This past February, my husband and I traveled to Cuba on an eleven-day tour. Near the end of the trip, we drove from the central city of Camagüey to visit a ranch. After a two-hour drive, our bus bounced down a long dirt road and passed under a wooden sign that resembled a gate in an old western, telling us we had reached “The King Ranch.” Sheep, goats, and cattle grazed on dry, scrubby brush, in fields that lined both sides of the road.

This past February, my husband and I traveled to Cuba on an eleven-day tour. Near the end of the trip, we drove from the central city of Camagüey to visit a ranch. After a two-hour drive, our bus bounced down a long dirt road and passed under a wooden sign that resembled a gate in an old western, telling us we had reached “The King Ranch.” Sheep, goats, and cattle grazed on dry, scrubby brush, in fields that lined both sides of the road.

We drew up near the ranch’s main building. The ranch manager who welcomed us was fluent in English. He told us that Mr. King — the same wealthy Texan who once developed a million-acre ranch in the U.S — had bought 40,000 hectares of land in Cuba before the Revolution. At its height, the ranch boasted 20,000 head. When Castro came to power, the ranch passed into government hands, as did all land and private businesses on the island. Now the ranch supports 3,000 animals and a village of about 130 people.

Our visit to the ranch included a small rodeo, where a few vaqueros, riding small cow ponies, competed in calf and bull roping as well as bull riding. One stocky cowboy managed to stay aboard a bucking bull for fifteen seconds before being tossed to the ground. He scrambled to his feet and dusted himself off, unhurt.

After the show ended, we climbed into horse-drawn wagons that carried us to the village. As we approached a circle of small, thatch-roofed cottages, a few kids ran along next to our carriages, calling out to us. Why weren’t they in school?

Before we could ask, our horses drew up in front of a tiny, two-room school building. We gathered in a garden outside, decorated with colorful, handmade sculptures of animals and insects. Our guide explained that the teaching principal had just been selected as Teacher of the Year for all of Cuba. This honor meant that the school would host a local district meeting the next day. School had been cancelled to allow a team of teachers and parents to spruce up the building, set up displays, and sweep out the two small rooms where children in grades K‑4 were educated. In a narrow hall, a parent was dusting and arranging a few dozen books on a narrow shelf that made up the school’s entire biblioteca.

An outside observer might think these children were deprived. After all, their homes were small simple structures, with dirt floors and thatched roofs. Except for the main ranch building, none of these homes were built to survive a hurricane. I also wondered how the school managed with so few books and materials. Yet the teaching principal (speaking through a translator) was proud of his school’s success. He spoke of the benefits children gain when different ages learn and work together. He also explained that parents are very involved in their children’s education.

Cuba prizes its children. The country boasts one of the world’s highest literacy rates. Children’s health and education are a top priority. Throughout our travels, we saw children who appeared healthy, well-fed, and happy. On school days, children wear uniforms according to grade level: red and white for primary school; yellow and white for middle school; brown and white for high school; and dark and light blue for higher education. Their uniforms are clean, bright, and serviceable.

Health care is free for all, new mothers can take a year’s maternity leave, and the state provides free daycare from six months to age five or six. Education is free, from kindergarten through university or technical school, and graduate school.

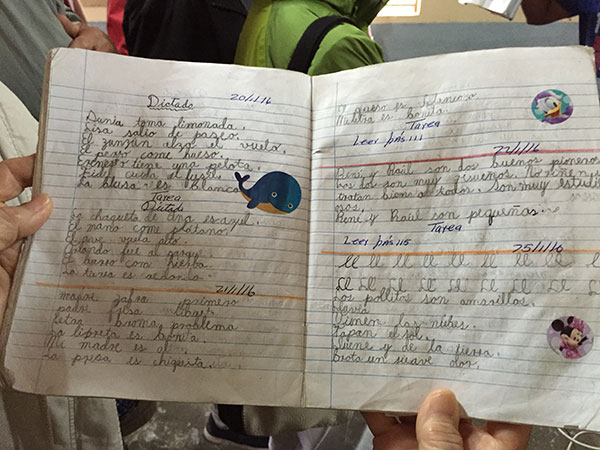

Although this village is twenty-one kilometers from the nearest town, nurses and doctors visit regularly, and ranch children receive the same education and follow the same curriculum as their peers in city classrooms. Twice a week, teachers make the long trip to give lessons in art, music, and computer science. The principal showed us a first grade notebook where a child had written long paragraphs in perfect cursive.

Displays on the wall demonstrated science projects and geography. Children leave the ranch in fifth grade to board with families in a larger town, four nights a week. There, their learning continues, through high school and beyond if that is what they choose.

After our tour, I walked back to the main house with our guide and the vaquero who had demonstrated bull riding. I learned that he and his daughter, now 17, were both born in the village and educated at the village school. His daughter was now finishing high school and would enter medical school in the fall. He was proud of her accomplishment, but he spoke as if it wasn’t unusual.

Of course, Cuba has enormous economic problems. Though citizens are well-educated, they work for paltry salaries and may not find jobs that allow them to use their expertise and training. Their lives are constricted in ways that we would find oppressive. But as our bus drove away from the ranch, I thought of the stunning and inspiring art exhibits, concerts, and dance performances we had seen in every city on our tour, which demonstrated the value Cuba places on the arts. This was in sharp contrast to our schools, where the arts often disappear when budgets are tight. I thought of city schools in America with overcrowded classrooms that lack basic materials, and teachers who are poorly paid and disrespected. What if our country valued its children, their health, nutrition, and education, as highly as Cubans do?

The Cubans we met were warm, welcoming, and informed. They asked knowledgeable questions about our upcoming elections. Cubans hope — as we do — that the rapprochement begun by President Obama will continue to grow and heal the rift between our two countries. Many Americans like to boast that our nation is the wealthiest in the world. Still, we have much to learn from this fascinating, crocodile-shaped island.

Wonderful report Liza. It’s heartbreaking to think of what we could do, if only we had the will to do it, if only we cared about our children that much.

Such a clear, enviable in a way, picture, Liza. Thank you!

So lovely. Thank you for this, Liza!