enslaved near Edgefield, South Carolina, Dave learned to read and write, likely by one of his first owners.6,7 This is noteworthy since, at that time, teaching a slave to write was illegal. When Dave was sold to an owner of a small pottery yard in 1832, he became an astute maker of stoneware pots, some with capacities from twenty-five to forty gallons.8 Much of Dave’s work is distinguished by his signature, the date, and sometimes an original poem.

Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave, a 2011 Caldecott Honor book, calls attention to a remarkable 19th century potter. Born enslaved near Edgefield, South Carolina, Dave learned to read and write, likely by one of his first owners.6,7 This is noteworthy since, at that time, teaching a slave to write was illegal. When Dave was sold to an owner of a small pottery yard in 1832, he became an astute maker of stoneware pots, some with capacities from twenty-five to forty gallons.8 Much of Dave’s work is distinguished by his signature, the date, and sometimes an original poem.

Historians refer to the artist as Dave, Dave the Slave, or Dave the Potter since slaves weren’t permitted to have family names.9,10 Upon the abolition of slavery, Dave chose the surname Drake, that of his first owner, and stayed in the Edgefield District until his death.11 Given the time and circumstances of his life, there are no known images of Dave, leaving Collier to find a model who he felt “reflected the spirit of Dave.”12 This spirit is further revealed in the book’s back matter, with a brief biography, including six additional poems, as well as author’s and illustrator’s notes.

Wilson Bentley (1865−1931)

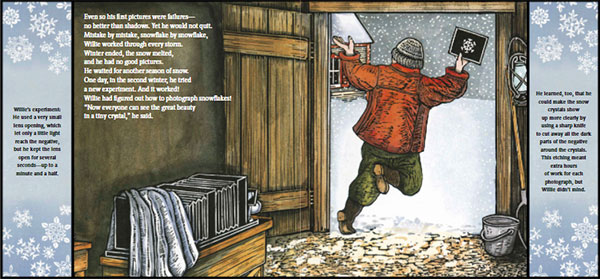

Using the medium of photography, Wilson Bentley is best known for his ground-breaking work documenting snowflakes. Snowflake Bentley, the 1999 Caldecott Medal book, introduces Willie, a boy intrigued by the natural world in Jericho, Vermont. Throughout his youth, Willie’s passion for snowflakes and his resolve to photograph them persuaded his parents to spend their savings on a sophisticated camera when the boy was seventeen.

Using the medium of photography, Wilson Bentley is best known for his ground-breaking work documenting snowflakes. Snowflake Bentley, the 1999 Caldecott Medal book, introduces Willie, a boy intrigued by the natural world in Jericho, Vermont. Throughout his youth, Willie’s passion for snowflakes and his resolve to photograph them persuaded his parents to spend their savings on a sophisticated camera when the boy was seventeen.

Jacqueline Briggs Martin’s text follows Willie throughout his life, painting him as self-motivated, with a curiosity not always understood by others, particularly those in his community. Mary Azarian’s woodcuts, hand-tinted with watercolors,13 meld realism with folk art. The prints are generally static and posed, much like early photographs. One marked exception is the double-page spread where Willie succeeds in capturing the first microphotograph ever taken of a snowflake and dashes out the door of the barn.

The sidebars complement the story, providing a broader view of Bentley’s life. While this convention is not uncommon today, Snowflake Bentley was among the first picture books to employ the feature. The text for the sidebars was not included in Martin’s manuscript; rather, the idea was proposed by visionary editor Ann Rider.14

Because Bentley was largely a self-taught scientist, many of his studies of various forms of water were not widely recognized in the scientific community15 until after his untimely death at age 66. In fact, Snow Crystals, published just weeks before he died, remains in print today. Martin’s and Azarian’s picture book homage to Wilson Bentley concludes, appropriately, with four photographs, one of the scientist-artist with his camera and three of his snowflake prints.

