Libraries hold countless books of knowledge, wisdom, imagination, possibilities. They are places with access to technology for anyone with a library card, places for tutoring students, places for story time. We want to look at books about these magical places, portals to our world, our selves, and other worlds and selves we might become. We have stories of the magic of libraries and the passion of those who build libraries and share them with readers.

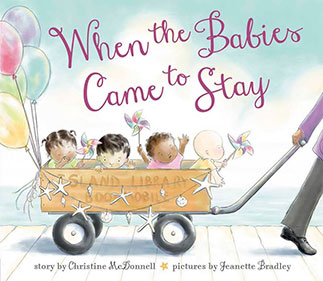

In When the Babies Came to Stay written by Christine McDonnell and illustrated by Jeanette Bradley, four babies mysteriously arrive on a small island with notes asking for shelter, safety, and loving care. The island librarian takes them home to raise in — where else? — the library where she lives in the attic. She names them Agatha, Brian, Charles, and Dorothy, all with her last name of Book.

The islanders pitch in, making cribs from lobster traps, coverlets from sails, teaching the Books sea chanties, fishing, how to recognize birds, (and of course, how to read) because “the babies belonged to the island.” We see the babies growing in Jeanette Bradley’s softly colored illustrations with plenty of white space that evokes the open sky above the sea.

When other island children ask why the Books don’t look alike and why they live at the library, the librarian explains that some questions don’t have answers but that their parents sent them with love to a place where they would be safe and that “where we’re going is more important than where we came from.”

The story ends:

“A, B, C, D, and E [the librarian Eleanor] were a set of Books.

The library was where they lived,

and the island was where they belonged.”

Who wouldn’t want to live in an island library, cared for and raised by folks who love them?

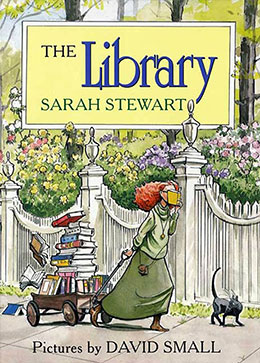

Libraries have to come from somewhere. And we want to include a couple of books about collecting books. The Library (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), by Sarah Stewart and illustrated by David Small is first about a reader. It’s a classic, published in 1995, and named by the New York Times as one of the best books of that year. The book is dedicated to “To the memory of the real Mary Elizabeth Brown, Librarian, Reader, Friend 1920 – 1992.”

The real Mary Elizabeth Brown inspired a charming “tallish” tale, about a person who loves to read and always has. As a child she manufactured library cards and loaned books to her friends. She shares with the Babies the fact of mysterious origin, she “dropped straight down from the sky.”

As an adult she only cares about books, acquires more and more until her house cannot hold another. Then Elizabeth Brown marches to the town courthouse where she signs over all her possessions. Her house becomes the Elizabeth Brown Free Library, and she moves in with a friend, who makes regular visits to the library with her.

This book is written in a lilting rhyme that makes it fun to read, fun to hear. And David Small’s illustrations invite us to spend extra time with each spread.

We writers love stories about people who do just what they want, especially when what they want is to buy books and read.

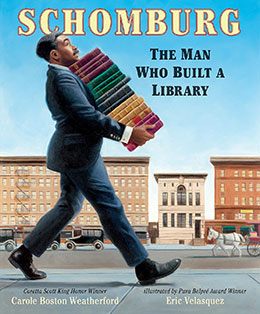

Elizabeth Brown started a library. We aren’t told what books she bought. Carole Boston Weatherford has told a story of another person who started a library, amassed a collection and gave it away — Arturo Schomburg — in the book Schomburg The Man Who Built a Library, illustrated by Eric Velasquez (Candlewick, 2017).

In a series of prose poems Weatherford tells the story of a man born in Puerto Rico in 1874. When Arturo was in fifth grade he was told by a teacher that “Africa’s sons and daughters had no history, no heroes.” That rankled the boy and at some point he realized that could not be true. In 1891 he emigrated to New York City. In a poem titled “Book Hunting Bug,” Weatherford tells of Schomburg’s early efforts to locate stories of African Americans. He found a book of poems by Phillis Wheatley, books by Frederick Douglass, writings about the Haitian Revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture.

Weatherford writes Schomburg, “chased the truth and turned up icons whose African American heritage had been whitewashed.” For example, few knew that John James Audubon had been the son of a French plantation owner and a Creole chambermaid. And the African heritage of others had also been erased: Pushkin’s great grandfather had been kidnapped from Central Africa; Alexander Dumas was a descendant of slaves; Beethoven’s mother was said to be a Moor.

