In this interview with Marion Dane Bauer, we’re asking about her novel-in-verse, Little Cat’s Luck, our Bookstorm™ this month, written for second, third, and fourth graders as a read-aloud or individual reading books. It’s a good companion to her earlier novel-in-verse, Little Dog, Lost.

In this interview with Marion Dane Bauer, we’re asking about her novel-in-verse, Little Cat’s Luck, our Bookstorm™ this month, written for second, third, and fourth graders as a read-aloud or individual reading books. It’s a good companion to her earlier novel-in-verse, Little Dog, Lost.

When the idea for this story came to you, was it a seed or a full-grown set of characters and a storyline?

I began by sitting down to write another Little Dog, Lost, but not with the same characters, so it was easiest to start with a cat. When I begin a story, any story, I always know three things: who my main character will be, what problem she will be struggling with (knowing the problem, of course, includes knowing about the story’s antagonist, in this case “the meanest dog in town), and what a resolution will feel like. So I knew Patches would be lost and I knew she would encounter “the meanest dog in town” and I knew she and Gus must be believable friends in the end. I wasn’t sure, though, how their friendship would evolve. So I sent her out the window after that golden leaf and then waited to see what would happen.

You've stated that Little Cat's Luck is a "companion book" for your earlier novel-in-verse, Little Dog, Lost. What does that term mean to you?

You've stated that Little Cat's Luck is a "companion book" for your earlier novel-in-verse, Little Dog, Lost. What does that term mean to you?

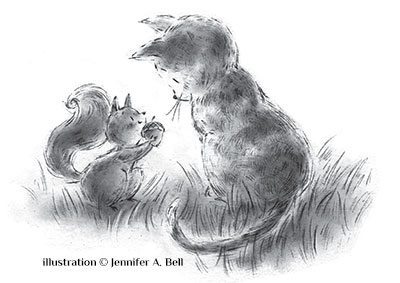

It’s not a sequel, because it’s not the same characters or the same place (though it’s another small town). I have however written it in the same manner—a story told in verse through a narrator—which gives it the same kind of feel. The same artist, Jennifer Bell, did the illustrations, too. Each book stands alone, but they could also be read side-by-side, compared and enjoyed together. One significant difference is that Little Cat’s Luck is entirely devoted to the world of the animals where Little Dog, Lost is focused more on the humans. In Little Cat’s Luck we see the humans only tangentially as they affect the animals, and because the animals stand at the center of the story I allow them to converse with one another. That doesn’t happen from the human perspective of Little Dog, Lost.

When you're writing animal characters, which you do so well, from where are you drawing knowledge of their behavior?

I have always had animals in my life, cats when I was a child, both dogs and cats as an adult, though in recent years I’ve grown somewhat allergic to cats so no longer have them in my home. But I have lived with dogs and cats, paid close attention to them, loved them all my life, and when I turn to them as characters in a story I know exactly how they will be. In fact, since I can’t cuddle real cats any longer without ending up with itchy eyes, I found deep pleasure in bringing Patches to life on the page.

In creating Patches, you've imbued her with characteristics and dialogue that could be identified as human and yet you've maintained her animal nature. At what part of your process did you find yourself watching for that border between human and animal?

The moment I give an animal human speech, I have violated its animal nature. We are who we are as humans precisely because we talk, and we do it constantly, with good and bad results. We converse to understand one another, and we call one another names. In stories it can be very difficult to hold onto the animal nature of a dog or cat while human words are coming from their mouths. When I wrote my novel Runt, about a wolf pup, I chose to give the animals speech, following the pattern of marvelous writers such as Felix Salten, the author of Bambi, a Life in the Woods. And while that was a very intentional choice, it was a choice I found myself not wanting to repeat when I considered writing a sequel to Runt. I returned to my wolf research in preparation for writing that second book and found myself so impressed with the subtle, complex ways wolves actually communicate with one another that I put the idea for a sequel aside. I found I didn’t want to put speech into their mouths again. However, when I wrote Little Cat’s Luck I put that concern aside easily, partly I suppose because cats are domesticated animals, so speech felt less a violation. I gave them roles that are familiar in our human world, too, for Patches be a mother and for Gus to be a hurting bully, which made it easy to know what they might say. Throughout, though, I retained their animal nature by staying close to their physicality. Describing the way they move and the things they do with their bodies kept their animal natures in view.

