by Liza Ketchum

This week, while I prepared for a talk at AWP (Association of Writing Programs) on writing non-fiction biographies for kids, I thought about how I enjoy researching both nonfiction and fiction titles. Yet a gulf often separates the two genres. In my local library, you turn right at the top of the stairs for the nonfiction stacks and left to peruse the novels. The same division holds true in the children’s room downstairs. In my own writing studio, nonfiction books fill one shelf, while novels threaten to topple another. Yet elements of one often bleed into the other.

I have always been fascinated by the role of women in American pioneer history. My first YA novel, West Against the Wind, drew heavily on 19th century diaries, letters, and newspapers. The facts of the time shaped and inspired the story. A few years later, I was asked to write a nonfiction book on the California Gold Rush. For that book, I drew both on primary sources I’d used in my novel, as well as on new material I uncovered in such wonderful resources as The Huntington Library in San Merino, CA.

An editor at Little, Brown was interested in the story of the child performer Lotta Crabtree, whom I profiled in The Gold Rush. Could I write about eight adventurous pioneer women like Lotta, who “broke the rules” and made history during that time? I agreed and ended up with my nonfiction book Into a New Country.

By now, I had a huge box of notes and images on the pioneer period. I thought I was finished with that era, but the dance continued. In the process of writing The Gold Rush, I uncovered information about children who also caught “gold fever.” They panned for gold alongside their parents, helped them run stores or restaurants, and performed in saloons — where some girls ran hairpins along cracks in the floorboards to collect gold dust.

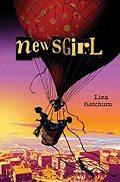

Two small items from my research went straight into my Idea File. One was that gangs of boys in San Francisco could make more money — selling six-month-old East Coast newspapers on the street — than their parents, who struggled to survive in that hurly-burly town. Another was a newspaper item about a boy who survived an accidental balloon ascent. He became the first person to see the bay area from the air.

Those stories — and some nagging questions — stayed with me. What if a girl wanted to be a newsboy? What if the boys wouldn’t let her in? And what if her family arrived in San Francisco penniless: could she help them survive? And what if she tried to get a news scoop on a balloon ascent?

I wrote Newsgirl to answer those questions.

I wrote Newsgirl to answer those questions.

Whether I write nonfiction or fiction, each informs the other. I use fictional techniques in nonfiction. I want to grab the young reader, pull him or her into the story with action, dialogue, strong character, and significant detail. I want to appeal to the son of a writer friend who asked his mom, “When are you going to write one of those books where, you know, something happens on every page?”

At the same time, I use techniques and information from nonfiction to anchor my novels in time and place. My most recent YA novel, Out of Left Field, is not historical fiction per se (though 2004 may feel like ancient times to some young readers). The Vietnam War casts shadows over the novel. Though I lived through that era, I didn’t know enough about men who fled the country for Canada, as my protagonist’s father did. I tracked down memoirs of draftees and enlisted men who fled the country and read accounts of life on the run. My friend, the Canadian writer Tim Wynne-Jones, suggested books about American resisters who lived in Toronto during those times. I watched a video of the draft lottery that took place in 1969, an event that determined the lives — and deaths — of thousands of young men. And I read and reread Tim O’Brien’s book, The Things They Carried, itself a stunning fusion of fiction and memoir.

While Brandon, my narrator, is invented, I had the actual Red Sox schedule at hand as I wrote. Brandon follows the 2004 season with as much devotion as I did that year. When Brandon sees David Ortiz slam his game-wining hit in the 14th inning of the Sox-Yankee game, the pandemonium in the stands is real, as are the smells, the sounds, the energy of a ball park when fans realize the team could win it all — for the first time in eighty-six years.

My friend and colleague, Phyllis Root, asks: “Is the line growing more malleable between speculation and fact?” Certainly young readers need to know the difference between what is real and what is invented. But perhaps the separation between non-fiction and fiction is arbitrary. Maybe I’ll mix the two genres on my own shelves. Who knows what sparks might fly if these books end up dancing together?

Fabulous piece and exciting new forum!