When Debra Frasier’s first book was published thirty years ago, we were invited to celebrate the unique experience of each child born into this world. On the Day You Were Born has been a gift for babies, children, and families ever since. It’s often read out loud annually during birthday celebrations. Minnesota’s Shoreview Public Library features the book in a wall-sized art installation warming the hearts of patrons, who are reminded of the joy in this book.

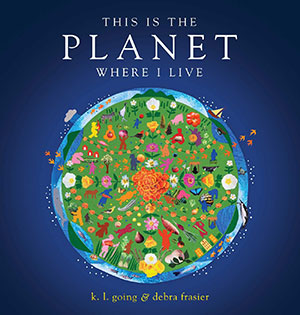

This year, Debra honors our world, including the creatures who live here, the places we live, clouds in the sky, the fields where we grow foods that sustain us. Illustrating a book written by K.L. Going, This is the Planet Where I Live, Debra Frasier works with collage that exuberantly celebrates our connections to everything on this earth.

When you receive a manuscript, do you know immediately how you will express the book with your art? Does a picture spring to mind?

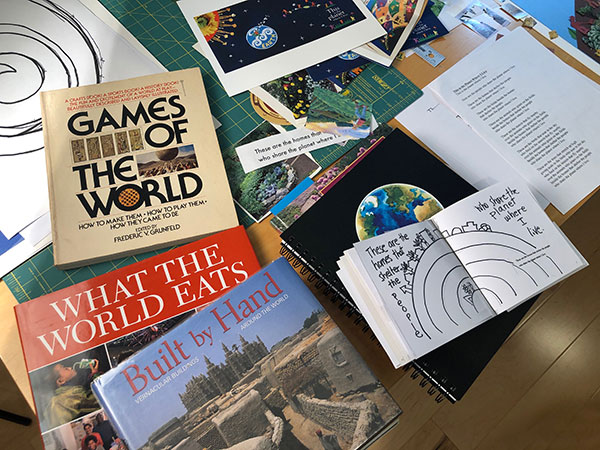

Oh, good heavens no! That’s the point: NOT KNOWING! That’s the fun. That’s the journey, the learning adventure! After agreeing to illustrate a story that someone else wrote, I immediately get a blank journal — large, spiral. I make a front piece page and begin the search for glimmerings in the dark. I look for visual cues, places that are drawing my attention in response to my query of the universe: What does this book look like? No judgments. I’m just on the lookout for something that flashes a tiny spark … maybe a magazine picture, an Instagram post, an overheard comment at the bakery. It all goes in the Journal. This is how I learn what the book will look like. I will always be using scissors, paper, and glue, but how? Will I make the paper? Paint it? Collect it? Purchase it? I’ve been criticized for my “style” being all over the map, lacking consistency, but honestly, that would bore me to tears. It’s the search, the frustration, the tries, and the unexpected combinations that I love.

You didn’t write this book, so what considerations are different than they would be for a book you’ve written?

It is traditional for the author and the illustrator not to meet, so the illustrator remains free to envision the book without constraints, to see the story freshly through their own eyes. But when I am writing and illustrating, we talk to each other all the time — and the Journal has been filling since inception with the parallel channels of words and images. I prefer that. But every once in a while a manuscript comes along that startles me enough to turn my head and stare, deeply. Kelly Going’s manuscript was like this.

It is traditional for the author and the illustrator not to meet, so the illustrator remains free to envision the book without constraints, to see the story freshly through their own eyes. But when I am writing and illustrating, we talk to each other all the time — and the Journal has been filling since inception with the parallel channels of words and images. I prefer that. But every once in a while a manuscript comes along that startles me enough to turn my head and stare, deeply. Kelly Going’s manuscript was like this.

Can you share with us your initial decision-making process for this book? Out of all the materials available, how do you decide on what you will use?

I know that I will be collaging with paper for each project I do. But the variables inside that choice are infinite. For example, on This Is The Planet Where I Live, I spent about a year experimenting with creating “paste papers” to use in the collages for this book. (Paste paper is a Japanese technique for coloring paper that uses a goopy paste of rice flour and colored with pigments, sort of like finger painting for adults.) In 1992 I had illustrated William Stafford’s poem, The Animal That Drank Up Sound, in this way. But the papers turned out to be too heavy, too thick, for the lightness this book needed. I stumbled on an Instagram post of some textiles from Uzbekistan that threw off so many sparks for me that I ended up printing about twenty of these posts and putting the images in my Journal to study. It was so lucky because the posting site moved on to ikat textiles from Afghanistan next and has never gone back to those lively images from Uzbekistan! Lots of things influence a design decision but this was a big one, right up there with my Tai Chi teacher’s random comment: “Do not forget that this is the planet of all things that sprout.” That was not just a spark — that comment was a fire for me!

