As we enter the dark time of year and who knows what other kinds of dark times we may be facing, we are looking for stories of hope — and finding them.

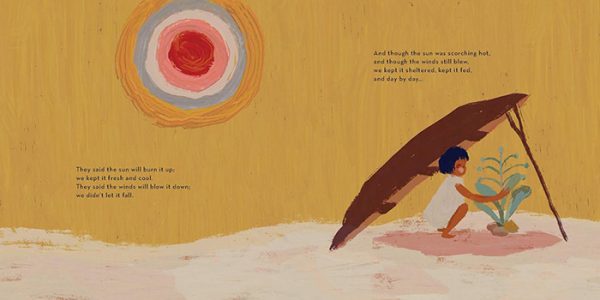

Maybe You Might, written by Imogen Foxell and illustrated by Anna Cunha, reminds us all that even the smallest acts can make a difference. It begins: “They said I couldn’t change the world:/it wasn’t worth the fight. /But in my head, a small voice said…/…maybe you might.” So our narrator plants a single seed in “the very hottest, driest place/on all this hot, dry earth.” We learn that the river has dried up, the grass turned to desert, “The land was bare beyond repair, / at least until the day…/…I found a seed.”

She brings water every day to the little seed in the ground by the “long dead riverbed” and protects the sprouting seedling from the scorching sun and drying wind. A tree grows, puts up leaves, and fruits. From the fruits they plant more seeds. The tree roots find water deep in the ground. “The water rose up high. /It reached the leaves, it turned to steam,/and build clouds in the sky./ The clouds were full of water./The water turned to rain./ Until one day our country had…/…a river once again!” The forest thrives and birds, animals, and bees return.

Through the art, done in rich, earthy colors, we see the child narrator grow up and have a child of her own. When a storm takes down the original tree, a child (perhaps the narrator’s own) offers the now-grown narrator a seed to plant. In the last spread we see the narrator as a white-haired elder in the midst of the reawakened land with her now-grown child carrying a child of her own.

published by Lantana Publishing, 2022

The book ends with an exhortation: “They say that you can’t change the world, /that it’s not worth the fight. /But help things grow, you never know…/…maybe you might.” What kinds of seeds might we plant? Let’s keep our eyes out.

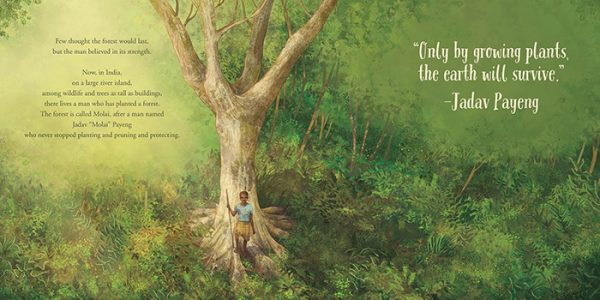

And what is more hopeful than planting trees? In the true story of The Boy Who Grew a Forest by Sophia Gholz and illustrated by Kayla Harren, Jadav Payeng plants trees on a river island in India. As a child he witnessed the death of animals as the flooding river washed away their homes, and he worried that the island might become uninhabitable for animals and people.

When he told the village elders of his worries they gifted him with twenty bamboo saplings. He planted the saplings on a large sandbar, “…too barren for animals, /the shores too sandy for leafy trees.” He built a watering system to water the trees and lugged buckets of water from the river. And the bamboos grew.

Then he realized he would have to create richer soil for more trees. “The boy carried cow dung, earthworms, termites and angry red ants that bit him on the journey to their hew home. “ He brought more seeds and planted more trees. As he grows, he continues to plant more trees. The little patch of bamboo shoots grows to forty acres. Wildlife returns. Harren’s illustrations show us rhinos, herons, water buffalo, elephants, gibbons, and all kinds of birds — even tigers. He planted grasses to attract small animals so hungry tigers would not raid the villages, fruit trees to feed the hungry elephants.

published by Sleeping Bear Press, 2019

Now the forest is call “Molai”, named for the man “who never stopped planting and pruning and protecting.” An author’s note tells us that the Molai forest is now 1,300 acres and home to “thousands of different species of plants and trees…” and “provides life and shelter for many animals, some endangered.” One person devoting a lifetime to change is a cause for hope. Many people devoting some time to make change could also be a cause for hope.

