When considering picture book biographies of visual artists, one cannot overlook the three illustrators who have garnered Caldecott Honors for their autobiographical works.

Part 2: Bill Peet, Uri Shulevitz, and Peter Sís2

Bill Peet (né William Bartlett Peed)1 (1915 — 2002)

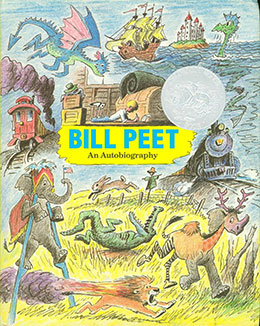

In Bill Peet: An Autobiography, the author-illustrator recounts a life guided by his passion for art. As a child in Indianapolis, when not romping in the woods or playing in a creek near his home, Bill Peet was drawing. “I drew for hours at a time just for the fun of it, and yet I was hoping to find some practical reason to draw for the rest of my life.”2 His stable home life with his two brothers, mother, and grandmother turned chaotic when his absent and abusive father returned in 1928 and his grandmother died shortly afterwards. For the next few years, the family remained in the city but moved often, kept poor during the Great Depression by his spendthrift father.

In Bill Peet: An Autobiography, the author-illustrator recounts a life guided by his passion for art. As a child in Indianapolis, when not romping in the woods or playing in a creek near his home, Bill Peet was drawing. “I drew for hours at a time just for the fun of it, and yet I was hoping to find some practical reason to draw for the rest of my life.”2 His stable home life with his two brothers, mother, and grandmother turned chaotic when his absent and abusive father returned in 1928 and his grandmother died shortly afterwards. For the next few years, the family remained in the city but moved often, kept poor during the Great Depression by his spendthrift father.

Peet struggled academically in high school until he focused on art, which led to a scholarship to the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis. The young man left after three years in the hopes of establishing himself as an artist. In 1937, he applied for and was accepted into a one-month “tryout” in Los Angeles for Walt Disney Studios. While Peet “was never interested in any kind of cartooning….it was no time to be choosy”3 in an uncertain economy. He passed the grueling trial and began what was to become a 27-year career, primarily as a sketch artist and story developer. He worked on such classic animated films as Fantasia, Alice in Wonderland, Sleeping Beauty, and 101 Dalmatians.

Working with cantankerous creative personalities was trying and Peet found himself “much more interested in illustrating story books, which was my very first boyhood ambition.”4 In the late 1940s through the 1950s, Peet dreamed up dozens of stories, many shared with his sons at bedtime and developed as sketches, but he struggled writing engaging text. Finally, the Golden Book that Peet developed from the 1959 Disney movie Goliath II proved to be a breakthrough, giving him confidence to return to his many tablets filled with ideas. He published five books with Houghton Mifflin before leaving Walt Disney Studios in 1964 to devote his time to writing and illustrating He ended his successful second career with 35 picture books.

Bill Peet, HMH Books for Young Readers, 1989

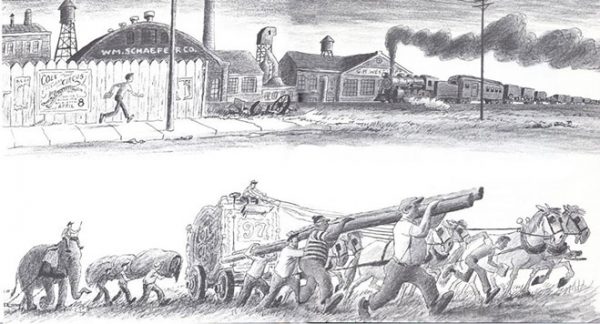

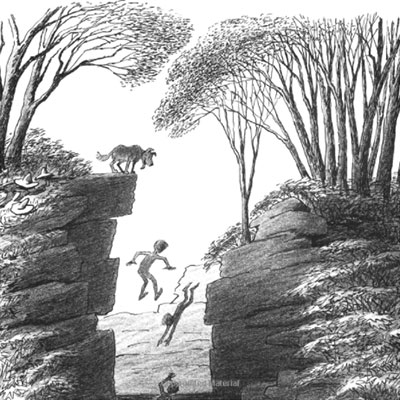

Peet presents his life story as an unbroken narrative in 190 pages, copiously illustrated with energetic black and white drawings rendered in pencil5 and pen and ink in Peet’s familiar cartoon style. Each single- or double-page spread devotes as much space to illustrations as to text, with dynamic page designs that vary throughout the book.

