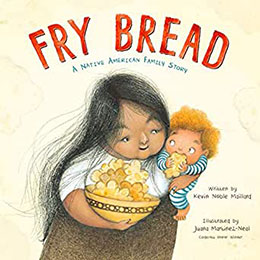

We have to confess to book envy — that is encountering a picture book and wishing that we had written it. The book’s approach is so arresting, the heart of the book so big, the images so rich. Such books not only make us wish we’d done them, they change what we want to do and what we can do. We always learn from them. Fry Bread could be one of those books — the heart is so big, the language so beautiful, the subject so encompassing — but we never could have written this book. It had to be written by Kevin Noble Maillard, a member of the Seminole Nation, Mekusukey band.

We have to confess to book envy — that is encountering a picture book and wishing that we had written it. The book’s approach is so arresting, the heart of the book so big, the images so rich. Such books not only make us wish we’d done them, they change what we want to do and what we can do. We always learn from them. Fry Bread could be one of those books — the heart is so big, the language so beautiful, the subject so encompassing — but we never could have written this book. It had to be written by Kevin Noble Maillard, a member of the Seminole Nation, Mekusukey band.

In this simple book about one food — fry bread — Maillard delivers a complex and beautiful paean to the Indigenous People of the United States. Begin with the end pages, filled with the names of Indigenous tribes. The illustrator, Juana Martinez-Neal has said that she imagines families of readers poring over the end pages looking for their own particular tribe.

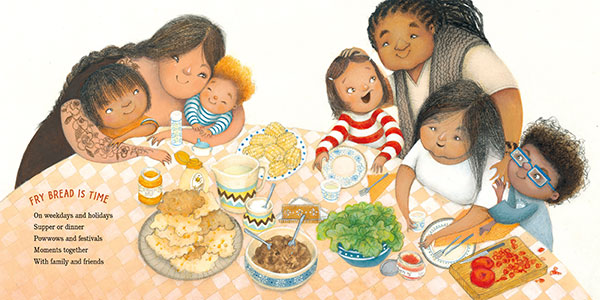

The poem to fry bread starts with senses: ”Fry bread is food/Flour, salt, water/Cornmeal, baking powder/Perhaps milk, maybe sugar/All mixed together in a big bowl.” “FRY BREAD IS SHAPE,” “FRY BREAD IS SOUND/ The skillet clangs on the stove/…Drop the dough in the skillet/The bubbles sizzle and pop.”/FRY BREAD IS COLOR,” “FRY BREAD IS FLAVOR.” Each page gives us another characteristic of fry bread — time (holidays, family celebrations); art (sculpture, landscape); history (“The long walk, the stolen land/Strangers in our own world/With unknown food/We made new recipes/From what we had/”) and more. One of our favorite spreads is “FRY BREAD IS US/We are still here/Elder and young/Friend and neighbor.” But the book doesn’t end with the poem. Extensive end notes include a recipe and instructions for making fry bread. In an author’s note Kevin Noble Maillard amplifies the history of fry bread — “Many tribes trace the origin of modern Indian cooking to this government-caused deprivation. From federal rations of powered, canned, and other dry, government-issued foods, fry bread was born.” He annotates every spread with more information including the fact that a daily diet of fry bread exacerbates health problems. He compares it to Halloween candy — an infrequent but special treat, but also notes that Native Peoples often don’t have access to “convenient places to buy fruits and vegetables.”

In the note accompanying “FRY BREAD IS COLOR” he reminds us that Native people may have blonde hair or black skin, tight cornrows or a loose braid. This wide variety of faces reflects a history of intermingling between tribes and also with people of European, African, and Asian descent.”

Maillard has said he wrote this book partly so his own children could read about Indigenous People, but it is a gift to all of us. The information in the end papers is so extensive, so well written (and foot-noted!) that it will enrich the mind of every reader. This is a book to savor, to leave in Little Free Libraries, to give to grandchildren, nieces, and nephews.

All of that, plus this book makes us want to make fry bread. “FRY BREAD IS US” reminds us of community and how shared foods and shared meals bind us together. Although this Thanksgiving will be one in which many of us will celebrate in our own homes without extended family to try to stem the spread of the coronavirus, we will find ways to be together — facetiming while cooking, zooming while we eat. Cooking, eating, sharing will still hold us together, even when we are geographically apart.

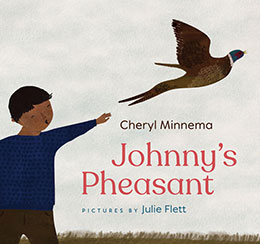

Cheryl Minnema has written another book worthy of any writer’s book envy—Johnny’s Pheasant (illustrated by the wonderful Julie Flett and published by the University of Minnesota Press). Johnny and Grandma are on the way home from the market with “a sack of potatoes, a package of carrots, bundles of fresh fruit and frosted cinnamon rolls” when Johnny notices “a small feathery hump” in the ditch. They stop and it turns out the hump is a sleeping pheasant. Grandma thinks it was hit by a car but would love to have the feathers for her crafts. So they put the pheasant into a bag and the bag into the trunk.