The moment I give an animal human speech, I have violated its animal nature. We are who we are as humans precisely because we talk, and we do it constantly, with good and bad results. We converse to understand one another, and we call one another names. In stories it can be very difficult to hold onto the animal nature of a dog or cat while human words are coming from their mouths. When I wrote my novel Runt, about a wolf pup, I chose to give the animals speech, following the pattern of marvelous writers such as Felix Salten, the author of Bambi, a Life in the Woods. And while that was a very intentional choice, it was a choice I found myself not wanting to repeat when I considered writing a sequel to Runt. I returned to my wolf research in preparation for writing that second book and found myself so impressed with the subtle, complex ways wolves actually communicate with one another that I put the idea for a sequel aside. I found I didn’t want to put speech into their mouths again. However, when I wrote Little Cat’s Luck I put that concern aside easily, partly I suppose because cats are domesticated animals, so speech felt less a violation. I gave them roles that are familiar in our human world, too, for Patches be a mother and for Gus to be a hurting bully, which made it easy to know what they might say. Throughout, though, I retained their animal nature by staying close to their physicality. Describing the way they move and the things they do with their bodies kept their animal natures in view.

Gus, the dog, is at once the "meanest dog in town" and the character who earns the most sympathy and admiration from readers. Was the "villain" of your story always this dog? Did he become more or less mean during your revision process?

Gus was always the villain, and he always started out mean. In fact, I didn’t know how mean he could be until he took possession of those kittens … and then of Patches herself! But by that time I understood Gus, understood the need his pain—and thus his meanness—came from, and thus knew he was acting out of desperation, not out of a desire to hurt. So that meant my story could find a reasonable and believable solution, that Patches, the all-loving, all-wise mother, could succeed in reforming “the meanest dog in town.”

How conscious are you of your readers, their age and reading ability, when you're writing a novel like Little Cat's Luck or Little Dog, Lost?

When I’m writing, I’m focused on my story and my characters, not my readers. I hope there will be readers one day, of course, but I’m writing through my characters, through my story without giving much thought for what will happen to it out in the world. If I can inhabit my story well, and if my story comes out of my young readers’ world, it will serve them. However, reading ability is another matter, and one I must take into consideration. I have written many books for developing readers, and I love the kinds of stories that work for young readers, so I have loved writing them. I wrote a series of books for Stepping Stones aimed at developing readers, ghost stories The Blue Ghost, The Red Ghost, etc., The Secret of the Painted House, The Very Little Princess, and more. And they were a great pleasure to write. But after I time I grew restless over having to write in short sentences to make the reading manageable for those still developing their skills. So when I came to write Little Dog, Lost, I said to myself, What if I wrote in verse? If I did that, the bite-sized lines would make it easier to read, and I wouldn’t have to alter the natural flow of my style. I did it, and it seemed to work, not just for reviewers and the adults who care about kids’ books, but for my young readers themselves. And I have been very happy with having discovered a new—for me—way of presenting a story. That’s why I decided to do Little Cat’s Luck in the same way.

