A Picture Book Excursion through City Park History

Spring is in the air, and we’re pulled outdoors to wander in our favorite city parks. Ducks are dabbling; frogs are trilling; the apple trees are bursting into bloom. Everywhere, it seems, children frolic and neighbors wave. It’s been a long winter, but our cities are alive. Now is the perfect time for a picture book excursion through city park history. It’s a fascinating journey — thanks for coming along!

Spring is in the air, and we’re pulled outdoors to wander in our favorite city parks. Ducks are dabbling; frogs are trilling; the apple trees are bursting into bloom. Everywhere, it seems, children frolic and neighbors wave. It’s been a long winter, but our cities are alive. Now is the perfect time for a picture book excursion through city park history. It’s a fascinating journey — thanks for coming along!

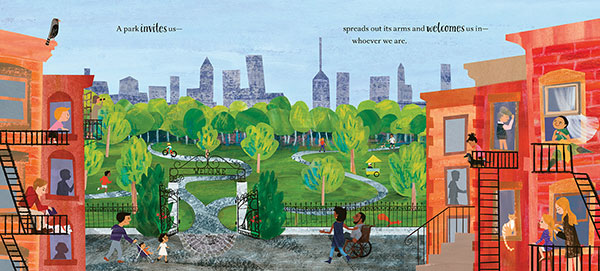

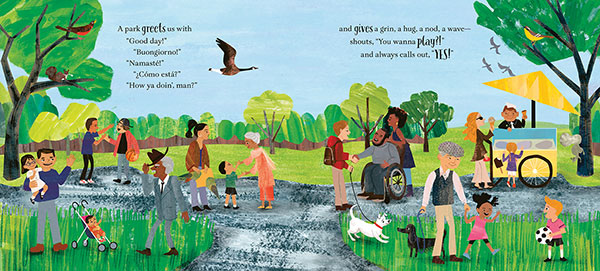

For many of us living in a city or town, it’s hard to imagine life without parks. Our parks give us relief from the work- and school-day chores, the noise and hurry of the city, and the isolation of our modern lives. Parks bring us together. They help our neighborhoods feel like homes. They give us places to unwind, exercise, fly kites, celebrate, meditate… From babyhood to old age, we are welcome in the parks — whoever we are. What a rare and important tradition. Our parks deserve celebrating. It’s why I wrote A Park Connects Us.

We need these shared, green spaces more than ever right now. After all the divisiveness of the last several years and the heartache and separation of the pandemic, we need safe, kind places to be together. We need places where we can step outside of our bubbles into our real towns and cities — the ones with birds and sunshine, the ones we share with people who don’t necessarily look or talk or think or pray like us, but where nevertheless children call out, “You wanna play?!” and grown-ups smile and say, “Good day.” In the parks, it doesn’t matter who we are or where we come from or how much money is in our pockets. We all belong. We’re all connected.

Once upon a time, however, not so very long ago, most North American cities had no parks. Dirt and concrete stretched for miles. Hardly any trees grew. Factory soot, coal ash, and wood smoke fouled the air. Only the very richest people had access to nature — on their secluded, private estates, gated away from the densely crowded cities. Meanwhile, millions of middle- and working class residents were squeezed into landscapes of buildings and industry. Sometimes families found refuge in cemeteries, which were often the only green spaces to stroll, and children played in the dusty streets. Thankfully, visionary city people in the latter half of the 1800s joined together and worked to change this.

The urban parks movement began in earnest with the creation of New York City’s Central Park, and, several years later, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. America’s first landscape architects, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, were hired to design these parks. They aimed to grow them into glorious expanses that would feel wild and green and offer city people of all walks chances to connect with nature and each other.

The urban parks movement began in earnest with the creation of New York City’s Central Park, and, several years later, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. America’s first landscape architects, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, were hired to design these parks. They aimed to grow them into glorious expanses that would feel wild and green and offer city people of all walks chances to connect with nature and each other.

In actuality, Central Park and Prospect Park (like many parks that came later) were engineered landscapes, with rolling hills shaped out of rubble, babbling brooks artificially pumped and channeled, and trees rooted and grasses sown into choreographed woodlands and pastures. (Both parks even had flocks of grazing sheep in the early years!) These projects required thousands of workers and took several years to complete, but when they were finished, they were works of art.

In actuality, Central Park and Prospect Park (like many parks that came later) were engineered landscapes, with rolling hills shaped out of rubble, babbling brooks artificially pumped and channeled, and trees rooted and grasses sown into choreographed woodlands and pastures. (Both parks even had flocks of grazing sheep in the early years!) These projects required thousands of workers and took several years to complete, but when they were finished, they were works of art.

As inspiring as these early park projects were in many ways, the history of Central Park, in particular, is not without controversy. Before the park was made, most of the miles-long rectangle of land was rocky, swampy, and treeless. The land housed pig farms, slaughterhouses, and glue-making factories. However, there were also people (mostly with little political power) living on various parts of the land in scattered homes and a few small villages. Notably, several acres of what became Central Park belonged to one of the first villages of free Black Americans, Seneca Village. By the 1850s, Seneca Village was a mixed-race community composed mostly of Black residents, but also Irish and German immigrants. In 1857, their well-loved neighborhoods were claimed by the city in the first use of eminent domain in U.S. history. Residents were forced to move, so that the park could be built. (Central Park may have been one of the first places in the U.S. where parkland was acquired partially at the cost of vulnerable members of the population; unfortunately, it also wasn’t the last.)

