Jackie: Julius Lester loved language and he loved story.

Phyllis: Language, Lester wrote, is not just words and what they mean; music and rhythm are also part of the meaning. Just reading his books for children makes us want to read them out loud to hear that music and rhythm along with his gift for putting words together.

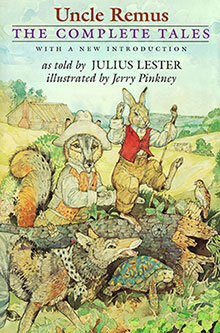

Jackie: He seems to have considered it one of his missions to rescue stories, stories with worn-out stereotyped images, that no longer fit comfortably in our cultural narrative, and shape them into brilliant, humorous, humanistic stories. He re-told the Uncle Remus stories in The Tales of Uncle Remus (1987), illustrated by Jerry Pinkney. He writes in the introduction: “The purpose in my retelling of the Uncle Remus tales is simply: to make the tales accessible again, to be told in the living rooms of condominiums as well as on the front porches of the South.”

Jackie: He seems to have considered it one of his missions to rescue stories, stories with worn-out stereotyped images, that no longer fit comfortably in our cultural narrative, and shape them into brilliant, humorous, humanistic stories. He re-told the Uncle Remus stories in The Tales of Uncle Remus (1987), illustrated by Jerry Pinkney. He writes in the introduction: “The purpose in my retelling of the Uncle Remus tales is simply: to make the tales accessible again, to be told in the living rooms of condominiums as well as on the front porches of the South.”

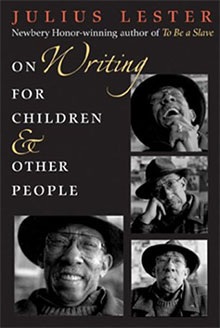

Phyllis: Julius Lester wrote over four dozen books, both fiction and nonfiction, about Black American history — history that bound black lives together “like beads strung on a necklace of pain.” In On Writing for Children and Other People Lester says that stories help us connect with others. “I write because our lives are stories.”

Phyllis: Julius Lester wrote over four dozen books, both fiction and nonfiction, about Black American history — history that bound black lives together “like beads strung on a necklace of pain.” In On Writing for Children and Other People Lester says that stories help us connect with others. “I write because our lives are stories.”

He once wrote, “If enough of these stories are told, then perhaps we will begin to see that our lives are the same story. The differences are merely in the details.” His books include both picture books and longer works.

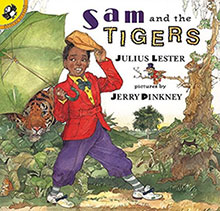

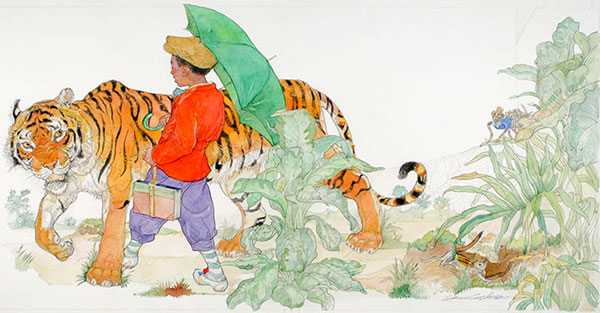

Jackie: One of my all-time favorite of his picture books is another collaboration with Jerry Pinkney, another re-telling, Sam and the Tigers (1996). In an afterward, Julius Lester writes of the original book by Helen Bannerman, “It would be unfair to say Bannerman had a racist intent in creating Little Black Sambo. … Intentionally or not, Little Black Sambo reinforced the idea of white superiority through illustrations exaggerating African physiognomy and a name, Sambo, that had been used negatively for blacks since the early seventeenth century. … Yet the story transcended its stereotypes … There was obviously an abiding truth … I think it is the truth of the imagination, that incredible realm where animals and people lived together like they don’t know any better, and children eat pancakes cooked in the butter of melted tigers, and parents never say, ‘Don’t eat so many.’”

Jackie: One of my all-time favorite of his picture books is another collaboration with Jerry Pinkney, another re-telling, Sam and the Tigers (1996). In an afterward, Julius Lester writes of the original book by Helen Bannerman, “It would be unfair to say Bannerman had a racist intent in creating Little Black Sambo. … Intentionally or not, Little Black Sambo reinforced the idea of white superiority through illustrations exaggerating African physiognomy and a name, Sambo, that had been used negatively for blacks since the early seventeenth century. … Yet the story transcended its stereotypes … There was obviously an abiding truth … I think it is the truth of the imagination, that incredible realm where animals and people lived together like they don’t know any better, and children eat pancakes cooked in the butter of melted tigers, and parents never say, ‘Don’t eat so many.’”

In their re-telling, Lester and Pinkney aim directly for the truth of the imagination. Sam lives in the town of Sam-sam-sa-mara where everyone is named Sam. Sam, his mother, and his father all are named Sam. “Nobody was named Joleen or Natisha or Willie…. One day Sam and Sam and Sam went to the market place to get some new clothes for school.” They started out at Mr. Elephant’s Elegant Habilments. Sam insisted to his parents that he be allowed to pick out his own clothes. “Sam looked at Sam. Sam shrugged. Sam shrugged back. Sam nodded. Sam nodded back. Sam and Sam looked at Sam and nodded together. Sam grinned.” I am grinning, too, as I read this sentence to myself. What fun!

Over the course of the shopping trip Sam picks out a coat as “red as a happy heart,” pants as “purple as a love that would last forever,” a shirt “as yellow as tomorrow,” silver shoes “shining like promises that are always kept,” and an umbrella “as green as a satisfied mind.” The sounds of the words and the similes are so satisfying I could go shopping with Julius Lester and Sam all day long.

