Our thanks to author Candace Fleming for sitting still long enough to answer in-depth questions about her conception for, research into, and writing decisions for Presenting Buffalo Bill: the Man Who Invented the Wild West, our Bookstorm™ this month. Fleming’s answers will inform educators, providing direct quotes from an oft-published biographer of beloved books that will be useful for teaching writing and research skills in the classroom.

When did you first suspect that you’d like to write about William Cody?

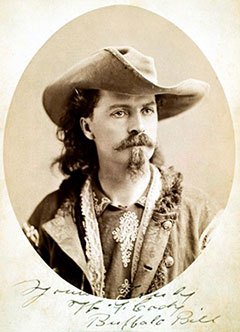

My first inkling occurred the morning I opened my email to find a message from editor Neal Porter. The subject-heading read: “Yo, Candy, want to do a book?” Neal had just returned from a trip to Cody, Wyoming, where he’d bumped into Buffalo Bill. Neal was not only intrigued by Bill, but he also realized that it had been decades since an in-depth biography of the showman had been written for young readers. But who should write it? He thought of me. Even though Neal and I had never worked together before, we’d been making eyes at each other for years. He hoped this project would finally bring us together. But I wasn’t so sure. Buffalo Bill Cody? In my mind, he was just another dusty frontiersman. A myth. A trope. Still, I decided to give him a shot (no pun intended) and ordered up his autobiography through inter-library loan. As I opened the book’s cover, I remember giving a little yawn. My expectations were low. And then … I fell into his life story. What a self-aggrandizing, exaggerating, exasperating, endearing, amusing, question-provoking storyteller! The man who wrote that book mystified me. Who was Buffalo Bill? Was he a hero or was he a charlatan? Was he an honest man or a liar? Was he a real frontiersman or was he a showman? I found myself suddenly brimming with questions. And I was eager to discover the answers. ©

At what point did you know that you’d present his life in terms of truth and maybe-not-so-true?

I knew right away that I would have to address the ambiguities in Will’s story. In fact, it was one of the reasons I was drawn to the project. I love the gray areas in history. I’m not just talking about gaps in the historical records. You know, those places where we don’t know for sure what happened. I’m talking about those places where we don’t know what to make of the historical truth. For example, Benjamin Franklin owned slaves. How do we fit that with with our image of the jovial, witty inventor and statesman? What are we to make of that? Or, take Amelia Earhart. Many of the most often-repeated stories about her aren’t true. Amelia made them up out of whole cloth. She lied. How does that jibe with our image of the daring, but doomed aviator? What are we to make of that?

Too often, especially in nonfiction for young readers, we avoid the gray areas. We don’t include these truths because we’re worried what kids will make of them. But I believe these areas are especially important for young readers … and most especially for middle school and teen readers. These are readers who are struggling to discover who they are and what they can be; they’re struggling to figure out their place in the world.

What’s right?

What’s fair?

What’s moral?

The last thing they need is another sanitized, pedestal-inhabiting, never-do-wrong person from history.

And so I decided to include both Will’s versions of events, as well as accounts that conflict with his. I intentionally incorporated opposing viewpoints from both historical figures and modern-day historians. And I purposely refrained from drawing any conclusions from the historical evidence. Instead, I chose to just lay it before my readers. Why? Because I want them to wrestle with the ambiguities. I want them to come to their own conclusions. I want them to see that stories — especially true stories from history — are not black and white. They’re gray.

And so I decided to include both Will’s versions of events, as well as accounts that conflict with his. I intentionally incorporated opposing viewpoints from both historical figures and modern-day historians. And I purposely refrained from drawing any conclusions from the historical evidence. Instead, I chose to just lay it before my readers. Why? Because I want them to wrestle with the ambiguities. I want them to come to their own conclusions. I want them to see that stories — especially true stories from history — are not black and white. They’re gray.

Who was right?

Who was wrong?

I don’t think it’s my job to tell them. I’m not sure I could tell them.

Rather, I choose to tell all sides of the Wild West story — Will’s side, the Native performers’ side — with what I hope was equal clarity and compassion. What choices do each make under pressure? Why? No one is all good. No one is all bad.

You see, it’s in the gray area between those opposing values that I hope readers will ask themselves: What would I do in this situation?

By including history’s ambiguities, I am “kicking it to the reader,” as my friend Tonya Bolden likes to say.

And this, I believe, is the purpose of nonfiction in the 21st century — to encourage thought, not simply to provide facts for reports.

When you begin your research, how do you lay out a strategy for that research?

I confess I never have much of a strategy plan when I begin researching. Instead, the process is pretty organic. I start with archival sources. What’s already been written and collected? I focus on primary sources: letters, diaries, memoirs, interviews. This is where defining, intimate details are found. As I read, I keep an open mind. I’m curious and nosy and I ask lots of questions. I actually write those questions down on yellow ledger pads. And let me tell you, I end up with lots of questions. I won’t find the answers to all of them. I may not even try to find the answers to all of them. But in this way, I remind myself that I’m exploring, making discoveries. In truth, I have no specific idea of what I’m looking for or what I’ll find. I let the research lead me. And, slowly, I begin to understand what it is I want to say with this particular piece of history.

In those initial stages, do you use the library? The internet? Other sources?

In the first throes of research, I’ll use the Internet to discover the collections and archives that hold my subject’s papers. I’ll search for autobiographies and other firsthand accounts of the person’s life. I’ll note the names of scholars or historians whose names pop up in association with my subject. That’s the very first step.