That this hefty tome received a 1990 Caldecott Honor may seem surprising, as the Caldecott Award recognizes “most distinguished American picture book for children.”6 Picture books are typically 32 pages, although they can range in length from 24 to 48 pages or longer.7 However, each Caldecott Award Committee establishes which books meet the definition: “[A]s distinguished from other books with illustrations, [a picture book for children] is one that essentially provides the child with a visual experience. A picture book has a collective unity of storyline, theme, or concept, developed through the series of pictures of which the book is comprised.”8 Further, “Children are defined as persons of ages up to and including fourteen.”9 Committee decisions regarding a book’s eligibility are made with careful consideration and deliberation of award definitions and criteria in tandem with picture book presentation and content. The drawings in Peet’s autobiography complement and expand the text, depicting the people, animals, landscapes, and imaginative creatures that define Peet’s life as a professional artist.

Bill Peet, HMH Books for Young Readers, 1989

Uri Shulevitz (1935 — )

Across the globe in Warsaw, Poland, another boy was destined to be an artist. When Uri Shulevitz arrived home from the hospital, not yet named, his father saw him studying the flowered wallpaper from his crib. His father pronounced that “‘His name should be Uri, after the biblical Uri…the first artist of the Bible.’ Mother agreed.”10 By age three, Uri was drawing on the apartment walls; later, he drew wherever he could, including the margins of his father’s newspapers.11

Across the globe in Warsaw, Poland, another boy was destined to be an artist. When Uri Shulevitz arrived home from the hospital, not yet named, his father saw him studying the flowered wallpaper from his crib. His father pronounced that “‘His name should be Uri, after the biblical Uri…the first artist of the Bible.’ Mother agreed.”10 By age three, Uri was drawing on the apartment walls; later, he drew wherever he could, including the margins of his father’s newspapers.11

His childhood was far from idyllic, however. When Shulevitz was four, the Warsaw blitz of 1939 damaged the family’s apartment building. In desperation, the boy and his mother escaped Poland to join his father, who was waiting for them in the Soviet Union. At that time, they didn’t realize they would be refugees for the next ten years, in search of a permanent home in a new country.

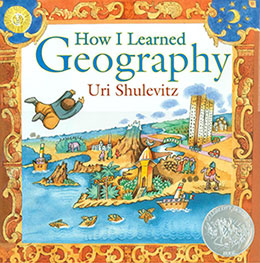

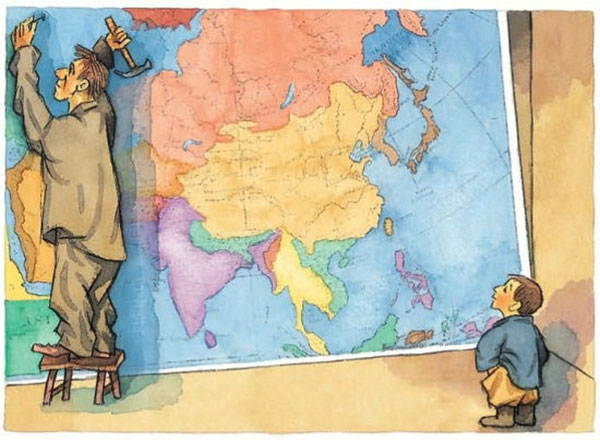

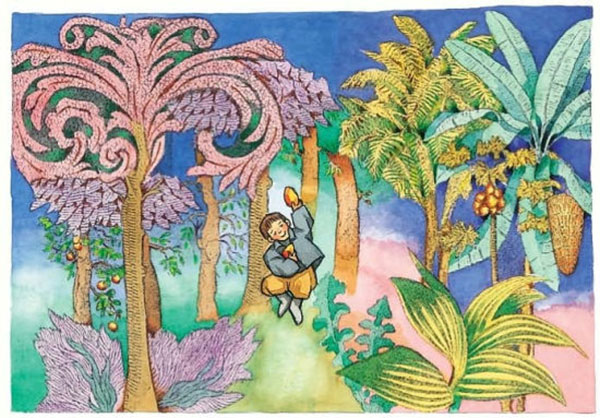

How I Learned Geography, Uri Shulevitz, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008

How I Learned Geography, a 2008 Caldecott Honor book, is a slice-of-life autobiography in which Shulevitz retells a poignant story from the family’s early years in the city of Turkestan in what is now Kazakhstan, when he was four or five. As refugees, the family shared a small room with another couple, slept on the floor, and had few belongings. “Worst of all: food was scarce.” One day, his father leaves for the bazaar to buy bread and returns late in the evening with only a large, rolled map in his arms. The family goes to bed hungry. When his father hangs the map the next day, it covers a wall: “Our cheerless room was flooded with color.” The boy treasures the map, copying it on scraps of paper whenever he can. He studies the unusual place names and dreams of exploring the world. “And so I spent enchanted hours far, far from our hunger and misery.”