When I’m writing, I’m focused on my story and my characters, not my readers. I hope there will be readers one day, of course, but I’m writing through my characters, through my story without giving much thought for what will happen to it out in the world. If I can inhabit my story well, and if my story comes out of my young readers’ world, it will serve them. However, reading ability is another matter, and one I must take into consideration. I have written many books for developing readers, and I love the kinds of stories that work for young readers, so I have loved writing them. I wrote a series of books for Stepping Stones aimed at developing readers, ghost stories The Blue Ghost, The Red Ghost, etc., The Secret of the Painted House, The Very Little Princess, and more. And they were a great pleasure to write. But after I time I grew restless over having to write in short sentences to make the reading manageable for those still developing their skills. So when I came to write Little Dog, Lost, I said to myself, What if I wrote in verse? If I did that, the bite-sized lines would make it easier to read, and I wouldn’t have to alter the natural flow of my style. I did it, and it seemed to work, not just for reviewers and the adults who care about kids’ books, but for my young readers themselves. And I have been very happy with having discovered a new—for me—way of presenting a story. That’s why I decided to do Little Cat’s Luck in the same way.

Little Dog, Lost was your first novel-in-verse. With Little Cat's Luck, are you feeling comfortable with the form or do you feel there are more challenges to conquer?

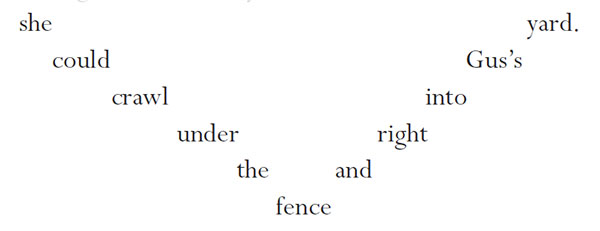

I was much more comfortable with the form with Little Cat’s Luck. When I started Little Dog, Lost I felt tentative. Could I really do this? Would anyone want it if I did? Was I just dividing prose into short lines or was I truly writing verse? So many questions. But after a time, I grew to love the form, and when I was ready to start again with a new story, I knew verse was the right choice. The one change I brought to verse form in Little Cat’s Luck is that this time I began experimenting with concrete verse, letting a word fall down the page when it described falling, curl when Patches curls into a nap and more. That was fun, too, but the challenge was to play with the shape of the words on the page without making deciphering more difficult for young readers. I’m guessing there will be more discoveries ahead if I return to this form.

Do you think visually or primarily in words?

Totally through words. Absolutely and totally. In fact, when I receive the first art for one of my picture books, I always go through the entire thing reading the text. And then I say to myself, “Oh, I’m supposed to be looking at the pictures!” and I go back to look. I didn’t have to prompt myself to be more visual, though, to play with the concrete poetry. Once I’d started doing it, opportunities to do more kept popping up, so even though I was using only words my thinking became more visual.

What is the most important idea you'd like to share with teachers and librarians about Patches and Buddy that you hope they'll take with them to their students and patrons?

I believe that the most important thing a story does, any story, is to make us feel. By inhabiting a story, living through it, we are transformed in some small—or sometimes large—way. I know that when stories are used in the classroom, they are used for multiple purposes, and that is as it should be, but I hope adults presenting Patches and Buddy will first let the children experience the boy, the dog, the cat, will let them feel their stories from the inside. After the stories have been experienced, as stories, there is plenty of time to use those words on the page for vocabulary lessons or as a prompt for children to write their own verse stories or anything else they might be useful for. But always, I hope, the story will be first.

I believe that the most important thing a story does, any story, is to make us feel. By inhabiting a story, living through it, we are transformed in some small—or sometimes large—way. I know that when stories are used in the classroom, they are used for multiple purposes, and that is as it should be, but I hope adults presenting Patches and Buddy will first let the children experience the boy, the dog, the cat, will let them feel their stories from the inside. After the stories have been experienced, as stories, there is plenty of time to use those words on the page for vocabulary lessons or as a prompt for children to write their own verse stories or anything else they might be useful for. But always, I hope, the story will be first.

____________________________________________

Thank you, Marion, for sharing your thoughts and writing journey with us.

For use with your students, Marion’s website includes a book trailer, a social-emotional learning guide, and a teaching guide that you’ll find useful as you incorporate this book into your planning.

I loved both Little Dog Lost as well as Runt! I agree – the books I love most are those that move me, I love what you said about transformation – we change as the protagonists change!

So looking forward to reading Little Cat’s Luck!