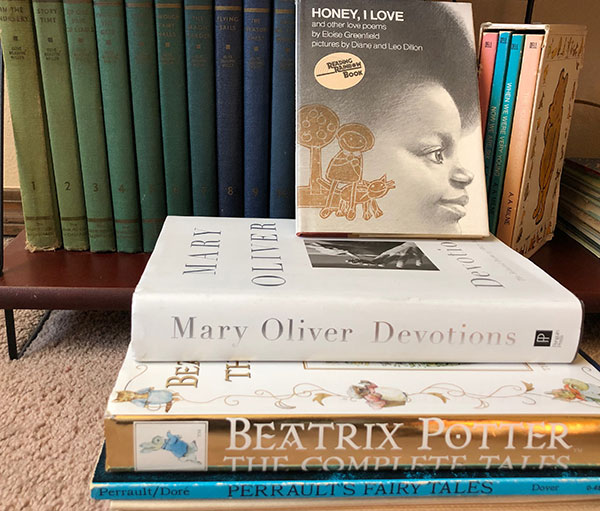

In the beginning, before I found myself within the pages of a book identifying with this character or that one, I listened to my grandmother read aloud from My Book House while surrounded by my eight siblings. The giant, multi-volume anthology contains poetry from Mother Goose to Shakespeare, selections from the Song of Solomon to Christina Rossetti to Robert Louis Stevenson, folk and fairy tales from around the world, Aesop’s fables, as well as some not-as-old previously published stories like The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter. In everything my grandmother read, what moved me beyond all else was rhythm, the musicality of language, and how word-music shaped and intensified meaning.

One sentence from The Tale of Peter Rabbit, a story that gave me endless nightmares, rings clear in my auditory imagination still, even though it has been decades since I’ve read it:

But round the end of a cucumber frame, whom should he meet but Mr. McGregor!

The near dactylic meter of the line sets my feet tapping. It’s a rolling rhythm, an invitation to dance. But the content, the words themselves, had my pulse racing in sheer terror. How can Peter possibly escape this surprising encounter with the giant, rake-wielding murderer — the very man who killed his father? The very man Peter’s mother had warned him against — when the word-music describing Peter’s predicament is so lovely?

I was inside the language and language was inside me.

In a lifetime of reading, few sentences have impressed me more than that one: lyric swing coupled with potential death. The story’s tension is contained within language itself.

I was not an avid reader as a child like so many writers, though my older siblings were. I had them as role models to come back to but, as a child, I was busy playing. Or babysitting. Or doing my various weekly chores. So when it came time to write and present book reports in school, I made them up. I hadn’t read a thing. My teachers had never heard of the books I wrote about and, always, my answer to their question was, “Oh, it’s a book my grandmother gave me.” I was a liar (a.k.a. storyteller) from a very early age.

Listening to Beatrix Potter began my love affair with musicality through animal fantasy, and A.A. Milne continued it. (Milne, another master of lyrical language). I read and reread the four books in their cardboard case dozens, if not hundreds, of times. No one character stood out for me, but being part of a family of eleven, plus numerous pets, I loved the sheer number of characters abiding in the Hundred-Acre-Wood and its surrounding Forest.

In addition to character-filled animal fantasies, I loved fairy tales and, there, I began identifying with the wretched, the humble, the poor. In elementary school, my friends and I complained at how utterly overburdened we were by our household chores. One day, when we (finally!) had a chance to play together, we started a Cinderella Club. My friend Shannan was appointed life-time president, as she had to dust mop her kitchen floor every morning before we walked to school. I had never heard of dust mopping. I was simultaneously fascinated and appalled.

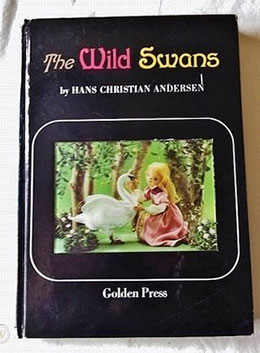

Another fairy tale I found myself in was Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans (Golden Press, 1966). It was not from the collection of tales that we had in the bookcase; I had my very own copy. And it had a hologram on the cardboard cover, something I’d never seen before. When I tilted it under the light, the picture changed before my eyes. And the illustrations inside were not line drawings or paintings in modest colors, they were full-color, vibrant three-dimensional scenes. Theatre enacted on the page. Enthralled, I began reading more.

Another fairy tale I found myself in was Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans (Golden Press, 1966). It was not from the collection of tales that we had in the bookcase; I had my very own copy. And it had a hologram on the cardboard cover, something I’d never seen before. When I tilted it under the light, the picture changed before my eyes. And the illustrations inside were not line drawings or paintings in modest colors, they were full-color, vibrant three-dimensional scenes. Theatre enacted on the page. Enthralled, I began reading more.

The story of the wild swans is the story of a girl, a princess, who saves her eleven brothers from the evil queen who had turned them into swans, by knitting sweaters from stinging nettles. I had five brothers, and thought that I, too, could save them all — though from what I wasn’t sure. I didn’t know how to knit, but I did know how to sew, and since I’d already identified with the hard-working Cinderella, surely I could make a coat or some other article of clothing to save everyone I loved.

Perhaps, because I was so steeped in folklore, I went through a rather long spell reading historical fiction— but not ordinary historical fiction — it had to be time-slip fantasy: The Children of Green Knowe by Lucy Boston, Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce, and later, during my near 20-year stint as a librarian, The Time Traveler’s Wife by Audrey Niffenegger. I never enjoyed history or social studies as a subject in school, but I devoured historical fantasy and wanted to be the time travelers, wherever they went.

And finally, returning to musical language, I have on my shelf an autographed copy of Honey, I Love by Eloise Greenfield and Devotion by Mary Oliver, among several others by Ms. Oliver. In my early twenties, I was student-teaching in a fourth-grade class and the poem, “Honey, I Love,” appeared in the reading textbook that the school used. My heart stopped when I read it. I immediately went to the library to see if Ms. Greenfield, whom I would meet years later, had written any whole books of poetry. The cadence of Greenfield’s poems had the same patterns as my grandmother’s speech. You could sway to the rhythm, the same way you can sway to the sounds of Beatrix Potter and A. A. Milne. I found my home in poetry, and begin every day reading poems, always beginning and ending with one by Mary Oliver, a poet whose work I’ve long admired for its lyricism, its mystery, and its sheer beauty.

My mother had a My Book House set and my father had a set of The Children’s Hour — we called them “the red books” — and we read them both to smithereens. I have since gotten replacement sets at antique stores and secondhand book shops. They even smell the same!

I replaced our set too– I know! I love their aroma. 🙂

A wonderful post! I now have more insight into your own lovely, lyrical writing, Cynthia. Have always admired your books for their masterful use of language. Happy writing!!

Thank you, Jen! Happy writing to you, too. Be well!