Cheryl Minnema has written another book worthy of any writer’s book envy—Johnny’s Pheasant (illustrated by the wonderful Julie Flett and published by the University of Minnesota Press). Johnny and Grandma are on the way home from the market with “a sack of potatoes, a package of carrots, bundles of fresh fruit and frosted cinnamon rolls” when Johnny notices “a small feathery hump” in the ditch. They stop and it turns out the hump is a sleeping pheasant. Grandma thinks it was hit by a car but would love to have the feathers for her crafts. So they put the pheasant into a bag and the bag into the trunk.

At home, Johnny finds a cardboard box for the pheasant and Grandma agrees that it can stay in the house while he builds a nest of sticks. Johnny is so happy he runs around the yard, “hoot, hoot,” “hoot, hoot.”

As Johnny heads out the door, surprise! The pheasant hoots and flies out of the box, around the room, and lands on Grandma’s head, swaying his tail in front of Grandma’s face. Then it flies out the door. The pheasant lands on top of the swing set briefly and then flies away.

But the story is not over. Johnny finds one pheasant feather at his feet after the pheasant leaves. He runs around the yard with it and eventually gives it to Grandma. “Howah,” says Grandma. Johnny says “hoot, hoot.” We learned from Debbie Reese’s “American Indian Children’s Literature” that “Howah” is an Ojibwe expression meaning “oh my!”

What we love about this story is the affectionate lingering on details. We know exactly what they have bought — and note the poetry, the lovely sounds — “a sack of potatoes, a package of carrots, a bundle of fresh fruit, and frosted cinnamon rolls.”

Some might think a child running around the yard is not enough drama, but they don’t know children, don’t know the power of excitement at having brought home a beautiful bird. They don’t know the joy of one beautiful feather gifted by a bird, and gifted again to a grandma. This book is a wonderful reminder to pay attention to the daily adventures of living in the world. And the joy of being right — the pheasant isn’t dead, as Grandma thinks.

Cheryl Minnema is a member of the Mille Lacs band of Ojibwe. Julie Flett is a Cree-Métis who lives in Canada and whose work we have loved since we first saw it. Her use of white space makes her deep, brilliant colors stand out even more — the red truck Grandma drives and the flowers on her sweater, the orange carrot tops with green frondy leaves in the white grocery bag, the grassy green roadside where they find the pheasant, Grandma’s yellow skirt, Johnny’s dark blue shirt, the turquoise sofa where Grandma sits while playing cards. The ear delights in Minnema’s poetic spare text, and the eye soaks up the illustrations. This book is a feast.

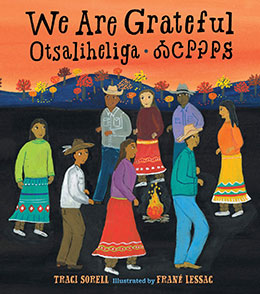

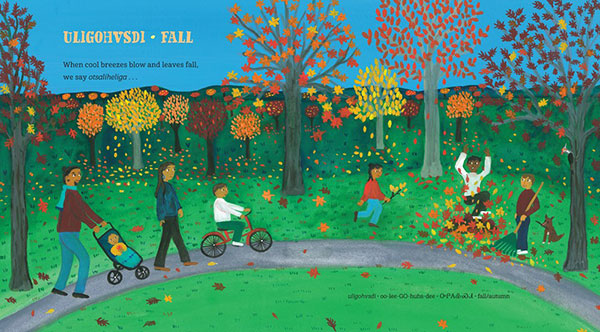

In We Are Grateful by Traci Sorell, an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation, the author explains that in Cherokee culture showing gratitude is part of everyday life throughout the year. In fall, she writes, we are grateful when shell shakers dance in the Great New Moon Ceremony, when we have a feast for the Cherokee new year, collect branches for baskets, and remember the ancestors on the Trail of Tears. In winter, we are grateful for elders sharing stories, bread and soup, traditional crafts and games, for remembering those who have passed on, and for babies cradled in arms. In spring, we are grateful for spring’s first food, for planting strawberries, for an ancestor’s stories, for a relative heading off to serve our country. Summer is the time to be grateful for catching craw dads, for harvest in the green corn ceremony, for listening to tribal leaders speak. Every day, every season, the book concludes, we are grateful. Threaded throughout the book are Cherokee words, and each season contains the Cherokee word for, “we are grateful,” Otsaliheliga.

