Poet Lucille Clifton in a 1998 interview “Doing What You Will Do,” published in Sleeping with One Eye Open: Women Writers and the Art of Survival, said, “I think the oral tradition is the one which is most interesting to me and the voice in which I like to speak.” Asked about the most important aspect of her craft, she answered, “For me, sound … sound, the music of a poem, the feeling are most important. I can feel what I can hear.”

Clifton was a poet, but as any writer or reader or hearer of picture books knows, picture books and poetry are kin. Both are meant to be read out loud, savored by the ear and by the tongue. Both depend on sound, on image, on emotion. Every word matters in a poem and in a picture book. So is it any wonder that Lucille Clifton, amazing poet, was also a consummate picture book writer?

Clifton’s stories honor both the everyday lives and also the emotional lives of children. Eight of her picture books are about Everett Anderson, a fictional African-American boy with a single mother who lives in a city apartment, a boy so real to readers that children wrote him letters. Some of the Days of Everett Anderson introduces us to Everett Anderson and takes us through his week, with themes of missing daddy, of mama needing to work, of a boy who realizes being afraid of the dark would mean being afraid of the people he loves and even afraid of himself.

Everett Anderson’s Christmas Coming joyfully celebrates a city Christmas through the days of expectation and excitement for a boy who lives “In 14A … between the snow that falls on downer lives.” He thinks about what he would want if his Daddy was here, and how he should try harder to be good, and how boys with lots of presents have to spend the whole Christmas day opening them and never have fun. When a tree blooms with color in his apartment, and Everett, we see from the art, gets a drum for Christmas, Everett Anderson sees how “our Christmas bounces off the sky and shines on all the downer ones.”

Everett’s Anderson’s Year takes Everett Anderson from January when his Mama tells him to walk tall in the world through the months and events of Everett’s Anderson’s year: waiting for Mama to come home from work, wanting to make America a birthday cake except the sugar is almost gone and he will have to wait until payday to buy more, missing his Daddy wherever he is, not understanding why he has to go back to school again, and realizing, at the end of the year

“It’s just about love,”

his Mama smiles.

“It’s all about Love and

you know about that.”

With Everett Anderson’s Friend his world expands. A new neighbor in 13A turns out to be a girl who can outrun and outplay Everett at ball, and he isn’t interested in being friends. Then one day he locks himself out of his apartment, and Maria invites him in to 13A where her mother “makes little pies called Tacos, calls little boys Muchachos, and likes to thank the Dios.” Everett realizes he and Maria can be friends even if she wins at ball. “And the friends we find are full of surprises Everett Anderson realizes.” A subtle thread throughout the story is Everett Anderson missing his father, who if he were there when Everett locks himself out, would make peanut butter and jelly for him and not be mad at all. We don’t know where Everett’s daddy is, but we feel his yearning for his father even as Everett discovers a new friend.

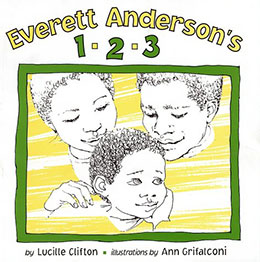

His world expands again in Everett Anderson’s 1−2−3 when Everett Anderson’s mama and a new neighbor, Mr. Perry, hit it off. One can be fun, Everett thinks, but one can be lonely if Mama is busy talking with the new neighbor. Everett likes just the two of them, he and Mama. Mama tells Everett that while she misses his daddy two can be lonely – and things do go on. Everett thinks he can get used to being three, but the story refuses a pat solution.

One can be lonely and One can be fun, and

Two can be awful or perfect for some, and

Three can be crowded or can be just right or

Even too many, you have to decide.

Mr. Perry and Everett Anderson too

Know the number you need

Is the number for you.

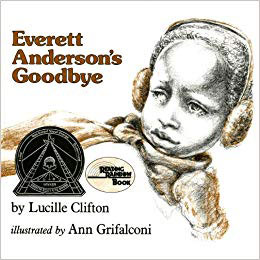

In Everett Anderson’s Goodbye we learn that Everett’s father has died. The spare and tender story takes Everett through the five stages of grief listed at the beginning of the book: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and, after a while, acceptance. In the beginning Everett Anderson holds his mama’s hand and dreams of “just Daddy, Daddy forever and ever.” An angry Everett declares he doesn’t love anybody, or anything, and a bargaining Everett promises to learn his nine times nine and never sleep late or gobble his bread if Daddy can be alive again. Everett can’t even sleep because “the hurt is too deep.” After some time passes Everett comes to acceptance of his daddy’s death and says, “I knew my daddy loved me through and through, and whatever happens when people die, love doesn’t stop, and neither will I.”

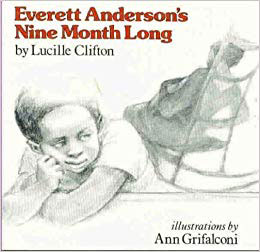

The library’s copy of Everett Anderson’s Nine Month Long has a splendid surprise on the title page: Lucille Clifton’s signature and the inscription, For Ian — Joy! 2⁄81. The story tells about Everett dealing with a coming new baby in the family and tenderly shows his feelings, from anticipation to feeling left out. Mr. Perry, who is now Everett’s stepfather, helps Everett know that his mama

… is still the same

Mama who loves you whatever her name

and whatever other sister or brother

you know you are her

special one,

her firstborn Everett Anderson.

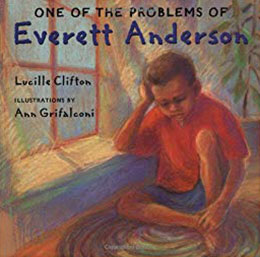

Over the course of these stories Everett Anderson grows in empathy and understanding. In the last book One of the Problems of Everett Anderson he worries about what to do when a friend shows up every day “with a scar or a bruise or a mark on his leg” and has the “saddest saddest face like he was lost in the loneliest place.” When Everett tells Mama he doesn’t know how to help his friend Greg, she listens and hugs him hard and holds his hand.

and Everett tries to understand

that one of the things he can do right now

is listen to Greg and hug and hold

his friend, and now that Mama is told,

something will happen for Greg that is new.

Sometimes the little things that you do

make a difference.

Everett Anderson hopes that’s true.

Clifton’s stories recognize that not all problems are easily solved, but in the delicate strength of this telling, Everett learns that doing little things might make a difference for his friend. We hope so, too.

From 1970 until her death in 2010 Lucille Clifton made poetry of everyday lives and hearts. Read some of the books of Lucille Clifton. Read them all.

They’re all about love, and we know about that.

P.S. Another month we want to share some of the other wonderful children’s books by Lucille Clifton.

This is wonderful – thanks for writing it! I know far less about Lucille Clifton’s children’s books than I do about her poetry collections – one of which, Blessing the Boats, is right here on my desk. Clifton signed it when she came to Bryn Mawr College to do a reading in 2007.… one of the most memorable readings I’ve ever attended. Her voice is so strong and it lives on and on!

While working on this column we both ordered Blessing the Boats to hear more about her amazing voice and words. How wonderful to have heard her in person!