Books swept me away, one after the other, this way and that; I made endless vows according to their lights, for I believed them. (Annie Dillard, An American Childhood)

It’s hard to say which came first: did I adopt traits of the main character in certain books I read, or did I gravitate towards those books because I already had those traits? One thing I know is that I loved to read and because I was a reader I became a writer. Even today, I can’t wait to get my work over with so I can read.

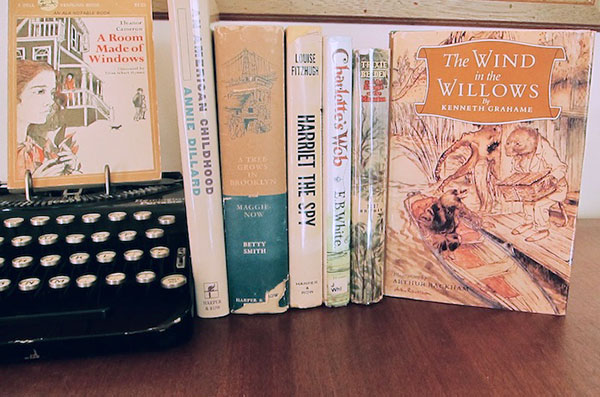

In no particular order, here are the books on my shelf that I see myself in.

An American Childhood by Annie Dillard. I didn’t come upon this book until it was published in 1987. I’d loved Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and my copy is a first edition hardcover. I’ve re-read it several times. This is my favorite passage:

“Children ten years old wake up and find themselves here, discover themselves to have been here all along … They wake like sleepwalkers, in full stride; they wake like people brought back from cardiac arrest … in media res, surrounded by familiar people and objects, equipped with a hundred skills. They know the neighborhood, they can read and write English, they are old hands at the commonplace mysteries, and yet they feel themselves to have just stepped off the boat … to lodge in an eerily familiar life already well under way.”

I woke up when I was ten years old, too. I had just been to a country funeral and after I stuffed myself with corn pudding and coconut cake, I walked up the road, past the cemetery, to look out over the rolling fields of Shenandoah County, Virginia. I stared at an old stone house and right then, I woke up. I knew a bunch of things: that I was meant to be living here and not Fairfax County, that I loved this land, that the old stone house was probably the site of a murder and I would find out what happened.

Which leads me to my second book, Trixie Belden and the Secret of the Mansion by Julie Campbell. My detective career began with the Trixie Belden series. I never did find out what happened in the old stone house, if anything, mainly because it was a hundred miles from where I lived, but I could solve mysteries at home! All I needed was a rich friend and an old house to explore:

“Crabapple Farm, Trixie reflected, was really a grand place to live, and she had always had a lot of fun there, but she did wish there was another girl in the neighborhood. The big estate, known as the Manor House, which bounded the Belden property had been vacant ever since Trixie could remember. There were no other homes nearby except the crumbling mansion where queer old Mr. Frayne lived alone.”

I was not a cheerful child. I was bossy and not particularly likeable. I wanted other kids to play whatever game I’d invented because my ideas were better. Clearly, I wasn’t overloaded with friends. But when I read Harriet the Spy, I felt relieved, validated, even. Harriet was like me: she had an agenda, she liked spying, and she kept a notebook (though I never thought to combine spying and writing). Harriet’s New York City world was nothing like mine, yet I identified with her. I was misunderstood, too. Why couldn’t I go my own way, I’d argue with my mother. Well … because I was only eleven. Like Harriet, I eventually learned to rein in my ambitions and occasionally think of other people.

“WHY DON’T THEY SAY WHAT THEY FEEL? OLE GOLLY SAID ‘ALWAYS SAY EXACTLY WHAT YOU FEEL. PEOPLE ARE HURT MORE BY MISUNDERSTANDING THAN ANYTHING ELSE.’ AM I HURT? I DON'T FEEL HURT. I JUST FEEL FUNNY ALL OVER.”