Vasily Kandinsky (1866−1944)

As Bentley was learning to capture snowflakes in microphotographs in Vermont, Vasily Kandinsky was also in his formative years, spent mostly in Russia. The 2015 Caldecott Honor book The Noisy Paint Box: The Colors and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art honors the life of a pioneer in the abstract art movement. Author Barb Rosenstock defines this book as historical fiction since “[t]he dialogue is imagined, although the events are true,”16 recounting the artist’s life in rich and evocative text.

As Bentley was learning to capture snowflakes in microphotographs in Vermont, Vasily Kandinsky was also in his formative years, spent mostly in Russia. The 2015 Caldecott Honor book The Noisy Paint Box: The Colors and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art honors the life of a pioneer in the abstract art movement. Author Barb Rosenstock defines this book as historical fiction since “[t]he dialogue is imagined, although the events are true,”16 recounting the artist’s life in rich and evocative text.

When readers meet young Vasya (the boy’s nickname), he is “learning to be a proper Russian boy.” In the opening spreads of the book, illustrator Mary GrandPré uses a cool blue palette and rigid lines to show Vasya, bored in his “well-off world” until an aunt gives him a small wooden paint box. Unexpectedly, Vasya hears sounds emerge when mixing and applying the paint. Biographers believe that he had synesthesia, in which “one sense triggers a different sense,”17 although at the time there were no tests to diagnose this genetic condition. Readers learn that as a young adult, Vasya also saw shapes and colors in his mind when attending an opera.

Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2014

After studying law and teaching in Moscow,18 30-year-old Vasya changed course, moving to Munich to pursue his passion for art. There, his work diverted from his teachers’ more traditional expectations as he painted original canvases of abstract shapes and vivid colors. GrandPré shows this transformation through a shift to warmer colors and curved lines. Painted words and flourishes representing sounds dance across the spreads as Vasya works in his studio and the public views his work. GrandPré explains she doesn’t attempt to copy Kandinsky’s style; rather, she strikes “a balance between honoring the artist and letting my own artistic expression come through.”19 Her style ranges from cartoon-like depictions of young Vasya to more realistic portrayals of an older Vasya, with expressionistic images of adults, all rendered with acrylic paint and paper collage.

In 1910, Kandinsky completes his first abstract painting “spark[ing] a revolution”20 among critics and artists. The story concludes at this point, with Kandinsky confident in his artistic direction. In his lifetime, he created hundreds of paintings21 and also wrote two books on art theory.22 Four of his paintings, from 1913 – 1922, are included with the Author’s Note.

Frida Kahlo (1907−1954)

Another innovative artist of the 20th century lived and worked on the other side of the world. Frida Kahlo, considered one of Mexico’s greatest artists, is best known for her surrealistic self-portraits. She explains, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”23 Kahlo faced physical challenges throughout her life. At age six, polio caused her right leg to wither. At age eighteen, she was seriously injured in a bus accident, fracturing her spine and pelvis. During her long convalescence, Kahlo began painting from her bed and developed her distinctive, often unsettling, style.

Another innovative artist of the 20th century lived and worked on the other side of the world. Frida Kahlo, considered one of Mexico’s greatest artists, is best known for her surrealistic self-portraits. She explains, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”23 Kahlo faced physical challenges throughout her life. At age six, polio caused her right leg to wither. At age eighteen, she was seriously injured in a bus accident, fracturing her spine and pelvis. During her long convalescence, Kahlo began painting from her bed and developed her distinctive, often unsettling, style.

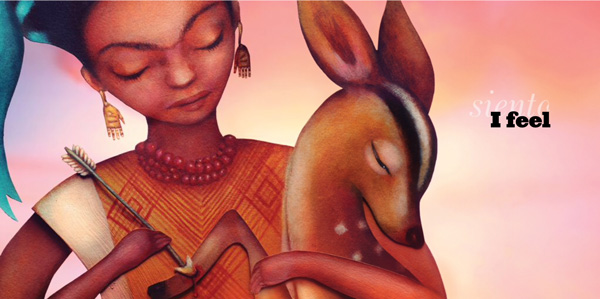

In the 2015 Caldecott Honor book Viva Frida, author-illustrator Yuyi Morales offers a loving tribute to the artist. The spare bilingual text affirms discovery and play, dreams and creativity. Morales’ remarkable surrealistic illustrations draw readers into a wondrous world. The initial series of stunning spreads include hand-crafted three-dimensional puppets made from steel, polymer clay, and wool;24 these are positioned on colorful sets, then photographed by Tim O’Meara. Perspectives shift in each double-page, full bleed spread. During a dream sequence, the medium changes to ethereal acrylic paintings in pastel colors as Frida flies across the pages, free from pain and worries.

