If you’ve ever dipped a toe into the children’s book publishing world, you’ve probably heard cautionary tales about writing in rhyme. In short, most insiders say, “Please don’t rhyme.” They warn us that we may think our rhyming is something special but, likely, it’s not. “Editors don’t want to read your tired rhymes,” these experts say. “Write something else.”

For many years, I actively tried to suppress my rhyming impulses. But sometimes rhymes just bubble up from someplace irrepressible inside me. An inner toe-tapping beat comes drumming. A lilting melody sings forth. And as of today, against all logic, I have more rhyming books in print and production than anything else — despite that the majority of my portfolio does not rhyme. If anything, I’m a little worried about getting typecast. What is going on here anyway?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this question and about rhyming cautionary tales for the last several years, and I have some theories. First and most importantly, there is this. Although many of us learned to write in rhyme in elementary school, great rhyming is deceptively difficult to do. It’s incredibly easy, on the other hand, to get rhyming all wrong. (I know because I do this sometimes, too.) When done poorly — without rhythm, employing words that are predictable or forced — rhymes can make us cringe with awkwardness. Bad rhymes hurt editors’ ears and exasperate their literary sensibilities. Understandably, these beleaguered gatekeepers of the publishing industry wish that we would please stop the torture.

Or so I imagine…

That said, many parents, teachers, and children continue to love and seek out rhyming books, and editors and publishers know this, too. Good rhymes can be magical. They’re fun to hear; they tickle our ears. They make us laugh with silly sounds or bounce to chirpy melodies. They can lull us like rocking waves or sway and comfort us like mamas’ arms. Good rhymes also stay with us long after they are read or heard.

There is a story in my family about two-year-old me, plopping onto a stool at Grandma and Grandpa’s house (Miss Muffet-like?) to give this spontaneous recitation:

“Little Miss Muffet sat on a tuffet eating her curds and whey.

Along came a spider and sat down beside her

…and bumped her on the head.”

I’m not sure what happened with that last line. (Had I recently bumped my head? Perhaps I was just going for a big finish.) Yet despite not knowing what a tuffet was or curds and whey, my little toddler mind got the words (mostly) right — no doubt because of the pleasing rhymes.

Good rhymes, like good songs, are catchy and memorable. I mean, who among us hasn’t sung I Want to Know What Love Is up and down the frozen food aisle with the grocery soundtrack? (Oh, say it isn’t only me.) These radio hits of yesteryear are emblazoned on our neural pathways, in part, because of their infectious rhymes. Even when we wish we could forget them, we cannot.

Rhymes can definitely be annoying. Too many can be cloying. Yet year after year, rhyming books still sell because when done well, rhyming can be sweet, surprising, happy, hilarious, bright, beautiful, musical, soothing, delicious to say, luscious to hear … and kids want to listen again and again and memorize the lines and say them with us.

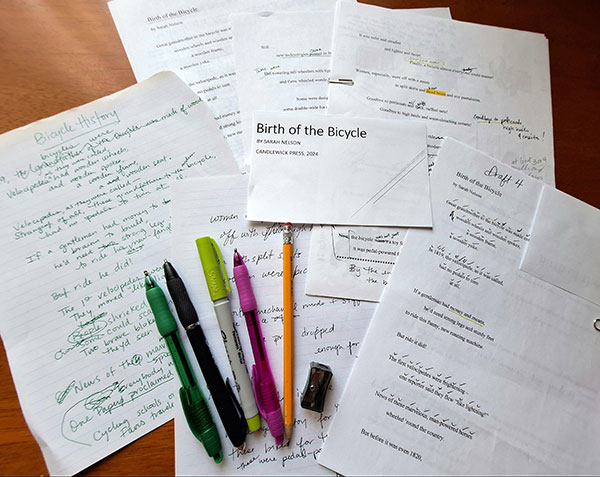

Therefore, if we wish to rhyme, we authors simply have to work devotedly at rhyming very, very well. For me, every draft is a new puzzle and a challenge. Sometimes, I write fifty not-very-good rhymes for every exceptional rhyme. The story must always be the anchor and take precedence even over the cleverest lines. I abandon some projects entirely and finetune others for years. Sometimes, a little rhyme works far better than a lot; other times the rhymes keep tumbling. I don’t know why.

While working in rhyme, I say my lines out loud a thousand times — I say them while I cook and clean and drive to work, while I’m drifting off to sleep, while I’m standing in the shower. I recite them to my husband, to the closet, to the flowers. Outside, alone, to the beat of my feet, I also leave them on the street. (If I’m lucky, when I’m walking, lines get comfortable like talking.) Then I read them and record them, rethink, reword, revise them … again, again, again, again … until the lines and the rhymes (I hope) are as smooth as melted butter.

Still, and as my wise, long-suffering agent often reminds me, many editors won’t even look at rhyme. So if you don’t love rhyming or it doesn’t come naturally to you, please refer to paragraph one and write something else. Honestly, it’s almost certainly the much more sensible thing to do.

But if you are a little like me, and your impractical, lyrical heart persists to thump and thrum? Well, I say … rhyme on.

Love this. So fun!

Thanks so much. Happy you enjoyed it!

Truth in every word!

Ha! I love this: “Great rhyming is deceptively difficult to do. It’s incredibly easy, on the other hand, to get rhyming all wrong.”

Definitely a better way to caution writers than Just Say No to Rhyme.

Thanks so much, Lynne.

Thanks, Adrianne. 🙂

Very well said, Sarah. I Couldn’t agree more.

Thanks so much, Praveen. 🙂

Can you suggest someone to read my rhyming stories to let me know if they are closer to being all right than all wrong? I’ve never had anything published, but I have written lots of rhyming short stories to amuse myself. I really enjoyed your article.

Hmm. Good question. (Sorry for the delay!) For me, my writing group is always the place to start. They are supportive, yet honest with me when my rhymes are not landing right. If you don’t have a writing group (and you’re writing for children), your local chapter of SCBWI could help you connect with one. Also, sometimes the Loft Literary Center offers a class specifically about writing in rhyme (if you happen to be in the Twin Cities)… Another thing I also always do is ask a few friends to read my stories or poems out loud to me. Sometimes the lines or rhymes… Read more »