“There is not such a cradle of democracy upon the earth as the Free Public Library, this republic of letters, where neither rank, office, nor wealth receives the slightest consideration.” —Andrew Carnegie

Libraries in the USA are at mission critical. Those who went before us worked hard to establish free public libraries so we could have access to what we need to know. How can we let their legacy erode?

We’ve already seen our public school libraries damaged by budget shortfalls in which libraries are deemed non-essential and degreed librarians are considered easily replaced by a volunteer.

Public libraries have suffered as well via consolidation, replaced by pick-up-your-book kiosks, and outright closure.

For readers, it is understood how vital libraries are as a free source of education, essential services, and entertainment that might otherwise be too expensive for families and individuals. Beyond books, public libraries offer free programming in education, crafting, music and dance, citizenry, and business. Some libraries have become a place to check out seldom-needed but important items like fishing rods, electric drills, sewing machines, and gardening tools.

Reading is still at the heart of the library. The ability to learn, whether by fiction or nonfiction, and the privilege of asking a librarian who can help you find what you need and what you don’t yet know that you need — that is a library. No computer algorithm, no matter how well-meaning, can take a librarian’s place.

Many of us take our public library for granted. We walk a few blocks, ride our bikes, drive a few miles or 30 miles to check out books and magazines. We can call the staff on the phone to make sure they know what we’re looking for and have it. If they don’t have it, they can order it from a library far, far away. This is one of the most reliable services of being an American citizen.

This access to information and resources was hard-won. The generations before us recognized how vital books and reading are to a healthy, citizen-engaged country.

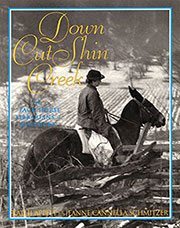

In Down Cut Shin Creek: the Pack Horse Librarians of Kentucky by Kathi Appelt and Jeanne Cannella Schmitzer (Harper Collins, 2001), we learn the riveting true story of women, primarily, who were hired by the Work Projects Administration (WPA) in 1935, during the height of the Depression, to ride horses or pack mules to the often inaccessible small communities and individuals of eastern Kentucky. Eventually these librarians would serve more 100,000 people in 30 counties as part of the Pack Horse Library Project. It’s an inspiring book. Reading the account of how important these librarians were because they knew their communities, their readers’ tastes, and felt a sense of duty … it’s easier to understand why libraries have been so vital in America.

In Down Cut Shin Creek: the Pack Horse Librarians of Kentucky by Kathi Appelt and Jeanne Cannella Schmitzer (Harper Collins, 2001), we learn the riveting true story of women, primarily, who were hired by the Work Projects Administration (WPA) in 1935, during the height of the Depression, to ride horses or pack mules to the often inaccessible small communities and individuals of eastern Kentucky. Eventually these librarians would serve more 100,000 people in 30 counties as part of the Pack Horse Library Project. It’s an inspiring book. Reading the account of how important these librarians were because they knew their communities, their readers’ tastes, and felt a sense of duty … it’s easier to understand why libraries have been so vital in America.

A congressman from Kentucky, Carl D. Perkins, sponsored the Library Services Act in 1956 “that made the first federal appropriations for library service.” More than likely, he was influenced by a Pack Horse Librarian while he taught in rural Kentucky.

For a picture book about the Pack Horse Librarians, read Heather Henson’s That Book Woman, illustrated by David Small (Atheneum, 2008). Written by a Kentucky native, this story of Cal, living high in the Appalachian hills, depicts a young boy who wants nothing to do with reading until he realizes the extraordinary lengths his Pack Horse Librarian is achieving to bring him books.

For a picture book about the Pack Horse Librarians, read Heather Henson’s That Book Woman, illustrated by David Small (Atheneum, 2008). Written by a Kentucky native, this story of Cal, living high in the Appalachian hills, depicts a young boy who wants nothing to do with reading until he realizes the extraordinary lengths his Pack Horse Librarian is achieving to bring him books.

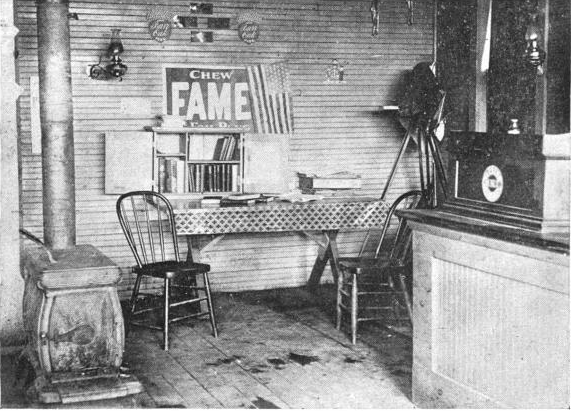

In northern climes, Stuart Stotts wrote the marvelous Books in a Box: Lutie Stearns and the Traveling Libraries of Wisconsin (Big Valley Press, 2005). Lutie Stearns grew up near Milwaukee, reading all the time. She is drawn to library service where, thankfully, she has big ideas. She teams up with Frank Hutchins (another big idea person, he started the Wisconsin State Forest Department, and introduced Easter Seals to the Anti-Tuberculosis Association) to create traveling libraries.

In northern climes, Stuart Stotts wrote the marvelous Books in a Box: Lutie Stearns and the Traveling Libraries of Wisconsin (Big Valley Press, 2005). Lutie Stearns grew up near Milwaukee, reading all the time. She is drawn to library service where, thankfully, she has big ideas. She teams up with Frank Hutchins (another big idea person, he started the Wisconsin State Forest Department, and introduced Easter Seals to the Anti-Tuberculosis Association) to create traveling libraries.

Melvil Dewey (he of the Dewey Decimal System) introduced publicly-funded traveling libraries in New York State in 1893. (The first traveling libraries were likely those in Scotland and Wales in the early 1800s, but they were part of a schooling system.)

The next year, Lutie and Frank petitioned lumber baron and Wisconsin state senator James Stout to fund traveling libraries in Dunn County. They wanted him to introduce a bill in the legislature to fun the Wisconsin Free Library Commission. You must read this book for the engrossing experiences Lutie encountered as she tried to establish traveling libraries, books in a box, around the state in post offices and stores.

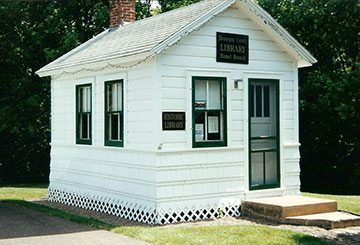

Later, Lutie would help citizens apply for funds from Andrew Carnegie to construct a library. These Carnegie libraries, some of which are still in use, brought education and entertainment to generations of citizens, taxpayer supported but otherwise free, throughout the United States. Lutie Stearns could celebrate the growth of books-in-a-box to full-fledged libraries through her persistent efforts and those of Frank Hutchins.

“The desire to have a good influence and a decent place to go, instead of the many saloons and dance halls, led me to visit one community no less than twelve times before I could get the town president, also owner of a dance hall, to appoint a library board.” (Lutie Stearns, Books in a Box, pg 49)

Twelve times? That’s determination.

Can we do less?

MORE RESOURCES

“The earliest libraries-on-wheels looked way cooler than today’s bookmobiles,” by Rose Eveleth, Smithsonian.com

“Traveling libraries,” by Larry T. Nix, Library History Buff