by Jacqueline Briggs Martin and Phyllis Root

As we have talked about doing this column we have realized that we can only call this an introduction to the work of Ashley Bryan. His life has been so full of making children’s books and there are so many wonderful children’s books that we can only call out a few — a few enticements, and encourage you to take yourself on a wonderful journey into Ashley Bryan’s world.

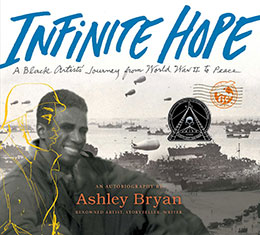

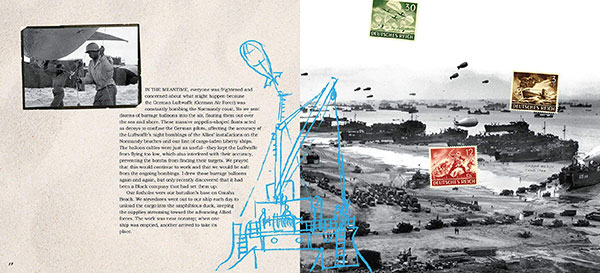

Infinite Hope is an unforgettable book. It contains several strands of information: Ashley Bryan’s drawings and paintings done from those drawings from his time as a soldier, drafted into World War II; his letters to Eva; photographs as background information, illustrating places he encountered or was stationed; text written recently recollecting Bryan’s wartime experiences. These strands give readers a powerful and textured sense of Bryan’s wartime experience. He dispassionately describes the many instances of racism the about 20 members of the 502 Battalion encountered: while stationed in Belgium they quickly made friends with the Belgians, were invited into their homes and shared good times. To put an end to this socializing the white officers prohibited the Black soldiers from leaving the base on weekends, though no such prohibition was laid on the whites; the Black officers were not allowed in the officer’s facilities or clubs; on Omaha Beach during the D‑Day landing, the bodies of Black soldiers were quickly removed from the beach so they would not show up on newscasts; German prisoners of war (captured enemy soldiers!) were allowed to sit in the front of buses and socialize with whites; Blacks had to sit in the back; Blacks were the last to be sent home and could only be on board a ship if there were no whites to take those spots. One of the most chilling pictures is Black soldiers detailed to clear as-yet-unexploded mines, during which, Bryan tells us, many Black lives were lost.

Infinite Hope is an unforgettable book. It contains several strands of information: Ashley Bryan’s drawings and paintings done from those drawings from his time as a soldier, drafted into World War II; his letters to Eva; photographs as background information, illustrating places he encountered or was stationed; text written recently recollecting Bryan’s wartime experiences. These strands give readers a powerful and textured sense of Bryan’s wartime experience. He dispassionately describes the many instances of racism the about 20 members of the 502 Battalion encountered: while stationed in Belgium they quickly made friends with the Belgians, were invited into their homes and shared good times. To put an end to this socializing the white officers prohibited the Black soldiers from leaving the base on weekends, though no such prohibition was laid on the whites; the Black officers were not allowed in the officer’s facilities or clubs; on Omaha Beach during the D‑Day landing, the bodies of Black soldiers were quickly removed from the beach so they would not show up on newscasts; German prisoners of war (captured enemy soldiers!) were allowed to sit in the front of buses and socialize with whites; Blacks had to sit in the back; Blacks were the last to be sent home and could only be on board a ship if there were no whites to take those spots. One of the most chilling pictures is Black soldiers detailed to clear as-yet-unexploded mines, during which, Bryan tells us, many Black lives were lost.

published by Caitlyn Dlouhy Books / Atheneum Books / Simon & Schuster, 2020

The constant thud and pelt of racism is certainly a part of this book. But an even stronger part is Bryan’s survival strategy — his passion for drawing. While stationed in Boston, before being sent to Europe, he drew with the children in the neighborhood. He drew while operating a winch. “In my knapsack, in my gas mask, I kept paper, pens, and pencils. I would draw whenever there was free time, intervals in work. I refused to sleep. I had to draw. It was the only way to keep my humanity. My sketches weren’t only to record the day’s happenings, but also to level out the day, the experiences of the day, to find the humanity — that moment of grace when you transform experiences into something meaningful, something creative amidst the devastation around you, the ugliness of war….Thank goodness I never needed to use my gas mask — if I had had to pull it over my head in a hurry, a rain of paper and pencils would have tumbled down.” Art helped him survive.

Coming home, he put away his wartime sketches rather than painting from them as he had when serving in the army but continued with his art. “What I painted most steadily for the next several decades,” he writes, “were the flowers that brightened the gardens on Little Cranberry Island, my home.” Fifty years after the war, he was asked to do paintings based on those wartime sketches. Bryan writes that had he painted from the drawings immediately after the war, he would have painted in black, grays, dark colors. Years later, he saw the way the soldiers had created their own world to protect themselves from “all sorts of war” including racism and segregation even as they were fighting for freedom. “I can never give them more than they gave me,” he writes, “so I would paint them in full color, filled with the vibrancy and life I have put into my garden paintings.”

