How many books can you name that are about surveying … and a mystery? I know. Right? And yet we see surveyors every day in fields, on busy street corners, and in our neighborhoods. What are they doing? Would it surprise you to know that nearly every acre of your state has been surveyed? That knowledge about those acres is recorded on plat books and maps that people in government and commerce consult all the time?

How many books can you name that are about surveying … and a mystery? I know. Right? And yet we see surveyors every day in fields, on busy street corners, and in our neighborhoods. What are they doing? Would it surprise you to know that nearly every acre of your state has been surveyed? That knowledge about those acres is recorded on plat books and maps that people in government and commerce consult all the time?

What if 40 acres of old-growth trees (actually 114 acres) were somehow recorded incorrectly by surveyors in 1882? What if those trees were left to grow, undisturbed, because they appeared on maps as a lake? Then you would have The Lost Forty, which inspired The Lost Forest, by Phyllis Root, illustrated by Betsy Bowen (University of Minnesota Press).

So interesting to learn how those surveyors worked, the instruments they used, the clothing they wore to fend off the snow, sun, and insects. Then the author invites us to think about the challenges of surveying:

If you have ever walked through the woods

you know the land doesn’t care

about straight lines.

This book’s format is tall, just like those old-growth pines, and it contains all kinds of information that will fit beautifully into your STEM curriculum.

The writing is engaging, telling a true story and inviting us to use all of our senses to explore the story. Betsy Bowen’s illustrations cause us to linger, examining each page carefully.

used here with the permission of the University of Minnesota Press

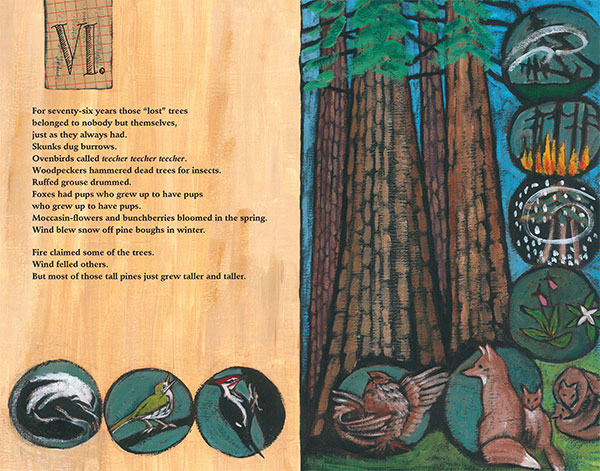

In the back matter, there’s a list of 15 trees, flowers, and birds that may live in old-growth forests. You and your family can travel to The Lost Forty Scientific and Natural Area in the Chippewa National Forest to conduct your own expedition, using the book to identify these species.

In addition, the book offers notes about how land is measured (fascinating … and something you could do as a field trip), How to Talk Like a Surveyor (“meander line”?), and How to Dress Like a Surveyor (practical). Do not miss Betsy Bowen’s illustrations of Phyllis and Betsy on the last page!

Two admirable picture book creators, Phyllis Root and Betsy Bowen, have teamed up once again to bring us a fascinating and beautiful book about those incorrectly surveyed acres of trees. Bookology asked them how this book, sharing an unusual history, came to be.

Phyllis Root, author:

Phyllis Root, author:

I was working on a counting book, One North Star, for the University of Minnesota Press about habitats in our state and the plants and animals that live in those habitats. That led me to Minnesota’s Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), and on a trip north to visit the Big Bog I made a detour to see the Lost Forty SNA and was enchanted. The trees, some four hundred years old, tower so tall that it’s hard to see the tops, and the trunks of some are so big it takes three people to wrap their arms around. Since then I’ve gone back at least once each year, not only to see these amazing trees but also to look for the wildflowers that grow around them — bunchberry, moccasin flowers, rose twisted-stalk, spotted coralroot, wild sarsaparilla, Hooker’s orchid, gold thread. Hiking in the Lost Forty really is a trip back in time to before Minnesota was logged over.

In the course of writing One North Star, I also wrote a book about the bog (Big Belching Bog) and one about the prairie (Plant a Pocket of Prairie). I wanted to write a companion book about Minnesota’s forests but struggled to find a way in that would be both engaging and also specific. Because the Lost Forty is one of the few remaining stands of old growth pines in Minnesota, and because the story of how it got lost was fascinating, I began to write about it.

Mostly I concentrated on the plants and animals, with a nod to how the forest got lost. I remembered a sign at the entrance to the Lost Forty that talked about a surveying error. But my memory mis-remembered, and I wrote several drafts before realizing that the error was made not by timber cruisers, the people employed by lumber companies to estimate the amount of usable lumber in a certain area, but by land surveyors. This led me to research the fascinating world of the casdastral survey that measured off most of the land in the United States, step by step, acre by acre, section by section. The Bureau of Land Management has digital records that include the map and journal of the crew who surveyed what is now the Lost Forty. For some reason (there are several theories as to how it happened) they mis-surveyed part of the forest as a lake. Speculators and timber companies who studied maps weren’t interested in buying lakes, just forest, and so the site was overlooked for 76 years. I couldn’t track down the exact person who “found” the Lost Forty, but I did find a letter dated 1958 that requested a re-survey which discovered those virgin white pines.

Perhaps one of the biggest realizations for me working on this story was understanding that how we measure land reflects how we treat the land: as a commodity to be bought and sold, often with no attempt to understand the organic nature of the land itself. It made me so happy when one review noted that the book’s “implicit message [is] that the natural world is something more than a measurable commodity.”

I have always loved maps (although I am also frequently lost). Just pouring over the names of places fascinates me, as does knowing that maps are only an approximation of reality, and that sometimes maps deliberately lie. You can find the Lost Forty on maps now, no longer lost but protected for anyone to visit who wants to take a trip back in time. And it makes me think about what other wonders might not be on maps but still waiting to be found. v

Betsy Bowen, illustrator:

Betsy Bowen, illustrator:

When this manuscript came to me from the University of Minnesota Press, I eagerly took it on. I have lived on the edge of the northern Minnesota forest for over fifty years, and there are only a few places to see the really big, old trees. I’d had the experience of canoe camping in Canada and finding sections of the forest that felt like no one had ever seen it before, thick spongy moss, deep green light, and gigantic trees. There was a magical sense to it. My grandfather P. S. Lovejoy was a forester in the early 1900s and an early conservationist voice who made an effort to save some wild places for us all to experience. I loved visiting The Lost Forty and feeling like a little kid trying to put my arms around such a big tree!

I used acrylic paint on gessoed paper, first painting the whole page flat black, and then drawing with a chalky terra-cotta-colored Conté crayon. I had help from some present-day foresters to find the original old survey notes that I could page through online, and photos of the survey crew in 1882. My father, a civil engineer, was also a surveyor, still using the same equipment that Josiah used to survey The Lost Forty. I remember looking at the moon through his old brass transit. My mother was a cartographer in the 1930s and ‘40s, and I gained my love of maps from her.

I love the sense of discovery in Phyllis’s writing of this story. The book was great fun to work on. v

Our thanks to Phyllis Root and Betsy Bowen for sharing their creative process with us, a process that resulted in this important book. We hope you’ll treasure it as much as we do.

Can’t wait to see this book! I visited the lost 40 just last fall.…soooo interesting.

After reading this interview, I want to pack my backpack and make a trip up north to see the Lost Forty. Maybe this summer! With these two talented creators, I know this book is going to be a treasure.