This month we have been thinking about the mysteries of the visual arts — how some artists must create, no matter the circumstances. Some do it with love and encouragement, some do it alone in an abandoned chicken coop, or in a slave’s work shed. But we are all richer for this art and we want to celebrate these creators.

Judith Scott was a twin. Her sister Joyce (along with Brie Spangler and Melissa Sweet) tell the story of her life in Unbound The Life and Art of Judith Scott (Alfred A. Knopf, 2021). Judith and Joyce were always together as children…”we are each other’s world. We share everything — our mom, our dad, our three older brothers, and our home. Together, under the sun, the moon, and the stars, it’s all we know, and we are happy.”

Judith Scott was a twin. Her sister Joyce (along with Brie Spangler and Melissa Sweet) tell the story of her life in Unbound The Life and Art of Judith Scott (Alfred A. Knopf, 2021). Judith and Joyce were always together as children…”we are each other’s world. We share everything — our mom, our dad, our three older brothers, and our home. Together, under the sun, the moon, and the stars, it’s all we know, and we are happy.”

But when it comes time to go to school, Joyce gets on the bus but Judy must stay home. She has Down Syndrome and in her school days (the 1940s) there was no place for her in the classroom. “The doctors say she is slow and will not get better, but they don’t know Judy like I do. She is perfect just the way she is. She knows things that no one else knows and sees the world in ways that I never will.” Judy is sent off to an institution. Joyce is heartbroken. “…my whole world disappears and is replaced with the colors of gone.” Joyce can hardly bear to visit the dreary institution.

And when she becomes an adult she makes arrangements for Judy to live with her in California. She enrolls Judy in the Creative Growth Art Center. “Many months go by, but nothing interests her, Judy only wants to look at her magazines.” Then one day the teacher puts out twigs, yarn, wood, and pins. Judy starts to create, wrapping and tying objects into a shape. And the next day she makes another, and another. “For years Judy wraps and weaves, creating fantastic, cocoon-like shapes filled with color.” A timeline tells us that Judy’s art was first shown in 1999. She died of heart failure in 2005. Now her art is known world-wide.

Unbound is the story of art released by love. Judy’s sister Joyce loved her so much she asked her to come and live with her, made it possible for her to go to an art workshop program where she began to make fiber art. As Joyce said, Judy “found a voice and a song all her own.”

James Castle’s story, as imagined and told by Allen Say in Silent Days, Silent Dreams (Arthur A. Levine, 2017) is the story of art that cannot be held back. In Say’s imagined life, (Castle’s family has disputed the details of this book) Castle made art with little encouragement in spite of multiple instances of his work being trashed, tossed, and left behind. James Castle made art — even when he only had soot, spit, and second-hand paper for materials. James Castle was born in 1899, mute, deaf, and autistic. “Anything that moved seemed to scare him…he could not hear himself shrieking.” His parents’ living room was the local post office. James played with magazines, folders, and extra paper. As a child he discovered pencils and began to draw. When he shrieked his father locked him in the attic. Left alone, he drew and hid his drawings in cracks in the walls.

James Castle’s story, as imagined and told by Allen Say in Silent Days, Silent Dreams (Arthur A. Levine, 2017) is the story of art that cannot be held back. In Say’s imagined life, (Castle’s family has disputed the details of this book) Castle made art with little encouragement in spite of multiple instances of his work being trashed, tossed, and left behind. James Castle made art — even when he only had soot, spit, and second-hand paper for materials. James Castle was born in 1899, mute, deaf, and autistic. “Anything that moved seemed to scare him…he could not hear himself shrieking.” His parents’ living room was the local post office. James played with magazines, folders, and extra paper. As a child he discovered pencils and began to draw. When he shrieked his father locked him in the attic. Left alone, he drew and hid his drawings in cracks in the walls.

At school kids pointed and laughed. James had no friends. He made paper dolls and animals out of junk paper and scraps and filled his room with his creations.

At age 10 James was sent to a school for the blind and deaf 160 miles from his home. He was fascinated by the school library and loved looking at the books, though he could not read. He loved watching teachers sew the books. Art was only taught to girls. When the teachers saw James drawing they took away all his art materials. He ran away. As punishment they made him copy the alphabet endless times. But he seemed to love the punishment! And made his own books using some real and some invented letters. At 15 he was sent home, called “incapable of learning.” And the principal warned his father not to let him draw.

The obstacles that James encountered in his world, perhaps lacking in love or attentiveness, even minimal friendship, are heart-breaking. Each time his family moved James’s art was left behind. When he moved into his next to last space — an old chicken coop in a sister’s yard — neighbor kids broke in and trashed his art. He once threw some of his work into a stream. Perhaps he wanted to be the one to let it go.

But he continued to make art and animals for 30 years in his chicken coop home and studio. A nephew was the only person he invited in. And when his nephew went to art school he showed one of his professors some of Uncle Jimmy’s drawings. That was the end of obscurity for James Castle. A show of his work was eventually organized in Boise. James attended in a silk suit. A sister, not wanting others to see the chicken coop, eventually bought him a trailer to live in. For 15 years he had his own house, where he continued to make art.