Did you visit the McCracken Research Library or the Buffalo Bill Center of the West?

The McCracken Research Library is part of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. In fact, the library is just down the stairs from their museum. Yes, I visited both. And I spent a week in the library, culling through years of scrapbooks kept by Will, and Annie Oakley and others, reading memoirs and letters and diaries.

Would you recommend that your readers visit those locations?

I would definitely recommend the museum to my readers. So much of the detritus of Will’s life is on display: his buffalo skin coat, his favorite rifle that he named Lucretia Borgia, the famous stagecoach from the Wild West. They even have his childhood home moved in its entirety from Iowa to Cody! The place really brings Will and his times alive.

What do you find to be most helpful about visiting a museum where artifacts are on display?

Those artifacts—leftovers of a person’s life, if you will—are so human. Sometimes we forget that a person from history was real flesh and blood. But then we’ll see that person’s well-worn carpet slippers, or read a love letter he wrote to his wife, and we’re reminded of that person’s humanity. Despite his place in history, he still suffered from both love and sore feet, just like all of us do.

How do you go about finding an expert to consult with about your book?

During research, certain names starting appearing again and again. I will not only note these names, I’ll do a quick Google to check on qualifications, as well as how up-to-date their scholarship is. For example, a name that’s cited again and again in Cody research is Don Russell. But Russell wrote his seminal work almost forty years ago. Certainly, his work is valuable, but it’s no longer the most recent scholarship. Young readers deserve the latest discoveries and newest interpretations. History is, after all, an ongoing process, one in which new facts are discovered, and old facts are reconsidered. So I turned to Dr. Louis S. Warren, a highly respected scholar of the Western US history at the University of California, Davis, as well as author of the critically acclaimed Buffalo Bill’s America. He very generously offered to read the manuscript, making several suggestions for changes, as well as pointing me in the direction of the latest Cody scholarship. He also suggested I contact Dr. Jeffery Means, an associate professor of Native American History at the University of Wyoming and an enrolled Member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe for his unique perspective on my book, particularly in regards to Great Plains Indian culture.

Do you research the photos you’ll include in the book at the same time as you research the historical and biographical elements? Or is that a separate process at a separate time?

I do my own photo research. While researching, I keep an eye open for things that might make for interesting visuals. I keep a list, and in most cases, a copy of those images. But I never know what I’m going to use until I start writing. The text really does determine what photographs end up in the book. Because of this, I always end up searching for photos late in the project.

How did you write the dramatic scenes from the Wild West Show? They’re filled with tension, vivid descriptions, and a movie-like quality. Were these actual scenes in the Show? And were you present to see them performed? It sure seems like it.

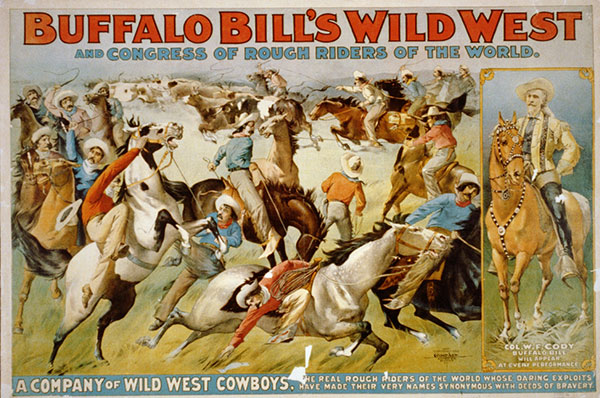

It was important to open each chapter of the book with a scene from the Wild West. Not only was I trying to show the parallels between Will’s personal experiences and the acts that eventually sprang from them, but also I wanted readers to have a clear understanding of what the show entailed. The best way to do this, I decided, was to write those scenes in a way that would make readers feel as if they were actually sitting in the stands. I wanted them to feel the tension, the excitement, the drama of the performance. I wanted them to experience (at least in a small way) the awe that show goers felt when they watched those re-enactments of buffalo hunts and Pony Express riders. After all, this is vital to the book’s theme—that the Wild West created our collective memory of the American West; that we still tend to think in tropes, and those tropes come directly from Buffalo Bill Cody. So, I wrote those scenes in great detail, almost in slow motion. Not a single description is made up. Everything comes from the historical record, including thoughts and comments from the people in the bleachers. I merely used present tense to make the action feel more immediate. But the action really and truly happened just as I’ve presented it.

It was important to open each chapter of the book with a scene from the Wild West. Not only was I trying to show the parallels between Will’s personal experiences and the acts that eventually sprang from them, but also I wanted readers to have a clear understanding of what the show entailed. The best way to do this, I decided, was to write those scenes in a way that would make readers feel as if they were actually sitting in the stands. I wanted them to feel the tension, the excitement, the drama of the performance. I wanted them to experience (at least in a small way) the awe that show goers felt when they watched those re-enactments of buffalo hunts and Pony Express riders. After all, this is vital to the book’s theme—that the Wild West created our collective memory of the American West; that we still tend to think in tropes, and those tropes come directly from Buffalo Bill Cody. So, I wrote those scenes in great detail, almost in slow motion. Not a single description is made up. Everything comes from the historical record, including thoughts and comments from the people in the bleachers. I merely used present tense to make the action feel more immediate. But the action really and truly happened just as I’ve presented it.

What a fascinating interview! I am very anxious to read this book, and I appreciate Candace’s in-depth research that helps readers see how “gray” history can be.