Kurtis Scaletta is an experienced writer of middle grade and chapter books. His Topps League series of baseball stories and his novels Mudville and The Winter of the Robots are particular favorites of this interviewer. Now his first picture book is out and we’re curious about his experience of writing in this format.

This is your first picture book. What were your guidelines for revising your initial text into its spare but enticing picture book form?

Kurtis: This is the first picture book I’ve published, but I’ve written too many to count. I think the same is true of almost anyone who’s published a picture book.

My advice on revision is to write the first draft without worrying about length. Then go in and tighten it up. It might take several read throughs to get it where it needs to be. At the same time you need to make sure there’s a full narrative there, and that there are at least 12 distinct scenes.

I usually use a table late in the process. I put text in one column and describe what visuals there might be in another column. Ideally there will be exactly 12 rows – even though the picture book is 32 pages, with the title page and end papers and so forth you end up with 12 spreads (or 24 pages). That also helps with pacing. If you notice lots of text in one cell (on one page) you probably want to revise.

It’s a dinosaur book, of which there are quite a few. And yet, dinosaurs are equal opportunity subjects of fascination for so many kids. Were you conscious of those other dinosaur picture books? Did your concept for the story change over time?

Kurtis: I think of it as a bird book! But of course I’m happy to tap that universal interest in dinosaurs. I didn’t seek out other books about birds or dinosaurs. My own son had a few dinosaur books but was more into dragons. A lot of books about dinosaurs treat them in the same mythical way, they don’t show how we got here from there.

The story didn’t change that much from draft to final edition. There was all that tightening I talked about, but the premise and basic plot were the same.

I visualized a crucial spread in the book from the beginning, and it’s still there. The book always hinged on that moment in the story. In fact I think we also discussed how to do that scene more than anything else in the book. Nik Henderson made some creative decisions about how to execute it, too. I think he nailed it, by the way.

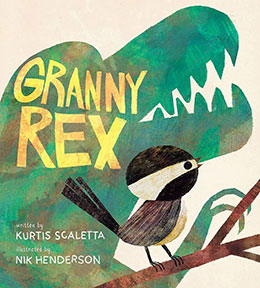

published by Cameron Kids, 2023

This is a terrific book for opening discussions about evolution and climate change and yet, those words are not a part of the text. How did you manage to include those concepts?

Kurtis: I’ve been interested in evolutionary biology for a long time. One book that sparked this interest is Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari. It really explores the link between biology and human nature. I’ve been recommending it to everyone; I think it’s the book of the century for me. I came to birds by trying to write about humans.

I’ve also thought about previous climate disasters. There are a few in human history, like in 1815 when two volcanos caused “The Year Without a Summer.” The end of the Ice Age was slower but more transformative. The few thousand humans scattered around the globe at the time must have felt like it was the end of the world. That meteor that landed in what is now Mexico is probably the biggest environmental disaster in the history of the earth.

Maybe I wanted to look toward our own climate crisis a little more hopefully, believing that life will adapt.

There’s an attitude and confidence in knowing where you come from. Knowing family history can be crucial, especially when it inspires little Dee to stand up for what’s right. Was this one of your original story intentions?

Kurtis: I had that idea of writing a story that takes a long view, evolution as family history, before I knew it was about a bird and a dinosaur. We also have ancestors from a million years ago or even a hundred million years ago, and we literally have them in our “feathers and bones,” as Dee’s mother would say. The stroke of inspiration was making it about a bird instead of a person; it simplified things. And there’s a starker difference between a giant therapod stomping around and a little bird twittering away on a tree branch. That contrast really made it striking and fun.

The endpapers are so right for this book, evoking dinosaurs with close-up textures. On the pages of the story, illustrator Nik Henderson focuses on comparisons of size. Confidence beams from the pages. What are your favorite aspects of his illustrations?

Kurtis: I love the end papers too, I wanted a scene like that that captures the transformation of dinosaurs to birds. My favorite illustration is the one I mentioned earlier, that crucial scene where Dee evokes her inner dinosaur. That scene was in my head from the beginning. I’m really happy with the way it turned out; I’m going to have a print made and hang it up!

I couldn’t put it better than you just did about the style — confidence beaming up from the page. Dee’s confidence is there and so is Nik’s. I’ve seen other of his work that’s a lot more detailed, but this book did need those few broad strokes and bright colors.

Thanks for taking time out from launching your first picture book, Kurtis, to grant Bookology an interview. We hope you and Nik get all the roaring-good feedback this book deserves. Readers, be sure to check out the endpapers before and after reading this book out loud!