The notion of a “do-over” is alive and well on school playgrounds across the country. Ask any recess supervisor and they will confirm this. You hear it being requested on four-square courts, under basketball hoops, and on football fields… “Awwww, that should be a do-over!” Kids know that sometimes you just need another chance to get it right.

As an educator with nearly three decades of teaching experience, one might think that by this point in my career, my wish-list for “do-overs” in the classroom would be getting smaller and smaller. Yet, the truth is, it’s the exact opposite. That list of teaching regrets, what I wish I could “do over,” continues to grow. You see, as I become older and wiser, I realize more than ever the importance of reflection. Whether I am pondering the effectiveness of my lessons, examining formal or informal data, or speculating on my ability to be proactive versus reactive, I find myself feeling like a 4th grader on the playground, pleading for a chance to do it over.

This school year I’ve been given an incredible opportunity to raise my racial consciousness and learn what it means to become an interrupter of racial inequality. My school district invests heavily in promoting this unique and very necessary form of professional development. (See more information below.)

As part of my racial equity journey, I am writing my “racial autobiography.” The ultimate goal for composing this personal narrative centered on race is to disrupt the current state of affairs by eliminating the racial predictability of the achievement gap. My personal goal in writing a racial autobiography is to positively impact how I approach my role as a culturally responsive educator. Within this program, I’ve discovered that creating and sharing personal racial identities is an effective way for educators to promote a greater understanding of our collective racial experiences. It provides a chance for us to engage in courageous conversations centered on race.

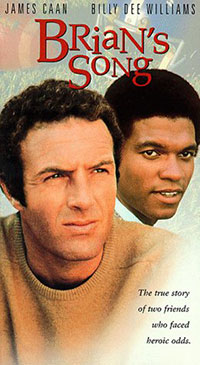

In writing about my life in terms of race, I’ve discovered that until my senior year of high school, the interactions I had with people of color were only through books and movies. Growing up in Dubuque, Iowa, it wasn’t until I plopped down in front of the TV in November 1971, for the ABC Movie of the Week, that I met a black person for the very first time. I was eight years old when I watched the tear-jerker about cancer-stricken Brian Piccolo and his teammate, Gale Sayers. Brian’s Song depicts the experiences of two Chicago Bears football players who became the first racially integrated roommates in the NFL. Sitting next to my older brother who just wanted to watch a football movie about his favorite team, the story captured my attention for very different reasons. I was full of questions as my racial consciousness was stirred. My childhood naiveté about race left me wondering why it was such a big deal for a white man and a black man, players on the same team, to share a room. I was curious and confused. After the movie ended, I could not stop thinking about the friendship between the two men.

In writing about my life in terms of race, I’ve discovered that until my senior year of high school, the interactions I had with people of color were only through books and movies. Growing up in Dubuque, Iowa, it wasn’t until I plopped down in front of the TV in November 1971, for the ABC Movie of the Week, that I met a black person for the very first time. I was eight years old when I watched the tear-jerker about cancer-stricken Brian Piccolo and his teammate, Gale Sayers. Brian’s Song depicts the experiences of two Chicago Bears football players who became the first racially integrated roommates in the NFL. Sitting next to my older brother who just wanted to watch a football movie about his favorite team, the story captured my attention for very different reasons. I was full of questions as my racial consciousness was stirred. My childhood naiveté about race left me wondering why it was such a big deal for a white man and a black man, players on the same team, to share a room. I was curious and confused. After the movie ended, I could not stop thinking about the friendship between the two men.

The story of Piccolo and Sayers stayed with me. What for some was an ordinary weekly TV-watching experience, this movie remains one of the most vivid memories from my childhood. I recall going to the public library five years later as a junior high student to check out the book I Am Third by Gale Sayers. As a teenager I had begun hearing about and witnessing more examples of bigotry and stereotypes, racism, in subtle and not so subtle ways. I wanted to get to know this man of color who I had encountered years earlier. It wasn’t until just a few months ago that the significance of that Tuesday evening in 1971 would be fully understood. In writing my racial autobiography, I discovered that this initial exposure to people who were intent on interrupting racial injustice contributed in profound ways to my racial consciousness.