In We Are Grateful by Traci Sorell, an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation, the author explains that in Cherokee culture showing gratitude is part of everyday life throughout the year. In fall, she writes, we are grateful when shell shakers dance in the Great New Moon Ceremony, when we have a feast for the Cherokee new year, collect branches for baskets, and remember the ancestors on the Trail of Tears. In winter, we are grateful for elders sharing stories, bread and soup, traditional crafts and games, for remembering those who have passed on, and for babies cradled in arms. In spring, we are grateful for spring’s first food, for planting strawberries, for an ancestor’s stories, for a relative heading off to serve our country. Summer is the time to be grateful for catching craw dads, for harvest in the green corn ceremony, for listening to tribal leaders speak. Every day, every season, the book concludes, we are grateful. Threaded throughout the book are Cherokee words, and each season contains the Cherokee word for, “we are grateful,” Otsaliheliga.

We are grateful to have read this book, which reminds us that gratitude is a daily practice, and that we have much to be grateful for, from spring onions to the passing on of culture from one generation to another. And in uncertain times being grateful for the small things can be a calming constant for young and not-so-young.

Like the illustrations in Fry Bread, Frané Lessac’s bright, cheerful, contemporary illustrations show a range of skin tones that reflect the diversity of native people.

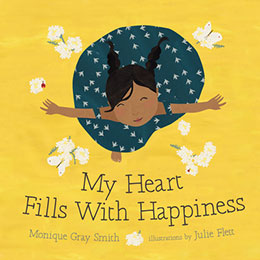

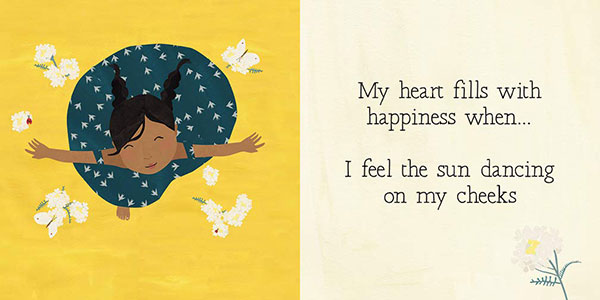

Just looking at the cover of the board book My Heart Fills With Happiness makes us happy — a First Nation child, seen from above, the skirt of her blue dress patterned with white birds swirling as though she is twirling with arms out stretched, her face blissful. White flowers scatter around the yellow background — a bright cheerful and, yes, happy, image. Written by Monique Gray Smith of Cree, Lakota, and Scottish descent and illustrated by Julie Flett, the book celebrates happiness through the senses and connection with others: the smell of bannock baking in the oven, the sun dancing on one’s cheeks, singing, dancing, drumming, walking barefoot on the grass, listening to stories, holding the hand of a loved one. Flett’s art makes these seemingly simple acts luminous.

Just looking at the cover of the board book My Heart Fills With Happiness makes us happy — a First Nation child, seen from above, the skirt of her blue dress patterned with white birds swirling as though she is twirling with arms out stretched, her face blissful. White flowers scatter around the yellow background — a bright cheerful and, yes, happy, image. Written by Monique Gray Smith of Cree, Lakota, and Scottish descent and illustrated by Julie Flett, the book celebrates happiness through the senses and connection with others: the smell of bannock baking in the oven, the sun dancing on one’s cheeks, singing, dancing, drumming, walking barefoot on the grass, listening to stories, holding the hand of a loved one. Flett’s art makes these seemingly simple acts luminous.

The book concludes with an image of the child in a yellow rain slicker perched on an elder’s shoulders, viewing the ocean where narwhals swim. The last line asks, what fills your heart with happiness? It’s a question to give serious consideration: happiness is a form of resistance, and we need to pay attention to what makes us happy.

Monique Gray Smith is a new-to-us author. When we looked at other books she has written, we also fell in love with You Hold Me Up, illustrated by Danielle Daniel. In the same simple, lyrical prose, Smith celebrates the ways in which we hold each other up: when you are kind to me, when you share with me, when we learn together, when you play with me, laugh with me, sing with me, comfort me, listen to me, respect me. The book concludes, “You hold me up. I hold you up. We hold each other up.” In this trying and sometimes terrifying year, we am grateful for all those who help hold us up and who, we hope, we help hold up, too.

Monique Gray Smith is a new-to-us author. When we looked at other books she has written, we also fell in love with You Hold Me Up, illustrated by Danielle Daniel. In the same simple, lyrical prose, Smith celebrates the ways in which we hold each other up: when you are kind to me, when you share with me, when we learn together, when you play with me, laugh with me, sing with me, comfort me, listen to me, respect me. The book concludes, “You hold me up. I hold you up. We hold each other up.” In this trying and sometimes terrifying year, we am grateful for all those who help hold us up and who, we hope, we help hold up, too.

This month’s books help us remember that our strength is in connection and community. And we are grateful.