We love writing this column and have been doing it since 2015. Typically we decide on a topic or subject and write about books we love within that range. This month we had planned to write about several books we love that have been banned, but we realized that along with giving you a list of banned books we really wanted to write about the current tsunami of book banning in our country.

All of us who love books have heard about book banning. We might have seen pictures of school libraries with empty shelves whose books are being “evaluated.” Perhaps we’ve dealt with banning in our local schools and libraries.

On the PEN America website we find this information about book banning: “Hyperbolic and misleading rhetoric about ‘porn in schools’ and ‘sexually explicit,’ ‘harmful,’ and ‘age inappropriate’ materials led to the removal of thousands of books covering a range of topics and themes for young audiences.

Overwhelmingly, book bans target books on race or racism or featuring characters of color, as well as books with LGBTQ+ characters. And this year, banned books also include books on physical abuse, health and well-being, and themes of grief and death. Notably, most instances of book bans affect young adult books, middle grade books, chapter books, or picture books — books specifically written and selected for younger audiences.” According to PEN America, in the 2021 – 22 school year 327 individual picture book titles were banned in the United States.

The PEN website also tells us: “In a May 2023 Ipsos/NPR poll, 65 percent of Americans stated that they oppose book bans by school boards, and 69 percent oppose book bans by state lawmakers.”

But book banning continues, and it affects us all — writers, who see their books removed from libraries, or more insidiously, just not ordered for libraries, teachers and librarians who can face wrathful parents who say they are worried about what their children may be reading.

New York Times best-selling author Eliot Schrefer experienced a firestorm of negative emails, tweets, and Facebook posts regarding his book Queer Ducks. The book, published in 2022, is illustrated non-fiction about homosexual behavior in the animal kingdom. It received five starred reviews, but Schrefer says that it was “underordered” by schools and libraries. Then it was named a Printz Honor book. Schrefer was interviewed on NPR, appeared on The Daily Show. People began to notice his book, people who don’t want kids to read about any kind of homosexual behavior. He was the target of many critical, de-humanizing comments and finally had to stop reading his own emails.

He says of the current wave of book challenging, “This is different from how banning worked before [when one parent might object to a particular book] …. Books are place holders for cultural arguments. [Some parents], foot soldiers really do believe in what they are doing but the higher ups believe creating an enemy is the best way to get votes.”

Eliot Schrefer’s experience reminds us of the various ways that we all can be affected by book challenges and book banning. First there is soft censorship. His book was just not ordered, even though it received five starred reviews. Under-ordering means books sit in warehouses and publishers are required to pay taxes on those books. When publishers lose money on a book they are less likely to publish another book on that topic. So writers are limited in what they can write. Readers are limited in what they can read.

For statistics about who’s doing the challenging and the types of books being challenged, please read “Objection to sexual, LGBTQ content propels spike in book challenges,” by Hannah Natanson for The Washington Post, updated 9 June 2023. (Our thanks to Tasslyn Magnusson for her research in finding this article.)

Actual removal of books from libraries went up 33% from 2022 to 2023, according to PEN. What happens to kids’ who need to see themselves in books when they do not find those books? What happens to all our kids when they cannot read the real truths about our history? When they cannot read Before She Was Harriet by Lesa Cline-Ransome or Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre by Carole Boston Weatherford or Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation by Duncan Tonatiuh?

Children are denied access to our history and they are also denied stories. In J.J. Austrian’s book Worm Loves Worm two worms (who are, after all, hermaphroditic) want to get married. Yet the book has been banned, and one book banner has called Austrian a mind rapist. When J.J. reads the book to school children and asks them what the story is about, they respond that it’s about bullying, about the other insects trying to boss the worms around. Elana K. Arnold’s book What Riley Wore has also been banned. “It’s just a book about dressing for the occasion and wearing what feels good,” Arnold says, “and has no pronouns at all attributed to Riley.”

Red, A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall is a story about a blue crayon mislabeled as red who discovers he is really blue — and very good at being blue. Hall says the book is about the “unbridled joy of finding a place for one’s true self in the world.” He wonders if the people keeping Red out of schools would feel differently if they could see the messages of gratitude he’s received from parents and from others who struggle to be their true selves regardless of labels.

Michael Hall shares his experience with Red: A Crayon’s Story:

In Red, a story about a blue crayon mistakenly labeled as red, I wanted to convey the deep despair an individual must endure under the relentless pressure to conform to their community’s expectations and the unbridled joy of finding a place for one’s true self in the world. Early on, it was clearly going to be a story about gender nonconformity, but I wanted it to be relevant to many different ways people feel mislabeled. Eventually, I saw my own struggle with dyslexia in Red’s predicament.

A few years ago, a kindergarten school teacher in California read the book to her class at the request of her transgender student. This caught the attention of book banners who challenged it. Ideally, school is a place for children to meet people who are different from themselves. It’s an opportunity to learn and practice empathy. But hiding the very idea of gender nonconformity fosters bigotry and stymies students’ emotional development.

In the book, Red’s teacher, parents, and friends believe they are looking out for Red’s best interests as they try to help him do a better job of being red. Similarly, I like to think that most of those trying to keep Red out of schools do so without malice. And I wonder if they would be swayed if they were to see some of the notes I’ve received from parents, both liberal and conservative, who had the courage to help their trans children express their true selves; transitioning adults who use Red to explain what they’re going through; and trans grown-ups, who wish the book was available when they were younger.

