Serendipity is one of my favorite words. I love its dancelike sound and the way it trips off the tongue. According to my dictionary, serendipity means “the faculty of making fortunate discoveries by accident.”

I find the etymology of words fascinating. Even as a child, I liked to study the maps that show the relationship and origins of Indo-European languages. (Here’s an animated version.) So where does the word serendipity come from?

My American Heritage dictionary traces the word’s origins to the English writer Horace Walpole, who supposedly coined the word in a 1754 letter to a friend. Walpole described a Persian fairy tale he had read, concerning three princes from Serendip. The brothers — highly accomplished, smart, and artistic — were banished from their kingdom by their father, the king. Wandering in a foreign land, they encountered a merchant who had lost his camel. The brothers used powers of deduction — which we now associate with detective fiction — to find the camel. Walpole said, “They were always making discoveries, by accident and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of.”

Things they were not in quest of. This phrase made me think of other famous discoveries that happen by accident — such as the penicillin mold that grew when Alexander Fleming left a Petri dish on his windowsill by mistake, or the burrs that attached themselves to George de Mestral’s clothes on a mountain hike, giving him the idea for Velcro. Serendipity also makes me think about moments in our writing lives when incidents, events, and ideas merge to trigger a Eureka! moment.

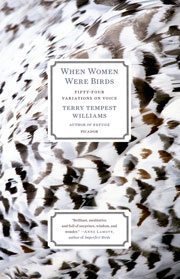

Three years ago, at a Hamline University summer residency, I opened a new notebook late one night, and scrawled these words: “The Last Garden.” The title had come to me after I read the first two entries in Terry Tempest Williams’ brilliant book, When Women Were Birds, a gift from Phyllis Root. Williams wrote the memoir after her mother died and she uncovered a shocking truth about her life. I had recently lost both parents, so Williams’s topic pulled me in. I was also drawn to the book by its format: a series of short vignettes, forking off a single idea like branches on a tree. Vignettes seemed like a manageable, less daunting way to deal with personal subject matter. But wait — since when was I planning to write about gardens?

Three years ago, at a Hamline University summer residency, I opened a new notebook late one night, and scrawled these words: “The Last Garden.” The title had come to me after I read the first two entries in Terry Tempest Williams’ brilliant book, When Women Were Birds, a gift from Phyllis Root. Williams wrote the memoir after her mother died and she uncovered a shocking truth about her life. I had recently lost both parents, so Williams’s topic pulled me in. I was also drawn to the book by its format: a series of short vignettes, forking off a single idea like branches on a tree. Vignettes seemed like a manageable, less daunting way to deal with personal subject matter. But wait — since when was I planning to write about gardens?

That same morning, as we discussed our workshops, Phyllis told me that she planned to ask her students that great question: “What would you write if you knew you could not fail?” It made me think of Mary Oliver, who demands, in her poem “The Summer Day”: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do/with your one wild and precious life?”

For years I had tried to write a memoir about my relationship with my grandmother, and the Vermont house where I spent my childhood summers, but I couldn’t find a unifying thread. When I wrote those words — “The Last Garden” — I realized that gardens — and gardeners — could provide that unity. My husband and I had just purchased a sweet house, down the road a mile from my grandmother’s old place. The property came with overgrown lilacs and tangled, overgrown gardens that concealed peonies, foxgloves, and an asparagus bed. Though I have gardened all my life, I realized this would be the last garden I would create from scratch.

Since that moment at Hamline, the focus of my writing has changed dramatically. In addition to the memoir, I’ve been writing essays and articles about nature and the environment. I’m working on two non-fiction projects, focused on environmental subjects, with my dear friends Phyllis Root and Jackie Briggs Martin. All thanks to serendipity.

Perhaps the best thing about serendipity is that we can’t explain how it happens. Who could predict that the loss of my parents, the gift of a wise book written in an appealing form, and the right question at the right time — would coincide with ideas I was “not in quest of”?

Meanwhile, as I wrestle with the memoir’s final vignettes, I can’t help thinking of that missing camel that — as the Serendip brothers predicted — was lame, blind in one eye, and lumbered under the weight of a leaking sack of honey, a bag of butter, and a pregnant woman.

Meanwhile, as I wrestle with the memoir’s final vignettes, I can’t help thinking of that missing camel that — as the Serendip brothers predicted — was lame, blind in one eye, and lumbered under the weight of a leaking sack of honey, a bag of butter, and a pregnant woman.

Uh oh. Doesn’t that sound like a picture book, waiting to happen?

Wonderful Liza! I did not know the origin of “serendipity”– the three brothers from Serendip. And I love the image of the camel, lame, blind in one eye, lumbering along with a leaking sack of honey, a bag of butter and a pregnant woman.

I love this Liza. The word serendipity has always been on my list of favorites — both because of how it sounds and because of its meaning. It suggests that their is order in the world beyond our conscious knowledge. Beyond all that, it was great to hear what you’re up to in your writing life. When you get that memoir finished I’ll be one of the first in line to read it.

Thank you, friends, for your comments. I hadn’t seen the camel photo until today – this one looks as if it has something very definite – and possibly contrarian– to say.

This is beautiful and interesting, Liza. How fortunate we are to have your work in the world, serendipitous or not, (and the gardens, too)!

Thank you for this, Liza. So wonderfully full of life!

What a powerful question, “What would you write if you knew you could not fail?” Thanks for passing Phyllis’ question along to the rest of us, Liza.