In a cartoon style, Shulevitz infuses his collage, pen and ink, and watercolor12 illustrations in golds and blues. In the spreads depicting the boy’s imaginative travels, Shulevitz incorporates colors from the map, using abundant textures.

How I Learned Geography, Uri Shulevitz, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008

Despite a rootless childhood with many tribulations, Shulevitz’s parents encouraged and valued his artistic endeavors.13 Once the family settled in Israel in 1949, the teen studied at the Art Institute of Tel Aviv. At 24, Shulevitz moved to New York City and began illustrating books for a Hebrew publisher. His work caught the eye of renowned editor Susan Hirschman, who encouraged him to write a children’s book. With her guidance, Shulevitz published his first book, The Moon in My Room, in 1963, four years after arriving in the United States. His career includes a 1969 Caldecott Medal for Arthur Ransome’s The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship and Caldecott Honors for The Treasure in 1980 and for Snow in 1999. In addition to over 40 picture books, his literary credits include an illustrated memoir for young people, Chance: Escape from the Holocaust, which chronicles his family’s journeys during and after World War II. While Shulevitz credits his family’s survival to chance, his enduring success as an author-illustrator rests on his “love of stories”14 and his effort “to keep a fresh approach to [his] art.”15

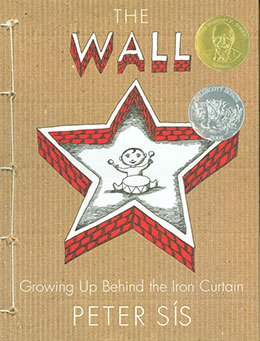

Peter Sís (1949 — )

Born in Brno, Czechoslovakia, in postwar Europe, author-illustrator Peter Sís grew up under Communist rule. Undaunted by a restrictive government, his parents fostered the boy’s interest in art at a young age.

Born in Brno, Czechoslovakia, in postwar Europe, author-illustrator Peter Sís grew up under Communist rule. Undaunted by a restrictive government, his parents fostered the boy’s interest in art at a young age.

His mother, an artist, kept him supplied with paper and pencils16 once he started drawing at age four or five.17 His father, a filmmaker, raised his son “with a desire to be an artist and to be successful.”18 However, as Sís reveals in his autobiographical work The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain, expressing a creative spirit in a repressive country is challenging and sometimes dangerous.

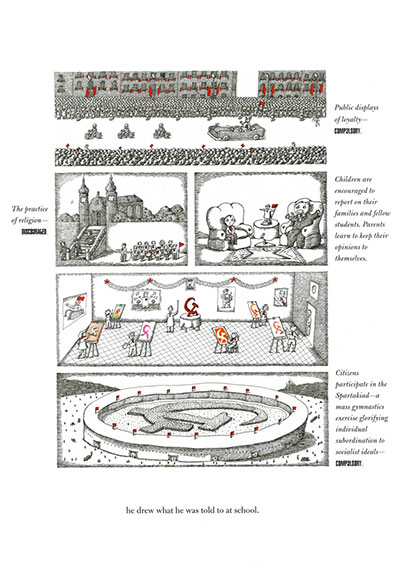

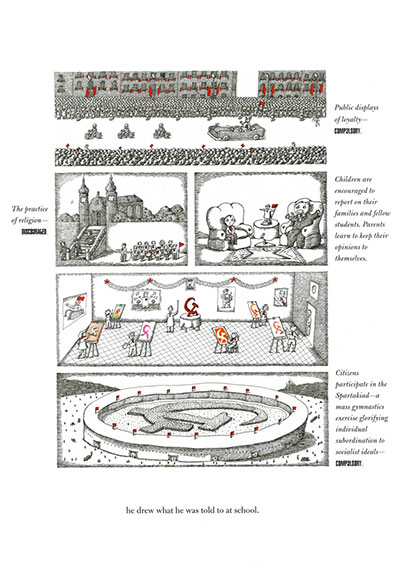

Told in the third person, Sís follows a boy “who loved to draw.” As he grows older, he begins to realize that freedom is constricted, actions are monitored, and art is censored in this “monotone and monolithic society.”19 In 1968, a progressive Czech government is short-lived, quashed by troops from the Soviet Union. In response, the artist and others like him are stealthily rebellious. Finally, seeking liberation, the artist soars over a security fence, then a metaphorical wall, on a flying bicycle that is lifted with wings magically constructed from his paintings.

