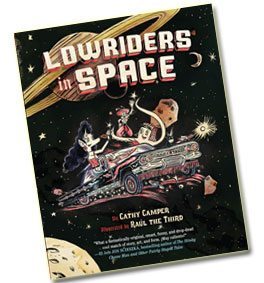

Lowriders in Space

Lowriders in Space

written by Cathy Camper

illustrated by Raul the Third

Chronicle Books, 2014

When did you first become aware of (or involved in) lowrider culture?

Probably in the early 1980’s, when I visited a friend of mine who lived in the Mission District of San Francisco. There were a lot of lowriders in the neighborhood, and since we were young women at the time, we’d get flirtatious attention from guys showing off their cars when we walked down the street.

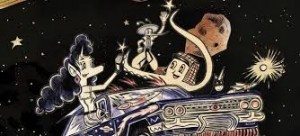

How was the decision made to make your three heroes non-human (the fourth hero, Genie, is a cat and I don’t need to ask why a cat is a cat)? They are an impala, an octopus, and a human … how did that come about?

Back when the book was just a daydream, I thought up the names of the characters first. I liked the name Elirio, and the name Elirio Malaria was really fun to say. I’d walk around thinking, Elirio Malaria, what kind of guy is he? Then one day it was as if a little voice whispered in my ear, “I’m not a guy, I’m a mosquito!” Duh!

Lupe (short for Guadalupe) Impala also got her name because it was fun to say, and because Impalas are the chosen cars of lowriders. She really is an impala, which is like a deer, or gazelle. For some reason readers don’t seem to know what kind of animal she is; they think she’s a fox, a wolf, a mouse?!? Raul and I thought it would be clear from her name, but you just never know…

And Flappy…I was reading an article about octopuses, and discovered there really is a super cute kind of octopus called a Flapjack Octopus, because its tentacles are short and stubby. Bam, you couldn’t ask for a better character.

It cracks me up when I hear the heroes described as a mosquito, an impala and an octopus, because I never thought of them as those animals first. Their animal nature came out of their names and personalities.

For the kids who’d like to make their own comics, how did you find Raul the Third? And when you found him, did the two of you work on developing the graphic novel together? Or was there the typical separation of author and artist?

Raul and I met via a mutual friend, who was drawing another comic I’d written. He couldn’t complete it, so he emailed me to suggest his friend Raul might like to work on it. I never finished that comic, but several years later when I’d written the script for Lowriders, I emailed Raul to see if was interested in a kid’s book, because I liked his art and knew we both had a good work ethic – we like to meet our deadlines.

He read it and wrote back, “This is the book I wanted to read as a kid,” and started sending me sketches the next day. He lives in Boston and I live in Portland, and we eventually met in person before embarking on such a big project, but from the start, it was obvious we had similar goals and shared the same sense of humor and approach to getting things done. In general, I write the story and he does the art, but we’re lucky that our publishers have let us collaborate a lot. Sometimes Raul will suggest plot changes or add dialog that fits with his choreography of the story. Likewise, sometimes I’ll specify some things that need to be shown in the art. It’s kind of like jazz, riffing off each other, where jokes and plot lines move back and forth between words and pictures. We also both have to adjust what we do to fit our editors’ and art director’s instructions.

Because a comic book or graphic novel often lets a story be told between the panels, did you do more editing to fit the illustrations than you might have with a picture book?

When I write the script, it’s very descriptive, because I’m trying to convey a whole world to Raul, my editors, and our art director. When Raul draws the thumbnail sketches, a lot of the writing falls out, because the story has now moved into the pictures. So if a character says, “Look, there’s a falling star!” once he’s drawn it, the character might just need to say, “Look!” I also try to leave some large spaces where big drama occurs, so the art can take over.

I think our book is different in this way from books like Drama or El Deafo, in that their art follows the plot line a little more directly, whereas Raul and I wanted sometimes to let the art just envelope the reader.

I don’t think it’s that different from writing a picture book, except I have to use waaay more exclamation marks. There are some parts of the writing I fight for, though, in order to maintain a rhythm, a poetry and to retain deeper layers of meaning.

