For the past two years my husband and I have had the good fortune to spend the waning days of summer in Door County, Wisconsin. There we have discovered a vibrant arts community. A bounty of theatre, music, and fine arts is there for the picking.

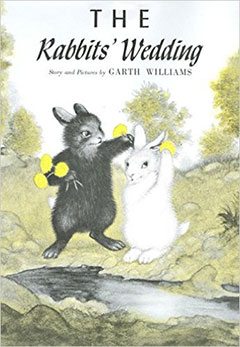

This year, as I scanned the possibilities for our visit, I was particularly interested in the Peninsula Players’ Midwest première of a new play by Kenneth Jones called Alabama Story. The play comes from actual events which occurred in Alabama in 1959. Based on the American Library Association’s recommendation, State Librarian Emily Wheelock Reed purchased copies of the picture book, The Rabbits’ Wedding by Garth Williams, for state libraries. The Rabbits’ Wedding concerns a black rabbit and a white rabbit who marry. Though Williams, an artist, chose the colors of the rabbits for the contrast they would provide in his illustrations, they became symbolic of much more when segregationist Senator E.O. Eddins demanded that the book be removed from all state library shelves. Eddins believed that the book promoted the mixing of races. Alabama Story tells this story of censorship, juxtaposed with the story of a biracial relationship.

This year, as I scanned the possibilities for our visit, I was particularly interested in the Peninsula Players’ Midwest première of a new play by Kenneth Jones called Alabama Story. The play comes from actual events which occurred in Alabama in 1959. Based on the American Library Association’s recommendation, State Librarian Emily Wheelock Reed purchased copies of the picture book, The Rabbits’ Wedding by Garth Williams, for state libraries. The Rabbits’ Wedding concerns a black rabbit and a white rabbit who marry. Though Williams, an artist, chose the colors of the rabbits for the contrast they would provide in his illustrations, they became symbolic of much more when segregationist Senator E.O. Eddins demanded that the book be removed from all state library shelves. Eddins believed that the book promoted the mixing of races. Alabama Story tells this story of censorship, juxtaposed with the story of a biracial relationship.

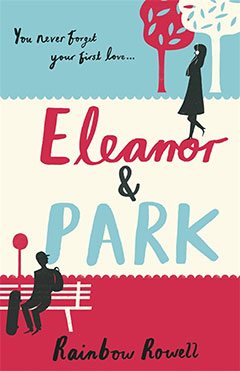

My husband and I both had tears in our eyes several times throughout the August 31st performance of Alabama Story. Censorship was something we know intimately. Though Alabama Story takes place in 1959, it could have taken place in 2013 in Anoka, Minnesota, with a teen book entitled Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell. My high school Library Media Specialist colleagues and I had planned a district-wide community read for the summer of 2013. Based on our own reading of the book, and based on the fact that the book had received starred reviews across the board and was on many “best” lists for 2013, we chose Eleanor & Park as the book for the summer program. All students who volunteered to participate received a free copy of the book. Rainbow Rowell agreed to visit in the fall for a day of follow-up with the participants. Shortly after the books were handed out, just prior to our summer break, parents of one of the participants, along with the Parents’ Action League (deemed a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center) registered a challenge against the book. Their complaint had to do with the language that they deemed inappropriate in the book and with the sexual content in the book. They demanded that the parents of all participants be informed that their child had been “exposed” to the book (they were not), that Rainbow Rowell’s visit be cancelled (it was), that copies of the book be removed from the shelves of all district schools (they were not), that our selection policy be rewritten (it was), and that the Library Media Specialists be disciplined (we received a letter). The story gained national attention in the late summer and fall of 2013.

My husband and I both had tears in our eyes several times throughout the August 31st performance of Alabama Story. Censorship was something we know intimately. Though Alabama Story takes place in 1959, it could have taken place in 2013 in Anoka, Minnesota, with a teen book entitled Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell. My high school Library Media Specialist colleagues and I had planned a district-wide community read for the summer of 2013. Based on our own reading of the book, and based on the fact that the book had received starred reviews across the board and was on many “best” lists for 2013, we chose Eleanor & Park as the book for the summer program. All students who volunteered to participate received a free copy of the book. Rainbow Rowell agreed to visit in the fall for a day of follow-up with the participants. Shortly after the books were handed out, just prior to our summer break, parents of one of the participants, along with the Parents’ Action League (deemed a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center) registered a challenge against the book. Their complaint had to do with the language that they deemed inappropriate in the book and with the sexual content in the book. They demanded that the parents of all participants be informed that their child had been “exposed” to the book (they were not), that Rainbow Rowell’s visit be cancelled (it was), that copies of the book be removed from the shelves of all district schools (they were not), that our selection policy be rewritten (it was), and that the Library Media Specialists be disciplined (we received a letter). The story gained national attention in the late summer and fall of 2013.