On page 19 of this memoir we read a note by him, “GOD, make me brave for life.” It is fair to say that God did just that. Ashley Bryan is brave in encountering life in all its injustice and complication and transforming what he encounters into art. He is passionate about his art and has been for all his life. He has illustrated his own books as well as the books of others. The woodcuts he created for Lorenz Graham’s How God Fix Jonah are so full of energy and emotion that it is tempting to “read” the book and not even look at the words. (The words are well worth reading, though, for the voice and musicality of the West African idiom with which Graham retold Biblical stories.)

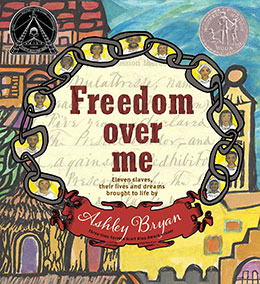

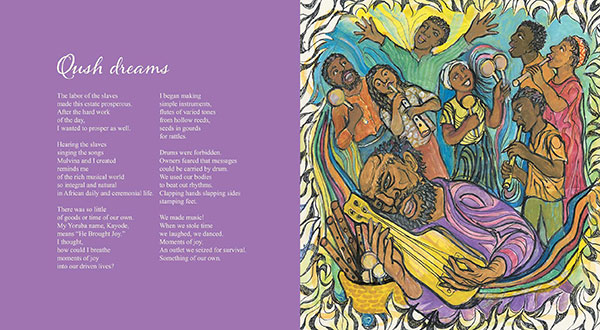

Freedom Over Me is Ashley Bryan’s reconstruction of the lives of eleven people whose names he found in a collection of slave-related documents. “Eleven slaves are listed for sale with the cows, hogs, cotton; only the names and prices of the slaves are noted (no age is indicated)….My art and writing in this story aim to bring the slaves alive as human beings.” And so he does, he invents their dreams, their losses. Peggy is the cook, brought from Africa, who feels close to the mother she was separated from on the auction block, when she steams roots and herbs. And Peggy’s strong, unflinching face looks carved from African wood. Stephen, a carpenter, who loves Jane, a seamstress, and build a special sewing shed for her. Jane: “The praise I receive, /I offer as a tribute/to my ancestors.”

Freedom Over Me is Ashley Bryan’s reconstruction of the lives of eleven people whose names he found in a collection of slave-related documents. “Eleven slaves are listed for sale with the cows, hogs, cotton; only the names and prices of the slaves are noted (no age is indicated)….My art and writing in this story aim to bring the slaves alive as human beings.” And so he does, he invents their dreams, their losses. Peggy is the cook, brought from Africa, who feels close to the mother she was separated from on the auction block, when she steams roots and herbs. And Peggy’s strong, unflinching face looks carved from African wood. Stephen, a carpenter, who loves Jane, a seamstress, and build a special sewing shed for her. Jane: “The praise I receive, /I offer as a tribute/to my ancestors.”

published by Caitlyn Dlouhy Books / Atheneum Books / Simon & Schuster, 2016

Reading this book makes one weep, both for the stories and also the dreams of people brutally enslaved, no matter how “kind” their masters and mistresses might be. As they tell their stories, they also tell their dreams of remembered family and life in Africa as well as their yearnings to be free. Sixteen-year-old John, being trained as a carpenter, loves drawing and draws in the mud with sticks as well as the used paper given him by Stephen and Jane, two enslaved people who look on John as their son. (In Infinite Hope, Bryan, desperate for paper to draw on in the aftermath of the war, resorts to using the flat squares of brown toilet paper the soldiers had been issued.)

This moving book makes clear what was lost, what was contained in the Appraisement list of names and dollars Bryan includes at the back of the book. Bryan honors these lives, imagined, remembered, dreamed.

Beautiful Blackbird is a beautiful book. The cut-paper artwork in vivid solid colors shows the birds of Africa a long time ago “in their clean, clear colors from head to tail.” Only Blackbird was black all over. When Ringdove asks all the birds who is the most beautiful of them all, the birds all agree that Blackbird is the most beautiful one.

Beautiful Blackbird is a beautiful book. The cut-paper artwork in vivid solid colors shows the birds of Africa a long time ago “in their clean, clear colors from head to tail.” Only Blackbird was black all over. When Ringdove asks all the birds who is the most beautiful of them all, the birds all agree that Blackbird is the most beautiful one.