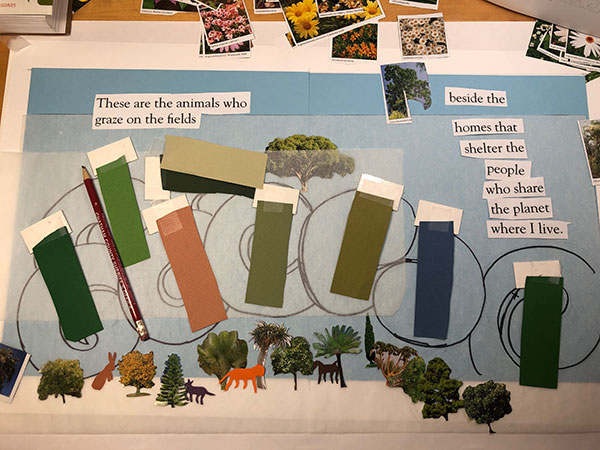

Once you decided on collage, how did you go about organizing images so you could assemble them into artwork?

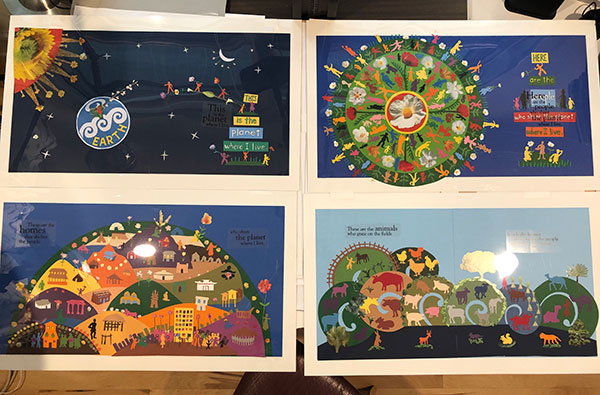

I ended up using French Cansons papers — strong, flatly colored, slightly textured on one side, and easily purchased at my local craft store. I keep the large Cansons sheets on my studio walls, pressed to a metal strip with a strong magnet for each sheet. This lets me easily snip off bits to try. I also made a “poster” of each available Cansons color, each sampled in a strip, and attached with removable tape. This poster is a very important tool for trying out color choices. Planet came to require the accumulation of hundreds and hundreds of tiny pictures of “the things that sprout” and I managed those in small plastic boxes, labeled and stored as you would 4×6 inch photos. This proved to be a fabulous system. If I needed yellow flowers, I’d pull out the YELLOW box.

How do you edit what you’re doing?

Well, you have hit on the golden secret of collage — if you wait to glue until the end of building an image, it is constantly being edited as you create it. Many times I just sweep everything off and start over. This is why I love this method! I would not call myself a great illustrator but I CAN edit until I get something near my idea of RIGHT!

Did you work with a computer?

I do not work with a screen in the building of the original images. Each picture exists in full size, made from scissors, paper, and glue. At the end, when the book’s pictures are finished, my husband, the photographer James Henkel, takes them into our maintenance room where we have a copy stand with lights set up. (It is very dark in there!) Together we shoot a photo of each illustration. This transforms my paper-collaged pictures into digital images and they can now be opened in Photoshop. Color accuracy to the originals is degraded in this step, but Jim and I work together to try to get a match back to the originals. (This was a very difficult step in this Planet’s creation, and we are not sure why as we’ve used this process in every book. Mystery.) The corrected digital images are sent to the publisher’s designer, who then lays in the type for each page. This is a HUGELY important role in the book’s final look. I was particularly lucky to have Michael McCartney, at Beach Lane Books (S&S), working with me on this step. He was not only brilliant — he was also incredibly patient! Just look at this book’s cover: beautiful! Michael did that.

Is there a point at which you begin to consider the reader, the person absorbing the text and illustrations?