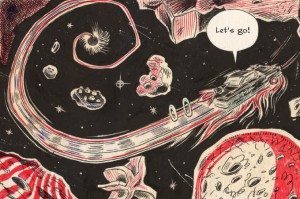

Did you set out to write a comic that had science elements in it? Was lowriding into outer space always a part of the concept?

I love science; it’s where I get tons of my inspiration because nothing is more unbelievable than what is true. My first idea for this book was that it would be cool to have a car that was detailed by outer space. So it was natural to include not just space science but the technology of cars. I also thought it was weird that we rarely see kids’ books about cars, when you think of the big part they play in our lives, and all the jobs folks have involving automobiles.

I love that this comic is virtually readable by any person of any age: was that a conscious decision?

My original target audiences were kids in third through fifth grade, English- Spanish readers, and boys, since their literacy rate is dropping. I also wanted something that wouldn’t seem babyish to older kids reading below grade level, since I work with a lot of kids like that as a librarian. And then Raul and I are both avid comics readers, so we wanted to include stuff that both parents and adult comics ‘ fans would enjoy. Plus a lot of it was just Raul and I making ourselves laugh.

My original target audiences were kids in third through fifth grade, English- Spanish readers, and boys, since their literacy rate is dropping. I also wanted something that wouldn’t seem babyish to older kids reading below grade level, since I work with a lot of kids like that as a librarian. And then Raul and I are both avid comics readers, so we wanted to include stuff that both parents and adult comics ‘ fans would enjoy. Plus a lot of it was just Raul and I making ourselves laugh.

Integrating Spanish into the story feels very natural—and I know a lot of people will be grateful for the instant translation on each page—which feels like a natural part of the comic book style. Was this a subject of discussion with your editor or art director?

Both Raul and I love Love and Rockets comics by the Hernandez brothers, (an adult comic). They always used drop-down translations and explanations beneath their comic’s frames for things readers might not understand. Our comic is definitely an homage to theirs (they have a female mechanic named Maggie who works on rockets, and who is Lupe’s role model) and so we thought it was natural to do this in our book as well. I wanted to include a glossary for many reasons, but first and foremost, to empower any kid to read. Incarcerated kids, immigrant kids, kids whose parents don’t speak English or Spanish, or don’t read super well. I wanted to give kids the opportunity to figure it out themselves. Also, learning to use a glossary is a skill in and of itself, which ties in with curriculum goals, which schools need to meet. And then there’s the kids that tell me, “I just love reading glossaries! “

Have you done any work on your own car?

Naw, although my car is kinda low and slow. It’s old and faithful.

Do you have plans to go into outer space?

No, I like looking at meteor showers, and the night sky, and spying on outer space through telescopes. I guess I’m not focused on just one field of science. I love talking to scientists and learning what’s new and cool. There’s so much to discover, and we live in an age where a lot is going on.

Does the group El Lupe y su Quinteto Impala have anything to do with Lupe’s name?

Ha! Nope, that’s a total coincidence. Although I do love cumbia!

For classroom teachers who might be working with students who are writing a comic book, what advice would you give them about the writing side of this?

As a writer working with an artist, you have to agree to collaborate. So you want to figure out right at the start who does what. Some artists want the writer to do all the writing, break down the dialog frame by frame, and even describe what they should draw in each frame. Other artists prefer more freedom. And the same can be true of writers. Some demand to have a lot of artistic control about how the art will look. Others are more open. If it’s clear from the beginning, no one’s feelings will get hurt.

Do a rough form of the comic, penciling everything in loosely, before you commit to something that will take a lot more work. That way, you can work out your mistakes before you invest too much time in it. One very important thing is to figure out where each page will fall. If you look at a comic, you’ll see how important it is, where each panel lands. A big double page splash page has to land on two pages that lay next to each other. So it really helps to make a rough mock-up of your comic to figure this out.

I notice on the title page it says “Book 1.” Dare we hope for a Book 2?

Oh yes, book two is in the works as I write this, and it’s bigger and just as over-the-top as book one. Our intrepid heroes take a road trip in the opposite direction, into the center of the Earth! It will be out in spring of 2016.