So what does wanting a “do-over” have to do with my racial autobiography? My desire to have another chance stems from the realization that, as an educator, I missed out on far too many opportunities to create critical literary experiences, as well as lived ones, that were focused on racial awareness and racial equity. The idea of teaching about “white privilege” in an explicit way was barely on my radar. My classroom was filled with mostly white students for years, yet I did little to help those kids learn about and appreciate others who not only looked different but experienced life in a much different way. Yes, there were stories about Martin Luther King, Jr., Ruby Bridges, and Rosa Parks and there were lots of books brought out for Black History Month. However, now I see that those minimal efforts actually may have done more harm than good. By isolating the teaching and learning about people of color to just a few individuals and one month out of the entire school year, what message was I sending to kids?

If I had to do it all over again, I would be intentional in my teaching about race, racism, and white privilege. In a classroom full of six-year-olds, I would seize opportunities to talk with kids about these issues. I would devote time to helping my students gain an appreciation for racial equity by exploring the need to embrace diversity in people, thoughts, and approaches to problem-solving. We would learn about how talking about race and working towards social justice benefits everyone. As former Spelman College President Beverly Daniel Tatum puts it, “It’s not just understanding somebody’s heroes and holidays.”

As a white, female educator, I represent the demographic of approximately 75% of public school teachers in this country. Since do-overs are much easier to come by on the school playground than they are in our classrooms, I invite all who read this essay to join me in my effort to get it right from here on out. Let’s embrace the opportunity for learning and teaching about racial awareness in order to address the urgent need for racial equity in today’s world.

Resources

I offer this list of resources to help you with your racial equity teaching and learning journey:

What I’m reading with kids

What I’m reading with kids

A is for Activist by Innosanto Nagaro

Heart and Soul: The Story of America and African Americans by Kadir Nelson

Ghost by Jason Reynolds

Be a Changemaker: How to Start Something That Matters by Laurie Ann Thompson

What I’m reading for personal and professional development

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson

Waking Up White and Finding Myself in the Story of Race by Debby Irving

The mission: Putting more books featuring diverse characters into the hands of all children. Visit We Need Diverse Books.

The vision: A world in which all children can see themselves in the pages of a book.

More information about Glenn Singleton and Courageous Conversations.

To learn more about writing your racial autobiography, check out this link.

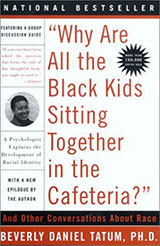

Author of the book, Why Are All The Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? Beverly Daniel Tatum offers insights on color blindness, racial stereotypes, and the media in this PBS interview.

Author of the book, Why Are All The Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? Beverly Daniel Tatum offers insights on color blindness, racial stereotypes, and the media in this PBS interview.

“60+ Resources for Talking to Kids About Racism” by Lorien Van Ness, provides a lists of books and activities to help adults begin the dialogue, starting with birth to three-year-olds.

An extensive list compiled by The Washington Post, offering articles, resources, and research, “Teaching about race, racism and police violence: Resources for educators and parents.”

More about the St. Louis Park (Minnesota) Equity Coaching Program

Every educator in St. Louis Park schools works one-on-one with an Equity Coach, who offers support, resources, and training in a number of ways. Through conversations, workshops, observations and coaching, teachers learn about the importance of raising their racial consciousness in an effort to disrupt systemic racism.

In September, 2013, the St. Louis Park School District started a program called Equity Coaching to help address the achievement gap and to improve educational equality in its schools. Grant funds from the state-sponsored Quality Compensation (Q Comp) grant (also known as ATPPS; Alternative Teacher Professional Pay System) help fund the Equity Coach initiative.

The Equity Coaching blog further describes the St. Louis Park Schools Equity Coaching Model: “Systemic racial equity change transpires when educators are given the space and support to critically reflect on their own racial consciousness and practice. Equity coaching provides sustained dialogue in a trusting environment to interrupt the presence of racism and whiteness. Using Courageous Conversations Protocol, tenets of Critical Race Theory, and instructional coaching methods, educators, and coaches engage in this.”