One of the most striking aspects of Emily Wheelock Reed’s story was the sense of isolation she felt. She received no support, particularly from the American Library Association who had published the list of recommendations which she used to purchase new books for Alabama state libraries. These feelings of isolation were familiar to me. Though my colleagues turned to each other for support, we received no support from the district school board or the district administration. This was the most difficult time in my thirty-six career as a high school educator. Though I had won the district’s Teacher Outstanding Performance award, was a finalist for Minnesota Teacher of the Year, and won the Lars Steltzner Intellectual Freedom award, choosing Eleanor & Park as the selection for a voluntary summer reading program felt like a threat to my career and to my job. As Toby Graham, University of Georgia’s University Librarian, asks in a video for the Freedom to Read Organization, “Who are the Emily Reeds of today, and who will stand up with them in their pursuit to insure our right to read?” Thankfully, the media, the Southern Poverty Law Center, our local teachers’ union, and others were supportive in many ways. In addition, the American Library Association, the Freedom to Read Organization, and other organizations now offer tools dedicated to Library Media Specialists who find themselves in similar situations.

One of the most striking aspects of Emily Wheelock Reed’s story was the sense of isolation she felt. She received no support, particularly from the American Library Association who had published the list of recommendations which she used to purchase new books for Alabama state libraries. These feelings of isolation were familiar to me. Though my colleagues turned to each other for support, we received no support from the district school board or the district administration. This was the most difficult time in my thirty-six career as a high school educator. Though I had won the district’s Teacher Outstanding Performance award, was a finalist for Minnesota Teacher of the Year, and won the Lars Steltzner Intellectual Freedom award, choosing Eleanor & Park as the selection for a voluntary summer reading program felt like a threat to my career and to my job. As Toby Graham, University of Georgia’s University Librarian, asks in a video for the Freedom to Read Organization, “Who are the Emily Reeds of today, and who will stand up with them in their pursuit to insure our right to read?” Thankfully, the media, the Southern Poverty Law Center, our local teachers’ union, and others were supportive in many ways. In addition, the American Library Association, the Freedom to Read Organization, and other organizations now offer tools dedicated to Library Media Specialists who find themselves in similar situations.

Eleanor & Park went on to be named a Michael J. Printz Honor book — the gold standard for young adult literature. It is the moving story of two outcast teens who meet on the school bus. Eleanor is red-headed, poor, white, bullied, and the victim of abuse. Park is a biracial boy who survives by flying under the radar. The two eventually develop trust in each other as the world swirls around them. They themselves don’t use foul language. They use music as a way to hold the rest of the world at bay. They fall in love and consider having an intimate relationship but decide, very maturely, that they are not ready for sex. As a Library Media Specialist, there were “Eleanors” and “Parks” who walked into my media center each and every day. Their story needed to be on the shelf in my library, so that they could see themselves reflected in its pages, to know that the world saw them and valued them, even if their lives were messy. For those more fortunate than these Eleanors and Parks, the story was important as well. By looking into the lives of others via books, we develop empathy and understanding, even when the viewpoints reflected there are not our own.

As artists — teachers, writers, actors, musicians, painters, dancers, and sculptors — it is our job to tell and preserve stories, the stories of all individuals, even when they represent beliefs different from our own. Knowledge truly is power. When we censor stories, we take away power. One need only look at history, and the burning of books and the destruction of libraries by those in power, for examples of the dangers of censorship. As we celebrate Banned Books Week (September 25th – October 1st), it is important to reflect on the value of artistic freedom and on the value of our freedom to read.

Though Garth Williams did not intend for The Rabbits’ Wedding to be a story about race and, thus, become a symbol of the Civil Rights Movement, it did. Though Rainbow Rowell did not intend for Eleanor & Park to become a symbol of censorship, it did. Alabama Story took place in 1959 but could just have easily taken place in 2001 with a book called Harry Potter, or in 2006 with a book called And Tango Makes Three, or … in 2013 with a book called Eleanor & Park. Censorship still occurs in 2016.

As the audience stood that evening, my husband and I applauded the Peninsula Players’ artistic staff, cast, and crew for telling Emily Wheelock Reed’s story. It is a story that needs to be told over and over again — for every “Eleanor” and every “Park” among us.

Terri Evans your article rings true and I will share your article. Great job with your message!

That is very kind of you! Thank-you!

Fascinating and important story, Terri. Thank you for the article, and thank you for standing up for young readers.

Although I don’t support censorship and would read these books myself, I find it troubling that the parents’ concerns about bad language and sexual content in books for teens were brushed aside. These are legitimate concerns that publishers would do well to consider when preparing a book for the YA market. As a YA book reviewer, I know that more parents don’t complain only because of their lack of awareness and trust in the industry, not because they don’t care.

Sorry, typo above. I meant to say that “more parents don’t complain only because of their lack of awareness and because of their trust in the industry, not because they don’t care.”

I wrote a short article on The Rabbit’s Wedding’ in my blog. https://misterscribbles.blogspot.com/2020/04/the-rabbits-wedding.html?view=mosaic I would like to add your excellent report here as a link. Would that be alright with you? Whenever I put in a link or picture I try to contact the owner, not always possible. I find your experience with the Elanor & Park book adds immediacy to the Emily Wheelock Reed story. Excellent writing on your part,

Sincerely,

Paul K Davis