Allen Say has illustrated this remarkable book using the materials that James Castle might have used — a lot of soot and spit, shoe polish, laundry bluing. Say and his wife recreated Castle’s art meticulously, respectfully, artistically. The mostly monochromatic drawings are punctuated by a rainbow painted onto the roof of the gallery where James’s show was hung. In a YouTube video Say admits that James Castle wouldn’t have drawn the rainbow but the fellow artist, Say, gave it to him — a gift from an admirer. James Castle had to draw and construct his own world of friends. He never knew Allen Say or any of the rest of us who are so moved by his passion and his work.

Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave (Little Brown, 2010) by Laban Carrick Hill and illustrated by Bryan Collier is the story of a slave in South Carolina who learned to make pots — huge pots, pots that held 25 – 40 gallons. And what’s more, in a time when it was illegal for slaves to read and write, Dave wrote on some of his pots: “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all and every nation. Dave August 16, 1857.”

Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave (Little Brown, 2010) by Laban Carrick Hill and illustrated by Bryan Collier is the story of a slave in South Carolina who learned to make pots — huge pots, pots that held 25 – 40 gallons. And what’s more, in a time when it was illegal for slaves to read and write, Dave wrote on some of his pots: “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all and every nation. Dave August 16, 1857.”

The book begins with Dave’s vision, “To us it’s just dirt… / But for Dave/it was clay, / the plain and basic stuff/upon which he learned to / form a life / as a slave nearly / two hundred years ago.”

Hill repeats this pattern later in the story: “To us it is just a pot, / round and tall / good for keeping / marbles / or fresh cut flowers. / But to Dave/it was a pot / large enough to store / a season’s grain harvest / to put up salted meat / to hold memories.”

Hill and Collier bring Dave to life for readers with details like his thumbs, chapped from working with clay, with quotes from Dave’s pots. In a YouTube video, Collier tells students, “he [Dave] was talking to the future.” Collier tells the students Dave made over 40,000 pots in his lifetime. Now his pots sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars each.

But it’s not the money that impresses, it’s the vision of this man, a slave, who never left South Carolina, who made pots so big they seem to defy gravity and wrote his name on them so all would know — for all time — who made them. Art will out.

Alma Thomas is not an outsider artist in the same way as Judith Scott or James Castle, but she is an artist who broke barriers, and we want to celebrate her story, both for her own brilliant paintings and for what she gave to children. Ablaze With Color, A Story of Painter Alma Thomas, (Harper 2022) by Jeanne Walker Harvey and illustrated by Loveis Wise, whose vivid colors carry us from spread to spread, welcomes us into Alma Thomas’s life and art. As a child Alma loved being outside among “pastel purple violets and crimson roses crowned by bright green banana leaves.” From little on, she made things, not by sewing or cooking as her sisters did, but by shaping stream clay into bowls and cups and drying them in the sun.

Alma Thomas is not an outsider artist in the same way as Judith Scott or James Castle, but she is an artist who broke barriers, and we want to celebrate her story, both for her own brilliant paintings and for what she gave to children. Ablaze With Color, A Story of Painter Alma Thomas, (Harper 2022) by Jeanne Walker Harvey and illustrated by Loveis Wise, whose vivid colors carry us from spread to spread, welcomes us into Alma Thomas’s life and art. As a child Alma loved being outside among “pastel purple violets and crimson roses crowned by bright green banana leaves.” From little on, she made things, not by sewing or cooking as her sisters did, but by shaping stream clay into bowls and cups and drying them in the sun.

As Black people living in Georgia in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Alma and her sisters couldn’t visit museums or libraries or attend the next-door school, so their parents filled their lives with books and teachers who were invited into their home to talk about people and places beyond Georgia. When the family moved to Washington, D. C., Alma was able to attend college and study art. After graduation she taught in the local segregated school. Even though she still painted, Alma devoted herself to introducing countless students to art in any way she could, including having them make marionettes and put on puppet shows in Alma’s home. She led field trips, organized art clubs, and set up an art gallery in a school.

When at age seventy Alma stopped teaching and turned again to her own art, she still painted colors but in a new way: “Circles and stripes. Dashes and dabs. Ablaze with color. Soft colors bright colors…She painted how she felt on the inside when she experienced nature outside…. How nature made her heart sing and dance, even when life could be hard and unjust.” Space travel inspired more paintings.

Then, Harvey tells us, “the unexpected happened.”

The Whitney, a famous New York art museum, featured Alma’s ‘12 Paintings of Earth and Space in the first solo show by a Black woman. The Corcoran Gallery of Art in D.C. also showed Alma’s paintings, and the mayor of Washington, D.C., honored Alma’s work with children by naming September 9 Alma Thomas Day. Yet another honor came years after Alma had died when Barack and Michelle Obama chose Alma’s painting Resurrection to hang in the White House, the first artwork by a Black woman to be displayed there, “a painting of hope and joy. Ablaze with glorious color. Alma’s colors.”

“Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man,” Alma Thomas said. Her colorful paintings expressed her belief that “colors are the children of light… that reveals the spirit and living soul of the world.” Alma’s spirit, like her art, brightens our world’s living soul.

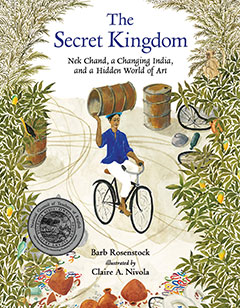

Like James Castle, Nek Chand made art with what he found — and he made his “outsider” art outside. In The Secret Kingdom: Nek Chand, a Changing India, and a Hidden World of Art (Candlewick Press, 2018) by Barbara Rosenstock with illustrations by Claire A. Nivola, we learn about Nek’s childhood in the Punjab region of colonial India. “In the tiny village, Nek played and planted, laughed and listened, as the stories circled with the seasons, beginning to end and back again.” While they farmed, Nek’s father told stories of wise kings. His mother told of graceful goddesses. During the monsoon season his sisters told of magical geese, and while the family harvested kanak Nek’s brothers told stories of fierce jackals and chattering monkeys. His head overflowing with stories, Nek made his own world on the banks of the village stream out of silt and clay and sticks and rocks.

Like James Castle, Nek Chand made art with what he found — and he made his “outsider” art outside. In The Secret Kingdom: Nek Chand, a Changing India, and a Hidden World of Art (Candlewick Press, 2018) by Barbara Rosenstock with illustrations by Claire A. Nivola, we learn about Nek’s childhood in the Punjab region of colonial India. “In the tiny village, Nek played and planted, laughed and listened, as the stories circled with the seasons, beginning to end and back again.” While they farmed, Nek’s father told stories of wise kings. His mother told of graceful goddesses. During the monsoon season his sisters told of magical geese, and while the family harvested kanak Nek’s brothers told stories of fierce jackals and chattering monkeys. His head overflowing with stories, Nek made his own world on the banks of the village stream out of silt and clay and sticks and rocks.

When Nek was grown, “the men with the guns came,” and colonial India was partitioned into two countries, Pakistan and India, based on religion. Because Nek’s family was Hindu living in now-Muslim Pakistan, they had to leave their homeland. “Nek carried only village stories in his broken heart.”

In Chandigarh, a “sharp-edged city of colorless concrete” built on land where twenty-six villages had been bulldozed to make way for the new city, Nek found work as a government road inspector. But he wondered, “Where were the curving paths and flowing streams? Where were the singing men, the swaying women? Where were the stories?” When he discovered acres of unoccupied scrubland on the city’s edge, Nek began transforming the hidden wilderness. He cleared land, built a mud hut, and began to gather up bits and broken pieces of discarded trash along the roads. He carried them to his hidden wilderness and in time he began to build his secret kingdom with concrete and shards of cracked sinks and pots and broken glass bangles. He replanted and tended half-dead plants from the city dump. He covered frames of twisted bikes and rusty pipes with concrete, “sculpted packs of jackals, troops of monkeys, and flocks of geese. Beginning to end and back again, Nek found each group a place to belong, until he belonged too — king of a hidden land of stories.”

For fifteen years his kingdom stayed secret, but when a government crew clearing land discovered his illegal building and reported him, officials decided to clear his land.

“Until the people of Chandigarh came.”

They came to see this magical world, gave money and tools to help save it, collected scraps to recycle, and convinced government officials to let Nek Chand stay “in the place he belonged.” Now people from all over the world visit Nek Chand’s no-longer-secret kingdom to marvel at the creation he never stopped building, a place that “tells the stories people need to hear…stories of coming home. “

A double gate fold spread reveals photos of Nek Chand’s secret kingdom, and back matter tells us more about how, with nothing more than cast-off materials, his memories and stories, and a longing for home Nek Chand created a gift of art and yearning for us all.

In an interview Rosenstock told how she was seized by the idea of writing about Nek Chand while working on another picture book biography that at the time “was going nowhere. I was bored. I was frustrated… I sat in my office searching random things on my laptop, and accidentally googled something like, ‘artists working outside’. Boom! There was a picture of a waterfall with oddly cool statues in front of it….” Captivated by Nek Chand’s art, Rosenstock temporarily set aside the book she was working on to write Chand’s story. Books, Rosenstock tells us, are born of passion.

And so is art, no matter where we find it. We expect to find art in some locations: museums, art schools, public squares, sides of buildings. But some art takes us by surprise, unexpected art, often by unexpected artists.

Why they should be unexpected we don’t know — shouldn’t we expect to find beauty anywhere and everywhere? One more gift of outsider artists is how they reveal the creative spirit that lives in us all.

Art will out.

more …

The Secret Kingdom: Nek Chand, a Changing India, and a Hidden World of Art was reviewed in Bookology, February 1, 2018.

Read more of Barb Rosenstock’s interview about The Secret Kingdom at Unleashing Readers.