The readers and the listeners are with me from the very start. I have had the privilege of making picture books for three decades plus. Now parents who heard On the Day You Were Born as a child read it to their own kids. My role is to bring the shoulders together of family, or a classroom, all leaning in, all waiting to be transported through the lifting of a cover. I find and make the story but it is nothing without this leaning in to listen, nothing but a pile of paper. So I always have this image of where we are headed with me as I think about the making of a book. I don’t let their judgments enter in, but I let their eventual delight carry me through. I am very, very slow at making books. For me, it takes years and years for each one. Without the image of the readers with me, with the goal of that leaning in and lifting the cover together, I would never make it.

You are a thoughtful and sharing photographer and videographer. How are these part of an illustrator’s toolbox? Why do you take photos of the book in the making?

Because every book is a mystery for me as to how it will turn out — and because I build the Journal I mentioned to help me make sense of the clues along the way — I am as surprised as anyone else as to see how it came out! (I want your readers to know that I ALWAYS doubt if I can pull it off when I start.) When the book is done I love to tell the story of the process of this unfolding mystery, hoping it will reveal some clue that will be helpful to someone else’s process. I have been so helped by my years at Penland School of Craft where I met hundreds of fiercely independent makers who taught me, through their process presentations, that there are a zillion ways to do anything — and I could learn my own way. It’s part of my pay-it-forward work with kids, especially. Every project starts tiny. This is such an important concept to grasp early on. Life changing. Taking pictures along the way helps make the story of the adventure real.

How is submitting illustrations for a book different now than it was when you created On the Day You Were Born thirty years ago?

I have worked with the same editor, Allyn Johnston, for all of my years in publishing. This makes a difference in that she understands my hands-on, no-screen way of working, and supports it. (My dummies — practice books — are made of real paper, with real paper images!) So I’ve been able to keep my image making process the same in those 30+ years. I just love scissors, paper, and glue. (Know that I have learned to use Procreate — a drawing program — on my iPad, and love playing with that, so I am not a complete Luddite. But for books, I want to keep it real. Scissors. Paper. Glue.)

The next part I am going to answer with some detail for the historical record! It may be too boring for anyone else:

In 1990, when I finished the art for On the Day You Were Born (1991) we shot the original collages (scaled much larger than the trim size of the book) on the same copy stand I use today, but the end result differed. In 1990 we shot on film, and from that 4×5 film, gorgeous, accurate color “transparencies” on film were our goal. Those transparencies were then scanned and made into digital files.

The original art was actually sent to Singapore and “on-press color checking” was a part of the printing process. Under special lights, adjustments were made as the presses thundered to match the original art to the sheets coming off press. Out of the Ocean, my 1998 book, was printed in Mexico and I was able to see this book on-press, and watch the very talented press checkers use the challenging original art to adjust the press’ ink flow. That was an amazing experience. Miss Alaineus, A Vocabulary Disaster, (2000) was my last book to use transparencies (and we used an 8×10 film camera for photographing that art — gorgeous artifacts!). Now we go direct to digital when we photograph the collage art. The original art no longer accompanies the presses as digital files can be proofed from a few test pages and adjustments made there as color match accuracy is now greatly improved.

One question might be: why not just scan the original art?

- When scanned, cut paper collage edges cause shadows that I find unacceptable in the printed image.

- I work very large and a scanner to accommodate this scale is both hard to find and very expensive!

What are your hopes for this book?

I think the author Kelly Going said it well when asked where she found the inspiration for this book:

“Joseph Campbell wrote, ‘we need myths that will identify the individual not with his local group but with the planet.’ This is the quote that inspired the text for This is the Planet Where I Live. If you replace the word “myths” with “stories,” you can easily see how this quote inspired the book … the more we begin to see all people as our people, the closer we’ll come to achieving peace.”

When I read this manuscript I immediately sensed what Kelly did — that here was a chance to make the pictures for a story I desperately needed to hear right now — a book that delivered a vision of a world where all of us are connected. I hope this book can help teachers and families lean in and see that too. Here it is, in glowing color, a story for our time, a story that weaves us all together.

Resources

Debra’s Paper Camp (grab some paper, scissors, glue, and a cup of tea)

Sign up for Debra’s Scissors Paper Glue, her once-monthly, four-items each time newsletter with a delightful video how-to.

Thank you for your wonderful descriptions of the way you work, Debra. Your photos were so interesting. I am looking forward to reading and seeing This Is the Planet Where You Live.

It’s such a beautiful book; I look forward to when I can leisurely pore over each illustration. It’s inspiring, and mind-opening to hear how other artists work. Seeing your studio was also inspiring; it made me want to start creating something now. Thank you, Debra!