Sís’s 2008 Caldecott Honor book is multilayered. A simple sentence or phrase appears on the bottom of the single-page spreads. The deeper context is shown in minutely detailed illustrations, displayed either as multiple panels or single large images. Italicized text along the sides of the illustrations describes the insidious actions of the government and its informants. Three double-page spreads show “the time of brainwashing,” a color-filled Spring season of hope, and a deadly post-concert “mêlée” with police. The double-page spreads at the end of the book follow the artist’s journey to freedom.

Embedded in the narrative are three “From My Journals” spreads, with Sís’s personal reflections from 1954 – 1977. He explains that entries are not from actual journals but are “more like memories from my childhood drawings,”20 added to the book upon the urging of his astute editor Frances Foster. Readers familiar with Sís’s work will recognize the first entry, a reference to his father’s trip to China “to make a film.” Sís reconstructs the story of the filmmaker’s narrow escape from the collapse of a mountain wall and his months long trek through Tibet in the 1999 Caldecott Honor book Tibet Through the Red Box, “the ultimate tribute”21 to his father.

To create his pointillist and surrealistic illustrations,22 Sís uses “fine marker plus read ink, pen and ink with wash, [and] watercolors”23 on “very, very cheap industrial paper” in an attempt to “keep it very raw.”24 Most of the illustrations are black and white, with strategic daubs of red and subversive splashes of colors. The cover gives the appearance of corrugated carboard, the book hand-bound with string.

The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain,

Peter Sis, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007

The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain,

Peter Sis, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007

Much of the story mirrors Sís’s life, with a couple of notable exceptions. Interestingly, he and his family were traveling in Europe when the Soviet tanks and soldiers arrived in Prague in 1968. Later, in 1982, Sís came to the United States as an animator. When the project fell through and he was called back to Czechoslovakia, he defected; thus, he didn’t witness the 1989 collapse of the Communist régime in his native country, when The Wall concludes.

The animator’s transition to children’s book illustrator occurred when an acquaintance sent copies of Sís’s work to Maurice Sendak. While Sís hadn’t considered illustrating children’s books, Sendak saw great potential in the artist and became a mentor. To date, Sís has illustrated over 40 books in the United States, 28 of which he also wrote. In addition to the two Caldecott Honors already noted, he received a third in 1997 for Starry Messenger, a biography of Galileo Galilei. Beyond Sís’s success as an author-illustrator, he has published editorial drawings and undertaken public art projects, such as murals, mosaics, and tapestries.25,26 Indeed, like the young artist in The Wall, Sís’s creativity cannot be restrained.

In their autobiographical works, Bill Peet, Uri Shulevitz, and Peter Sís share how they began drawing as children and continued to pursue their art into adulthood, despite hardships along the way. Through personal stories, the author-illustrators reveal their drive to create and their tenacity to continue their artistic endeavors. These books encourage children to follow their passions, while reminding adults to provide support to young people as they explore and develop their talents.

Books Cited

Bentley, W. A., and W. J. Humphreys. Snow Crystals. New York: Dover, 1962.

Peet, Bill. Bill Peet: An Autobiography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

Peet, Bill. Walt Disney’s Goliath II. New York: Golden Press, 1959.

Ransome, Arthur. The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship. Illustrated by Uri Shulevitz. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1968.

Shulevitz, Uri. Chance: Escape from the Holocaust. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2020.

Shulevitz, Uri. How I Learned Geography. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2008.

Shulevitz, Uri. The Moon in My Room. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

Shulevitz, Uri. The Treasure. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1979.

Shulevitz, Uri. Snow. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1998.

Sís, Peter. Starry Messenger: Galileo Galilei. New York: Frances Foster Books/ Farrar Straus Giroux, 1996.

Sís, Peter. Tibet Through the Red Box. New York: Frances Foster Books/Farrar Straus Giroux, 1998.

Sís, Peter. The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain. New York: Frances Foster Books/Farrar Straus Giroux, 2007.

Notes

- Eric P. Nash, “Bill Peet, 87, Disney Artist and Children’s Book Author,” New York Times, 18 May 2002.

- Bill Peet, Bill Peet: An Autobiography (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989), 6.

- Peet, 71.

- Peet, 137.

- Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), The Newbery & Caldecott Awards: A Guide to the Medal and Honor Books (Chicago: American Library Association, 2017), 118.

- Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), Randolph Caldecott Medal Committee Manual ([Chicago, Ill.: The Association], 2009): 10, accessed 12 February 2021.

- Christine Van Zandt, “Ask an Editor: Why are Picture Books 32 Pages?,” Kite Tales: A Blog Published for the SCBWI Tri-Regions of Southern California, Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators-Los Angeles, 8 June 2016.