In pursuing his life’s work,this mailroom clerk supported Marcus Garvey’s newspaper and corresponded with Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois.

He loaned his books to students, artists, and writers and served on a committee formed to start a Negro branch of the New York Public Library. As he acquired more and more books his house filled up. There were even books in the bathroom. Eventually the Carnegie Corporation bought his entire collection — more than 5000 books, several thousand pamphlets and priceless prints and papers. Weatherford quotes Schomburg, “I am proud to be able to do something that may mean inspiration for the youth of my race.”

This beautiful book is for readers old enough to wonder about other lives. And it has a dual purpose. It tells of the remarkable life and accomplishments of Arturo Schomburg. And it tells of the remarkable lives he learned about in pursuing his passion.

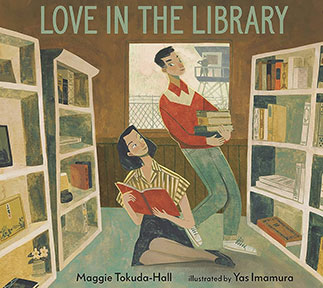

Love in the Library by Maggie Tokuda-Hall, illustrated by Yas Imamura, is set in Minidoka, a World War II internment camp surrounded by barbed wire, guard towers, and desert where people are imprisoned simply for being Japanese American. Tama, one of the prisoners, works in the library. George, another prisoner, waits at the door every day to return yesterday’s stack of books and check out more books.

When the library is quiet, Tama escapes into books. “Pressed between their covers were words that planted seeds in the garden of Tama’s mind. How magical that — even in Minidoka — such a small little library could fit so much inside of its four walls!”

When Tama asks George how he can read all the books he checks out each day, she realizes he doesn’t just come for the books but to see “what he held close to his heart … Tama.” Eventually, imprisoned in “a place built to make people feel like they weren’t human,” they marry and have a baby. The story ends with a line from the journal that Tama (the author’s grandmother) kept in the camp: “The miracle is in all of us. As long as we believe in change, in beauty, in hope.”

The Librarian of Basra by Jeanette Winter, illustrated in bold colors by the author, begins with a quote by Alia Muhammed Baker, the real librarian of Basra in this true story: “In the Koran, the first thing God said to Muhammed was ‘Read.”’

Alia’s library in Basra, Iraq, is “a meeting place for all who love books.” War threatens, and Alia worries that the library and its books, “more precious to her than mountains of gold,” will be destroyed. When the governor refuses her permission to move them, she secretly carries books home every night to keep them safe.

War does come, and Alia enlists her friend Anis who owns a restaurant next to the library to help her save the books. Alia, Anis, his brothers, and other shopkeepers and neighbors work all night to pass the books over the wall and hide them in Anis’s restaurant. Nine days later the library burns to the ground. When “the beast of war” finally moves on, Alia hires a truck to bring all thirty thousand books to fill up her house and friends’ houses. Then she waits for the war to end, for peace to come, for a new library to be built. “But until then, the books are safe — safe with the librarian of Basra.” We can be grateful for Alia’s courage and determination, and the courage of all librarians who protect their precious treasures for now and for the future.

What to do in the hills of Appalachia where there is no library? Load the books into a bag, jump on a horse and go to readers. There’s courage in that, too. That Book Woman (Atheneum, 2008) by Heather Henson and illustrated by the fabulous David Small is a fictionalized telling of the pack horse librarians of the Appalachians. Cal, the young narrator, says “I am no scholar boy,” and cares nothing for reading. But his sister Lark thinks the book woman is bringing treasures. She comes every two weeks no matter the weather, except for deep winter. In the long cold days Cal gets curious about books and asks Lark to teach him to read. When the Book Woman comes again Cal can read to her.

David Small’s glorious sky on the last spread, a sky that opens before two readers sitting on a porch, makes a beautiful statement about the gifts of books and of reading.

Libraries as homes, as shelter, as places of refuge, places to learn, and places to delight. Where would we be without libraries? Let’s hope we never have to find out.

A few other library books:

Dreamers by Yuyi Morales

A Library by Nikki Giovanni

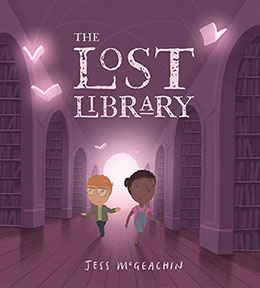

The Lost Library by Jess McGeachin