Although I craved adventure, I was a homebody at heart, and for reasons I’ve never understood, a worker-bee. At age nine, I had an agenda to “do my work.” Former classmates who knew me in fourth grade have told me this.

I came to The Wind in the Willows as an adult, too, a book I wish I’d read as a kid. I’m Mole, the character with the approach/avoidance complex. At the beginning of the book, Mole is busy spring-cleaning when suddenly he breaks bad, as my mother used to say. He leaves the dust mop and meets Rat and they have all sorts of adventures. Mole is happy to have a friend and do exciting above-the-ground things. But his home calls to him:

“It was one of those mysterious fairy calls from out of the void that suddenly reached Mole in the darkness, making him tingle through and through with its very familiar appeal, even while as yet he could not remember what it was. He stopped dead in his tracks, his nose searching hither and thither in its efforts to recapture the fine filament, the telegraphic current, that had so strongly moved him. A moment, and he had caught it again, and with it this time came recollection in fullest flood. Home!”

Charlotte’s Web made me wish there was a spider to save one of our pigs. We raised two hogs every year to kill and eat. I learned early on not to name the piglets we bought each spring. Though I’d like to be calm, clever Charlotte, who sacrifices her life, I know I’m more like Wilbur, the drama pig. When the sheep tell Wilbur what his fate will be, he puts on quite a show. I’m the same the way with almost any bad news — the world is coming to an end!

“‘Stop!’ screamed Wilbur. ‘I don’t want to die! Save me, somebody! Save me!’” [Garth Williams’ illustration of this scene is priceless.]

I read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn when I was twelve. I don’t know if my sister gave it to me to read, or if I just fell upon it in the library, but Betty Smith’s novel changed my life. I was Francie Nolan. I didn’t live in a tenement in 1912 Brooklyn. I didn’t know what a fire escape was or an air shaft. But I was Francie and she was me. We both loved the library. We both longed to own a real book (I had cheap Golden Books and Trixie Belden mysteries and Francie tried to copy a book in a cheap notebook by hand). After my weekly visit to the library, I read my book lying on the glider in the breezeway in the summer, or across my bed if it was winter, often while eating a box of Lemonheads:

“As she read, at peace with the world and happy as only a little girl could be with a fine book and a little bowl of candy, and all alone in the house, the leaf shadows shifted and the afternoon passed.”

The last book on my shelf I read at the age of 19, a year after I’d graduated from high school. A Room Made of Windows by Eleanor Cameron came out in 1971, with interior illustrations by Trina Schart Hyman. Chapter One opens with a spot illustration of a long-haired girl, sitting at a desk in front of a bank of windows, writing furiously in a notebook. Although I was working at my first secretarial job, I wanted to be Julia Redfern. We shared a burning desire to be writers. I envied Julia her big wooden desk with locking drawers, and the project she was working on. I’d been writing since I was seven, yet I never thought to keep a Book of Strangenesses:

“[She] turned to her lists of most beautiful and most detested words. Under the beautiful words, which began with ‘Mediterranean’ and ‘quiver’ and ‘undulating’ and ‘empyrean,’ she added ‘mellifluous.’ She added ‘intestines’ to her list of most detested words: ‘rutabaga,’ ‘larva,’ ‘mucous,’ and ‘okra.’”

My edition of A Room Made of Windows is a Yearling paperback, price $1.25. Inside, on the double-spread title page with Hyman’s pen and ink drawing of an old house and a huge tree and an overgrown garden and two figures — a young girl and an old woman — is this inscription: Warm greetings to Candice from Eleanor Cameron.

When Eleanor Cameron autographed my copy, I was already writing and publishing children’s books. Yet I felt like Julia Redfern, a young girl looking up to the older, more accomplished writer. Just now, when I opened my copy for the first time since Cameron signed it nearly thirty years ago, I realized that I’m the older woman in Hyman’s drawing.