Ultimately, after opening, Central Park and Prospect Park became increasingly (and enormously) popular. In the 1860s and early 1870s, millions of city people of all classes and backgrounds flocked to the parks to meander, picnic, and play. These vast, nature-filled parks gave New Yorkers relief from the noise, hurry, and pollution of the industrial city, and they sparked a movement.

From there, a decades-long era of park creation rippled across the U.S. and Canada. During this time, cities of all sizes planned and built expansive parks of their own. Frederick Law Olmsted designed hundreds of these parks and championed a democratic vision for shared public space (and for cities planned around shared space) that shaped the parks’ movement and benefits us still today.

From there, a decades-long era of park creation rippled across the U.S. and Canada. During this time, cities of all sizes planned and built expansive parks of their own. Frederick Law Olmsted designed hundreds of these parks and championed a democratic vision for shared public space (and for cities planned around shared space) that shaped the parks’ movement and benefits us still today.

Throughout these years, trees were planted by the millions. Park makers and city leaders hoped that tree-filled parks and tree-lined streets would become “the lungs” of cities, filtering polluted skies and giving city people fresher air to breathe. Meanwhile, more and more parks were strategically built along lakes and waterways, helping to protect drinking water, while also preserving shared beauty.

Throughout these years, trees were planted by the millions. Park makers and city leaders hoped that tree-filled parks and tree-lined streets would become “the lungs” of cities, filtering polluted skies and giving city people fresher air to breathe. Meanwhile, more and more parks were strategically built along lakes and waterways, helping to protect drinking water, while also preserving shared beauty.

While the vast historic parks built during the late 1800s served many, not everyone lived near enough to make regular use of the parks. Thus, a movement for smaller, more accessible parks began in the early 1900s. Neighborhood parks were first embraced by the people of Chicago. Their aim was to give everyone — especially the working classes — in all parts of the city, convenient green spaces to gather, rest, and play. These new parks were filled with purpose-built things for children and families to enjoy, like playgrounds (a new invention!), ball fields, swimming pools, and basketball courts. New park buildings offered community games and classes, running water for showers, and sometimes even hot meals and medical services. Neighborhood parks were so successful in Chicago, they inspired another wave of park creation in cities and towns across the U.S. and Canada.

Like most every American story, the park story is an imperfect one, filled with both triumphs and mistakes. It’s worth remembering that the parkland on which we stroll and play is the traditional land of myriad Indigenous Peoples, and that there is still more work to do to make access to parks equitable. Today, however, parks remain some of our most valuable institutions. They’re the connective tissue of healthy communities — important for our personal wellbeing, but also our shared joy. One hundred and fifty years after the urban parks’ movement began, we have tens of thousands of public parks in North America, beautifying and bringing together our cities and towns. And they belong to all of us.

So appreciate, use, and celebrate the parks. Teach the children to love and share them. We are ever so lucky to have our parks and must carry on creating and caring for these havens, so that whoever and wherever we are, we will always have green places to gather, rest, and play.

Continue the excursion through city park history with these beautiful picture books:

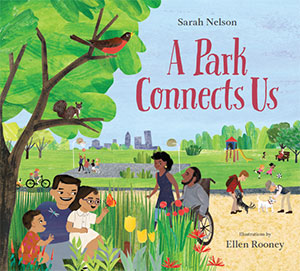

A Park Connects Us

By Sarah Nelson; illustrated by Ellen Rooney | Owlkids Books, 2022

This love letter to city parks celebrates the many ways parks connect us to neighbors and nature. Back matter shares more moments of park history and highlights parks successes around the world.

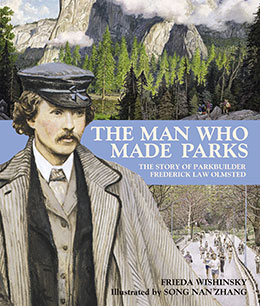

The Man Who Made Parks

By Frieda Wishinsky; illustrated by Song Nan Zhang | Tundra Books, 2009

A beautifully illustrated biography of Frederick Law Olmsted tells the life story of the man who designed hundreds of our most beloved city parks and public spaces.

A Green Place to Be: The Creation of Central Park

By Ashley Benham Yazdani | Candlewick Press, 2019

Learn the story of the creation of New York City’s Central Park in greater depth through lively text and pictures that that will help children connect with this park’s history.

Parks for the People: How Frederick Law Olmsted Designed America

By Elizabeth Partridge; illustrated by Becca Stadtlander | Viking Books for Young Readers, 2022

A biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, highlighting the work Olmsted did on three iconic American landscapes: Central Park, Yosemite National Park, and the U.S. Capitol Grounds.

The Tree Lady

By H. Joseph Hopkins; illustrated by Jill McElmurry | Beach Lane Books, 2013

Enjoy the heartening story of park maker Kate Sessions, the Mother of San Diego’s Balboa Park, who in the early 1900s transformed the city’s barren park into a tree-filled sanctuary.

Excellent! Thank you so much. So sad about the immoral use of emminent domain. Ah, that we could find a balance in sharing spaces and respecting private places.