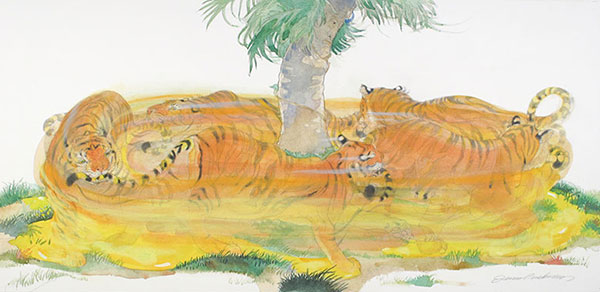

Of course we know what happens with the tigers. (And Jerry Pinkney’s tigers threaten to jump off the page and demand my sweater, soft as a song of forgiveness and grace.)

The tigers grab each other by the tail and run “Faster and faster and faster and faster…until — they melted into a pool of butter as golden as a dream come true.” When Sam gets home his mother makes pancakes for the neighborhood. The talk is of five tigers who have disappeared. And the pancakes, orange and black-striped, are delicious — butter‑y. Sam ate a hundred and sixty-nine. “Wearing all them colors can really make a boy hungry.”

This is a story to drop into little free libraries all over town, to read with kids of all ages, to read before and after pancakes. Thanks to Julius Lester and Jerry Pinkney for giving it back to us.

After they collaborated on Sam and the Tigers, this same duo wrote and illustrated Black Cowboy, Wild Horses, a true story of Bob Lemmons. Lemmons, a former slave, “could look at the ground and read what animals had walked on it, their size and weight, when they had passed by, and where they were going.” He is looking to bring in a band of mustangs, by himself. “No one he knew could bring in mustangs by themselves, but Bob could make horses think he was one of them — because he was.”

After they collaborated on Sam and the Tigers, this same duo wrote and illustrated Black Cowboy, Wild Horses, a true story of Bob Lemmons. Lemmons, a former slave, “could look at the ground and read what animals had walked on it, their size and weight, when they had passed by, and where they were going.” He is looking to bring in a band of mustangs, by himself. “No one he knew could bring in mustangs by themselves, but Bob could make horses think he was one of them — because he was.”

This is not just a story of a cowboy and mustangs, it’s also Pinkney’s wonderful paintings and Lester’s satisfying similes. Though published in 1998 it is so fresh and dramatic it could have been published yesterday.

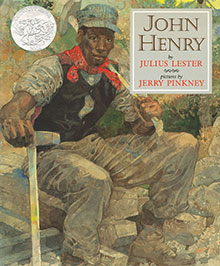

Phyllis: Pinkney and Lester also gave us the Caldecott Honor Book John Henry, (1994). Though it is so much more, the book starts like a tall tale. Almost as soon as John Henry was born “he grew so big he broke through the porch roof.” The next day he rebuilt the porch, adding “one of them jacutzis” for his parents. Soon after he decided to go on the road with his daddy’s gift of “two twenty-pound sledgehammers with four-foot handles made of whale bone.” When he met a road crew stymied by a huge boulder even dynamite wouldn’t touch, John Henry swung his two hammers so hard a rainbow settled around his shoulders. John Henry beat the boulder into “the prettiest and straightest road,” then headed off to find work on the crew building the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, which had encountered a mountain so big it made even John Henry feel small.

Phyllis: Pinkney and Lester also gave us the Caldecott Honor Book John Henry, (1994). Though it is so much more, the book starts like a tall tale. Almost as soon as John Henry was born “he grew so big he broke through the porch roof.” The next day he rebuilt the porch, adding “one of them jacutzis” for his parents. Soon after he decided to go on the road with his daddy’s gift of “two twenty-pound sledgehammers with four-foot handles made of whale bone.” When he met a road crew stymied by a huge boulder even dynamite wouldn’t touch, John Henry swung his two hammers so hard a rainbow settled around his shoulders. John Henry beat the boulder into “the prettiest and straightest road,” then headed off to find work on the crew building the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, which had encountered a mountain so big it made even John Henry feel small.

When John Henry heard that a steam engine said to out-hammer ten men was being brought in to drill through that mountain, he challenged the steam drill to see who could tunnel the farthest through the mountain. Swinging his two twenty-pound hammers with “muscles hard as wisdom” John Henry beat the steam drill by a mile.

As he walked out of the tunnel to cheering folks, though, John Henry fell dead. “He had hammered so hard and so fast and so long that his big heart had burst.” Folks swore they heard the rainbow whisper, “Dying ain’t important. Everybody does that. What matters is how well you do your living.”

Julius Lester wrote that when he was asked to write about John Henry, he talked to Jerry Pinkney, who had researched the story to illustrate it, and asked him what he saw in John Henry As they talked, wrote Lester, “the image of Martin Luther King, Jr., came to me … I suspect it is the connection all of us feel to both figures — namely, to have the courage to hammer until our hearts break and to try to leave our mourners smiling in their tears.”

Tuesday, April 20, 2021, almost a year after the murder of George Floyd, a jury found the police officer, who knelt on Floyd’s neck until he died, guilty on all three charges. In the people who bore witness, the people who testified, the jury who decided, the countless many who have worked and marched and protested for accountability and justice with boots on the ground, that same spirit — courage as hard as wisdom — lives on.

and E 38th St in Minneapolis, Minnesota CC BY-SA 2.0

Outstanding article. Glad to see that you continue to write for Bookology. So much solid thinking goes into this publication. So many resources. Takes me away from TV and newspaper, etc.