At the end of the story, as Red discovers that he’s not red after all, all the other crayons celebrate. This might be pollyannaish, but I continue to believe that the virtues of acceptance and inclusion will triumph in the end.

How do these authors respond to being banned? J.J. Austrian believes that books need to give kids hope in the world. Elana K. Arnold in a published article said that having books banned reminds her that “it’s my great privilege to have a voice, and they spur me to be even louder.” Michael Hall believes that “acceptance and inclusion will triumph in the end.”

In an interview, Jason Reynolds, some of whose books have suffered banning, asked the core question, “What are they [book banners] afraid of?”

Book banners are afraid of the power of words and of stories and of books. The power of the imagination and of knowledge. The power of seeing ourselves portrayed in stories and books, of knowing that we, too, are part of the endless and wondrous ways of being in the world.

We also believe some in the book banning camp have a corrosive goal of weakening our faith in our public schools, weakening our confidence in the professional librarians and teachers who choose the books in our libraries and classrooms. When people lose faith in their institutions they are more vulnerable to lies and propaganda.

We want to share with you more titles of frequently banned books. You may see some of your favorites on the list. We always do.

- Sing a Song: How Lift Every Voice and Sing Inspired Generations by Kelly Starling Lyons

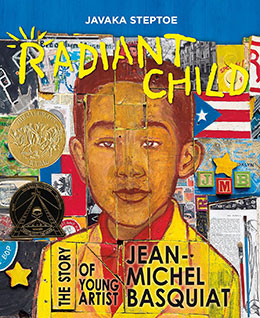

- Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat by Javaka Steptoe

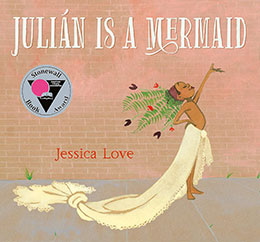

- Julián is a Mermaid by Jessica Love

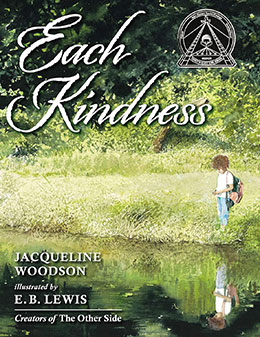

- Each Kindness by Jacqueline Woodson

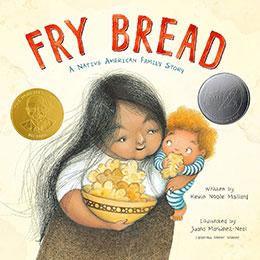

- Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story by Kevin Noble Maillard

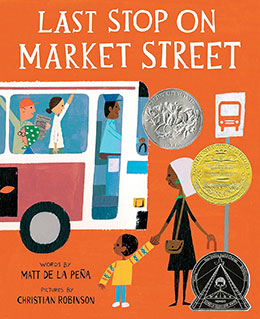

- Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña

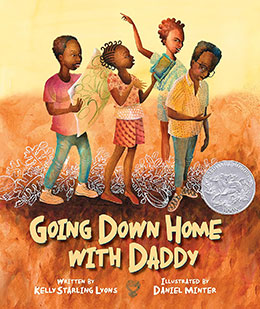

- Going Down Home with Daddy by Kelly Starling Lyons

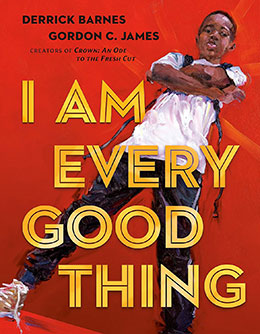

- I Am Every Good Thing by Derrick Barnes

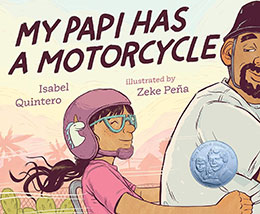

- My Papi Has a Motorcycle by Isabel Quintero

What can we do to resist this wave of book-banning?

- We can vote. We can elect to our schoolboards and our state legislatures candidates who believe that teachers and librarians have the knowledge and commitment to make good choices about the books in their classrooms and libraries.

- We can vote with our pocketbooks and buy banned books and make them available to readers – have them in our homes, give them to schools and libraries, leave them in little free libraries

- We can attend school board meetings and speak up about the books we love, the books we want to be available to all readers, even before there is an incident regarding our schools’ collections.

- We can write letters to the editors of our local and state newspapers about the importance of diversity in literature.

- We can support writers whose books are banned, whether online or directly if we have the chance. In the midst of an avalanche of attacks on Facebook, Eliot Schrefer especially remembers the supporter who fought back by writing, “My son read this book and now he’s a duck.”

When Eliot Schrefer was asked if the social media attacks against him for Queer Ducks had made him consider silencing himself, he replied “It made me want to raise my voice louder.”

All of us who love books and stories can raise our voices louder, too. Let’s all find the work we can do. We are stronger together.

What a fabulous essay! Thanks for both the fine argument AND for the book titles that I’ve missed along the way. As someone who has a novel(Twelve Days in August) on the infamous Texas list of “dangerous books”, I am passionate about this issue – not because of my book, but because of readers who might find themselves in the story, if they only had the chance to read it.

That’s the insidious part of these bans, that people aren’t being allowed to see themselves in books and as important members of our community.

Thank you! And I just found some new books to request at the library.

Thank you for this important essay! Its significance is loud and clear!