- ALSC, Randolph Caldecott Medal Committee Manual, 10.

- ALSC, Randolph Caldecott Medal Committee Manual, 10.

- Uri Shulevitz, Chance: Escape from the Holocaust (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2020), 17.

- Shulevitz, Chance, 18.

- ALSC, The Newbery & Caldecott Awards, 101.

- Ingrid Roper, “On Memoir and Memories,” Publishers Weekly 267, no. 29 (July 20, 2020): 29.

- Sharon Korbeck Verbeten, “A Storied Career: At 70, Uri Shulevitz Isn’t Slowing Down,” Children and Libraries: The Journal of the Association for Library Service to Children 3, no. 2 (Summer/Fall2005 2005): 52.

- Allen Raymond, “Uri Shulevitz: ‘For Children of All Ages,’” Teaching Pre K‑8 22, no. 4 (January 1992): 40.

- Peter Sís, “Peter Sís: Acceptance Speech by Peter Sís,” IBBY: International Board on Books for Young People, International Board on Books for Young People, 25 August 2012.

- Anthony Mason and Martha Teichner, “The Story of Artist Peter Sis, CBS.” CBS News Sunday Morning. Viacom Internet Services Inc., 5 January 2001.

- Steven Heller, “Peter Sís, Children’s Book Author and Illustrator,” Print 58, no. 3 (May 2004): 30.

- Mason “The Story of Artist Peter Sís, CBS.”

- Cyndi Giorgis and Nancy J. Johnson, “Talking with Peter Sís,” Book Links 17, no. 6 (July 2008): 14.

- Heller, “Peter Sís,” 155.

- Will Hillenbrand, “Dreams from Nightmares: An Interview with Peter Sís,” The Artist’s Magazine, July-August 2015, Gale In Context: High School.

- ALSC, The Newbery & Caldecott Awards, 102.

- Giorgis, “Talking with Peter Sís,” 15.

- Heller, “Peter Sís,” 155.

- “Peter Sís Press Release: The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art Presents: The Picture Book Odysseys of Peter Sís,” The Carle, The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, 30 May 2019.

Bibliography

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). The Newbery & Caldecott Awards: A Guide to the Medal and Honor Books. Chicago: American Library Association, 2017.

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). Randolph Caldecott Medal Committee Manual. [Chicago, Ill.: The Association], 2009.

Giorgis, Cyndi, and Nancy J. Johnson. “Talking with Peter Sís.” Book Links 17, no. 6 (July 2008): 13 – 16.

Heller, Steven. “Peter Sís, Children’s Book Author and Illustrator.” Print 58, no. 3 (May 2004): 30 – 162.

Hillenbrand, Will. “Dreams from Nightmares: An Interview with Peter Sís.” The Artist’s Magazine, July-August 2015, 44+. Gale In Context: High School.

Mason, Anthony, and Martha Teichner. “The Story of Artist Peter Sis, CBS.” CBS News Sunday Morning. Viacom Internet Services Inc., 5 January 2001. 5 January 2001.

Nash, Eric P. “Bill Peet, 87, Disney Artist and Children’s Book Author.” New York Times, 18 May 2002.

Peet, Bill. Bill Peet: An Autobiography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

“Peter Sís Press Release: The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art Presents: The Picture Book Odysseys of Peter Sís.” The Carle. The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, 30 May 2019.

Raymond, Allen. “Uri Shulevitz: ‘For Children of All Ages.’” Teaching Pre K‑8 22, no. 4 (January 1992): 38 – 40.

Roper, Ingrid. “On Memoir and Memories.” Publishers Weekly 267, no. 29 (July 20, 2020): 28 – 29.

Shulevitz, Uri. Chance: Escape from the Holocaust. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2020.

Sís, Peter. “Peter Sís: Acceptance Speech by Peter Sís.” IBBY: International Board on Books for Young People. International Board on Books for Young People, 25 August 2012.

Van Zandt, Christine. “Ask an Editor: Why are Picture Books 32 Pages?” Kite Tales: A Blog Published for the SCBWI Tri-Regions of Southern California. Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators-Los Angeles, 8 June 2016.

Verbeten, Sharon Korbeck. “A Storied Career: At 70, Uri Shulevitz Isn’t Slowing Down.” Children and Libraries: The Journal of the Association for Library Service to Children 3, no. 2 (Summer/Fall 2005): 52 – 53.

I retired from a public school library 5 years ago. All 3 of these brought back fond memories. My favorite was Bill Peet’s biography. Even the most reluctant reader loved it!!