When Ringdove asks for Blackbird to share some of his black, Blackbird replies, “color on the outside is not what’s on the inside,” but promises to share his black color with the other birds. Painting them with dots and arcs and stripes Blackbird uses all of his blackening on every bird. When all the birds have been decorated, they gather round blackbird and sing,

“Our colors sport a brand-new look,

A touch of black was all it took.

Oh beautiful black, uh-huh, uh-huh

Black is beautiful, UH-HUH!”

Beautiful Blackbird feels like a classic work of children’s literature. And so does Beat the Story-Drum, Pum-Pum. The title is no accident — rhythm is a part of every page of this book. Here’s an early part of the first story: ”Hen strut two steps, pecked at a bug. Frog bopped three hops, flicked his tongue at a fly. Strut two steps, peck at a bug. Bom three hops, flick at a fly. Hen flapped her wings and spun around. Frog slapped his legs and tapped the ground.” That rhythm is just so much fun to read. We know when there’s a hen involved there’s often work to be done — and the other creatures don’t want to do it. So we know the shape of this story. Bryan wants us to have some fun along the way. “Why the Bush Cow and Elephant Are Bad Friends” features two huge characters who cannot resist the urge to fight to prove which one is strongest. No fight ever proves anything. And perhaps the main character of the story is the comic monkey who talks in scat rhythms and, when he goes to tell the Head Chief the two enemies are fighting again forgets his message and eats bananas.

Beautiful Blackbird feels like a classic work of children’s literature. And so does Beat the Story-Drum, Pum-Pum. The title is no accident — rhythm is a part of every page of this book. Here’s an early part of the first story: ”Hen strut two steps, pecked at a bug. Frog bopped three hops, flicked his tongue at a fly. Strut two steps, peck at a bug. Bom three hops, flick at a fly. Hen flapped her wings and spun around. Frog slapped his legs and tapped the ground.” That rhythm is just so much fun to read. We know when there’s a hen involved there’s often work to be done — and the other creatures don’t want to do it. So we know the shape of this story. Bryan wants us to have some fun along the way. “Why the Bush Cow and Elephant Are Bad Friends” features two huge characters who cannot resist the urge to fight to prove which one is strongest. No fight ever proves anything. And perhaps the main character of the story is the comic monkey who talks in scat rhythms and, when he goes to tell the Head Chief the two enemies are fighting again forgets his message and eats bananas.

The stories are told with a “well, this happened” attitude. The characters bring about their own fates — the frog fails to see the hawk, the frog and snake — best friends for one day — learn to be suspicious of each other and never play together again but sit alone in the sun. The man who counts spoonfuls can’t keep a wife because he can’t resist counting the spoonfuls of food she doles out of the pot. And his wives won’t live with that. He ends up alone, counting grass.

Rhythm makes a big return in the last story — Raluvhimba, God of the Bavanda, created the animals (without tails) when he fell asleep in Cave Luvhimbi. But he made a mistake (“…and man hadn’t even been created yet”) he created flies. The animals demand tails to flick away the flies. Raluvhimba says, “Tell the animals I’ll come down to Mount Tsha-wa-dinda tomorrow and make tails for all of them.” Rabbit is lazy and doesn’t go so ends up with a little fluff of a tail. But really, this story is about sound about the fun of these repeated syllables. And if we remember to get into line when the tails are being given out, so much the better. In the meantime here’s to Raluvhimba, God of the Bavanda. Let’s hope we can gather with him on Mount Tsh-wa-dinda and celebrate tales and tails and the beauty of sound and creation.

In looking through Bryan’s published works we discovered one we didn’t know, Ashley Bryan’s ABC of African American Poetry. Rather than having each letter begin a poet’s name Bryan includes lines from poems that began with or included that letter. So the letter A showcases lines from James Weldon Johnson:

In looking through Bryan’s published works we discovered one we didn’t know, Ashley Bryan’s ABC of African American Poetry. Rather than having each letter begin a poet’s name Bryan includes lines from poems that began with or included that letter. So the letter A showcases lines from James Weldon Johnson:

And God stepped out on space

And he looked around and said:

I’m lonely—

I’ll make me a world.

We were delighted to find words by many of our favorite writers in the book — Lucille Clifton, Eloise Greenfield, Langston Hughes — along with new-to-us poets as well.

What a gorgeous and wonderful way to learn more about Black poets.

We could go on and on about the many books Ashley Bryan has written and illustrated, and we hope you will go on reading Bryan’s books and listening to him read and talk about his work in the links we’ve included.

Beautiful books by Ashley Bryan. UH-HUH!

For a treat, listen to Bryan read Beautiful Blackbird.

And hear him giving voice to the wonderful rhythms in “Hen and Frog.”

I just requested INFINITE HOPE from my library. Thank you for the recommendation!

I hope you love it as much as we do.

LOVELY shout-out to Mr. Bryan’s newest & so fabulous a wrap-up. Appreciations.

Jan Godown Annino / Bookseedstudio