For young writers who aspire to write information books of their own, we’d like to help them understand how a writer works.

When do you remember becoming aware of Dr. Jane Goodall?

When do you remember becoming aware of Dr. Jane Goodall?

I worked at Houghton Mifflin when many of her books were being published and knew her editor well. The first time I heard her give one of her brilliant lectures, I became a total convert.

What flipped the switch for you to consider writing a biography of her?

My editor, Kate Olesin of National Geographic, asked if the project would interest me. They had access to photos and could put me in touch for interviews with people who had worked closely with her. Since her 80th birthday was approaching, I loved the idea of a biography that covered her entire life.

Why was it important for you to write about Dr. Goodall’s life for young readers?

Her passion, her dedication to her cause, and her ability to take a childhood interest, a love of animals, and turn it into her life’s work. I think children need heroines and heroes – and Jane Goodall qualifies as one.

How many books do you estimate you read to write about Dr. Goodall’s life?

Probably around 70 or so, and then I watched documentaries, video clips, and read interviews. You do so much more research for a nonfiction book than ever shows. But in the end, everything you examine enters into what you write.

Where did you look to find info about her childhood, which you use so effectively to establish what motivated her choice of her life’s work?

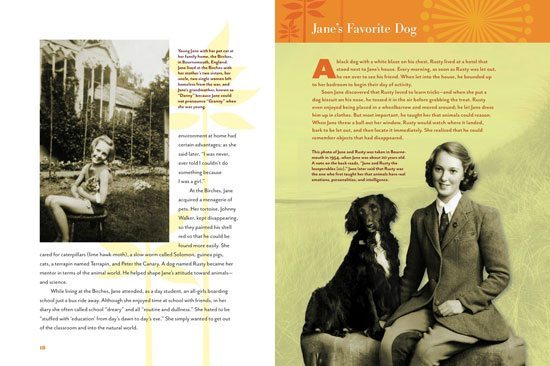

Fortunately a great deal has been written about her childhood, both in secondary sources and by Jane herself. But to write that chapter I was often taking a scene or idea from one book and combining it with ideas and scenes from another. Writing narrative nonfiction is often like stitching a quilt together, and scraps come from a variety of sources.

At what point did your ideas for writing this book come together with a single, prominent thread that gave you a focus for Untamed?

By the time I had finalized the outline, I knew the direction the story would take. Solid nonfiction writing depends on a good scaffold. If you don’t get that right, you have to redo and redo until the structure is sound.

When did you start writing Untamed and how long did it take you before you sent the final copy edits back to your publisher?

We had a schedule from the beginning of the project. I had a year for the first draft; we finished editorial revision in 6 months. I have never worked with an editor as efficient and effective as Kate. She knows how to keep a project on track!

There are Field Notes at the end of the book that include facts about chimpanzees, biographies of the Gombe chimpanzees, and a timeline of Dr. Goodall’s life, among other things. Did these come out of your research? Did you begin by knowing what you wanted for back matter or did that emerge after you gathered your information?

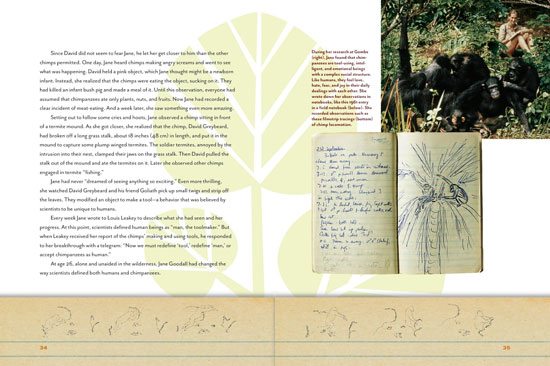

Some of these I knew I needed, like a timeline. But the editorial staff at Nat Geo, who work on nonfiction all the time, had a lot of creative ideas – such as fun facts about chimps or the family photo album. Also because of their expertise, the back matter has been designed to be attractive and readable for children.

What was your favorite part of creating this book?

Seeing the bound volume. I knew Untamed was going to be beautiful – but the final book took my breath away.

What makes you the most proud about Untamed?

Jane Goodall herself and the Jane Goodall Institute read both the manuscript and the final pages, checking for accuracy and interpretation. I am very proud that Jane Goodall considered the book worthy of this attention – and thought well enough of the book to write an introduction.