The artwork expands upon the text to reveal details of Kahlo’s life. Readers see iconic images from her paintings: a pet monkey, dog, parrot, and hummingbird. La Casa Azul, where Kahlo lived much of her life, and husband Diego Rivera also make appearances. The spread of Frida with an injured deer is a reference to Kahlo’s painting “The Wounded Deer.” A bilingual author’s note sheds more light on the artist, as well as Morales’ changing perception of her work. A four-minute wordless video documents Morales’ meticulous process of building the puppets, costumes, and sets to provide insight into the creation of the illustrations of this noteworthy biography.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960−1988)

Later in the 20th century, groundbreaking artist Jean-Michel Basquiat captured the attention of the New York City art scene and well beyond in his short, driven life. In the 2017 Caldecott Medal book Radiant Child, author-illustrator John Steptoe brings Basquiat’s story to a young audience.

Later in the 20th century, groundbreaking artist Jean-Michel Basquiat captured the attention of the New York City art scene and well beyond in his short, driven life. In the 2017 Caldecott Medal book Radiant Child, author-illustrator John Steptoe brings Basquiat’s story to a young audience.

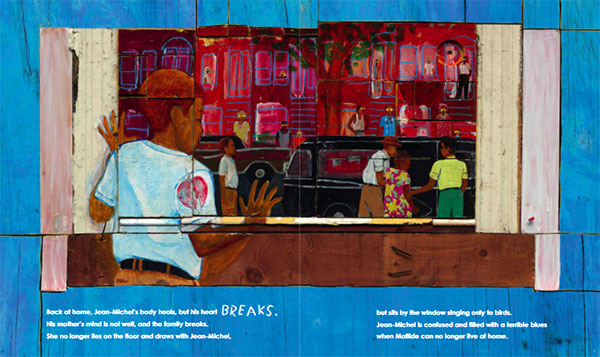

Born in Brooklyn to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, Basquiat began drawing at an early age, finding a kindred spirit with his mother Mathilde. Basquiat’s reflected, “[M]y mother gave me all the primary things. The art came from her.”25 This quote led Steptoe to “create a story about love between a mother and her son.”26 To that end, the author-illustrator focuses on key moments in their relationship: drawing together on the floor, visiting art museums, poring over a copy of Gray’s Anatomy when the seven-year-old was recovering from being hit by a car. The most poignant scene shows Mathilde leaving the family later that year, struggling with mental illness.

The story moves forward with Basquiat’s determination to make art, leaving home at seventeen to hit the streets of the Lower East Side, finding friends willing to give him space to sleep and make art. His co-created SAMO© graffiti art evolves into solo unnerving, neo-expressionist27 paintings, drawings, and collages that ultimately take the art world by storm. As the book concludes, Basquiat’s success is linked to his mother who holds “the place of honor…, a queen on a throne.” The final double-page spread is dominated by a Basquiat-style photo collage, yet on the far right rests a narrow, painted panel of the adult artist and his mother.

Basquiat’s life was cut short when he died of a drug overdose at age twenty-seven. While the artist’s tribulations were known by many, Steptoe focuses on the artist’s unyielding motivation to find affirmation and success as a “famous artist.” Steptoe was compelled to undertake the book because “you cannot discuss modern art without Basquiat.”28 Addressing his choice to write a children’s book about a “controversial figure,” Steptoe explains, “…we live in a complicated world, and children’s books can open spaces for young people to learn lessons that help prepare them for it.”29

Steptoe’s expressionist illustrations, mixed media collage with acrylic paint and oil pastels on wood,30,31 emulate Basquiat’s work, none of which is included in the book. For the textured canvases, Steptoe repurposed discarded wood from various locations in New York City. The wood also provides a natural frame for the mostly double-page spreads. The illustrator includes many of the motifs common in Basquiat’s work: eyes, cars, skulls, bones, and his ubiquitous crowns. The blue endpapers are filled with these and other motifs and words, drawn and painted in white. Steptoe’s biography honors the “Radiant Child” whose work continues to influence contemporary artists and remains relevant today.

The artists highlighted in these picture book biographies left a wide-ranging body of work that is still appreciated and studied. While confronting many hurdles, from enslavement and public disdain, to physical illness and mental health challenges, the artists remained devoted to their calling. These Caldecott-winning biographies share their enduring contributions with a new generation of readers and aspiring artists.

Works Cited

Bentley, W. A., and W. J. Humphreys. Snow Crystals. New York: Dover, 1962.

Hill, Laban Carrick. Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave. Illustrated by Bryan Collier. New York: Little, Brown, 2010.

Martin, Jacqueline Briggs. Snowflake Bentley. Illustrated by Mary Azarian. Boston: Houghton, 1998.

Morales, Yuyi. Viva Frida. Photographed by Tim O’Meara. Boston: Roaring Brook, 2014.

— – . “Making Viva Frida,” Yuyi Morales. 4 September 2014. Video, 3:56. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mu8mZLmewI.

Rosenstock, Barb. The Noisy Paint Box: The Colors and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art. Illustrated by Mary GrandPré. New York: Knopf, 2014.

Steptoe, Javaka. Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. New York: Little, Brown, 2016.

Notes

- Kevin Tutt, “U.S. Arts Education Requirements,” Arts Education Policy Review 115, no. 3 (July 2014): 93 – 97, doi:10.1080/10632913.2014.914394.

- “State of the Arts,” Educational Leadership 70, no. 5 (February 2013): 8.

- Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), Randolph Caldecott Medal Committee Manual. ([Chicago, Ill.: The Association], 2009): 10, accessed 17 January 2021.

- Philip Nel, “A Manifesto for Children’s Literature; or, Reading Harold as a Teenager,” Nine Kinds of Pie (blog), 28 April 2013, accessed 17 January 2021.

- SCIWAY: South Carolina’s Information Highway, “Dave the Potter — Pottersville, Edgefield County, South Carolina,” SCIWAY, 2013, accessed 17 January 2021.

- SCIWAY.

- Tom Mack, “Dave the Potter,” University of South Carolina – Aiken, October 5, 1999.

- Mack.

- SCIWAY, “Dave the Potter.”

- Laban Carrick Hill, Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave, illustrated by Bryan Collier (New York: Little, Brown, 2010).

- SCIWAY, “Dave the Potter.”

- Hill, Dave the Potter.

- Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), The Newbery & Caldecott Awards: A Guide to the Medal and Honor Books (Chicago: American Library Association, 2017), 110.

- Jacqueline Briggs Martin, conversation with author, February 1, 2020.

- Duncan C. Blanchard, “The Snowflake Man,” Weatherwise 23, no. 6 (1970): 260 – 269.

- Barb Rosenstock, The Noisy Paint Box: The Colors and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art, illustrated by Mary GrandPré (New York: Knopf, 2014).

- Rosenstock.

- “The Biography,” Kandinsky, wassilykandinsky.net, accessed 17 January 2021.

- Betsy Bird, “2019 Sydney Taylor Book Award Blog Tour: Through the Window — Talking with Barb Rosenstock and Mary GrandPré,” A Fuse #8 Production (blog), 10 February 2019.

- Rosenstock, The Noisy Paint Box.

- “The Biography,” Kandinsky.

- “Wassily Kandinsky and his Paintings,” Wassily Kandinsky: Biography, Paintings, and Quotes, Wassily-Kandinsky.org, accessed 17 January 2021.

- “Frida Kahlo Quotes,” Frida Kahlo: Paintings, Biography, Quotes, FridaKahlo.org, accessed 17 January 2021.

- Yuyi Morales. Viva Frida, photographed by Tim O’Meara (Boston: Roaring Brook, 2014).

- Javaka Steptoe, “Caldecott Medal Acceptance,” Horn Book Magazine 93, no. 4 (2017): 66.

- Steptoe, 66.

- “Chronology,” Jean-Paul Basquiat, The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, accessed 17 January 2021.

- Steptoe, “Caldecott Medal Acceptance,” 66.

- Steptoe, 67.

- ALSC, The Newbery & Caldecott Awards, 92.

- “The Magical and Messy Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Conversation with Javaka Steptoe,” School Library Journal Digitized Edition, School Library Journal, 20 August 2016.

Bibliography

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). The Newbery & Caldecott Awards: A Guide to the Medal and Honor Books. Chicago: American Library Association, 2017.

— – . Randolph Caldecott Medal Committee Manual. [Chicago, Ill.: The Association], 2009. http://www.ala.org/alsc/sites/ala.org.alsc/files/content/awardsgrants/bookmedia/caldecottmedal/caldecottcomm/caldecott_manual_august2020_current%20on%20website%20%281%29.pdf.

“The Biography.” Kandinsky. wassilykandinsky.net. Accessed 17 January 2021. https://www.wassilykandinsky.net.

Bird, Betsy Bird. “2019 Sydney Taylor Book Award Blog Tour: Through the Window – Talking with Barb Rosenstock and Mary GrandPré.” A Fuse #8 Production (blog). 10 February 2019. http://blogs.slj.com/afuse8production/2019/02/10/2019-sydney-taylor-book-award-blog-tour-through-the-window-talking-with-barb-rosenstock-and-mary-grandpre/.

Blanchard, Duncan C. “The Snowflake Man.” Weatherwise 23, no. 6 (1970): 260 – 269. https://snowflakebentley.com/snowflake-man-bio.

“Chronology.” Jean-Paul Basquiat. The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Accessed 17 January 2021. http://www.basquiat.com/artist.htm.

“Frida Kahlo Quotes.” Frida Kahlo: Paintings, Biography, Quotes. FridaKahlo.org. Accessed 17 January 2021. https://www.fridakahlo.org/frida-kahlo-quotes.jsp.

Hill, Laban Carrick. Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave. Illustrated by Bryan Collier. New York: Little, Brown, 2010.

Mack, Tom. “Dave the Potter.” University of South Carolina – Aiken. October 5, 1999. https://polisci.usca.edu/aasc/davepotter.htm.

“The Magical and Messy Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Conversation with Javaka Steptoe.” School Library Journal Digitized Edition. School Library Journal, 20 August 2016. https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=the-magical-and-messy-art-of-jean-michel-basquiat-a-conversation-with-javaka-steptoe.

Morales, Yuyi. Viva Frida. Photographed by Tim O’Meara. Boston: Roaring Brook, 2014.

Nel, Philip. “A Manifesto for Children’s Literature; or, Reading Harold as a Teenager.” Nine Kinds of Pie (blog). 28 April 2013. https://philnel.com/2013/04/28/manifesto/.

Rosenstock, Barb. The Noisy Paint Box: The Colors and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art. Illustrated by Mary GrandPré. New York: Knopf, 2014.

SCIWAY: South Carolina’s Information Highway. “Dave the Potter — Pottersville, Edgefield County, South Carolina.” SCIWAY. SCIWAY, 2013. http://www.sciway.net/afam/dave-slave-potter.html.

“State of the Arts.” Educational Leadership 70, no. 5 (February 2013): 8.

Steptoe, Javaka. “Caldecott Medal Acceptance.” Horn Book Magazine 93, no. 4 (2017): 64 – 68.

Tutt, Kevin. “U.S. Arts Education Requirements.” Arts Education Policy Review 115, no. 3 (July 2014): 93 – 97. doi:10.1080/10632913.2014.914394.

“Wassily Kandinsky and his Paintings.” Wassily Kandinsky: Biography, Paintings, and Quotes. Wassily-Kandinsky.org. Accessed 17 January 2021. https://www.wassily-kandinsky.org.