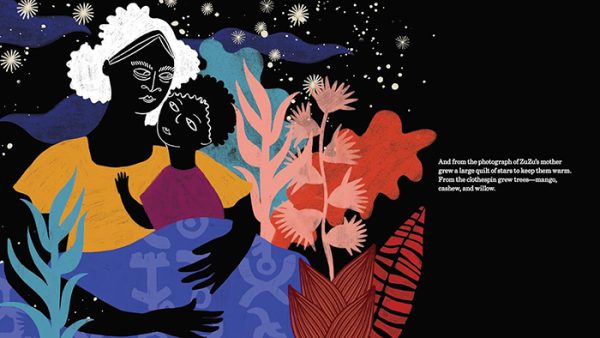

Stories of resilience are also stories of hope. Kamau & Zuzu Find a Way, written by Aracelis Girmay and illustrated by Diana Ejaita, is an unforgettable story that begins: “Nobody knows how it happened. / Mama ZuZu woke up one morning, /and she and her grandchild were on the moon. / ‘I must have fallen asleep because I woke up/right here in my chair, a book at my feet,/and you warm against my belly.’”

Though ZuZu misses her home she knows she must make a new home out of this new place. She touches the ground. “’Hello there, Sister,’ she said.” She, too, plants seeds. “First she planted a kernel of corn and a clothespin that was still in her apron. Another, day she planted the photograph of her mother and a square of cloth that she always kept tucked inside her book.”

The moon crust helps these seeds to grow: moon corn, moon beans. “From the photograph of ZuZu’s mother grew a large quilt of stars to keep them warm. From the clothespin grew trees — mango, cashew, and willow. And from the square of cloth, a wide and silent kite.” When ZuZu cries from longing for her home her tears create a deep well of water.

Back home Kamau’s parents search everywhere for the child and grandma, “for days, then weeks, then years.” One day a letter settles on Kamau’s father’s shoulders. “It began: Hello?! Anybody out there?!/I am with Mama ZuZu on the moon.” The parents are so excited they run to tell their children, and other family members. “They shouted to anyone who would listen — the cat, the plants, even the teakettle. ‘They are all right! They have sent word!’” Everyone rejoices, but no one knows how to write back until Kamau’s sister writes a letter into the sand and lets the sea take it away. After that, letters travel back and forth, carried by the sea and written in moon dust. “This is not what I would have chosen. ZuZu sometimes thought to herself, raising a boy so far away from family. None of the roads Back Home lead here.

‘But we will have to find a way to live, as people do.”’

published by Enchanted Lion, 2024

The art, which School Library Journal calls “gorgeous and evocative,” is done in vibrant colors and patterns against the deep black of space. Described as a modern folktale about African diaspora, this beautiful story is both heartbreaking and hopeful. We will all find a way to live, live with joy, and make our own change, as people do.

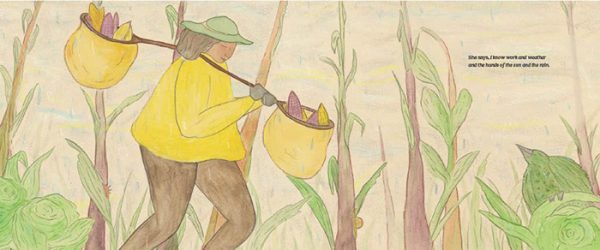

What Do You Know? reminds us of the deep wisdom of love all around us. Throughout the book love asks, What do you know? Spread by spread, we learn the answers. The well says, “I know thirst, I know abundance. I know depth, I know darkness.” Farmers reply that they know “the colors of earth’s flat face… work and weather and the hands of the sun and the rain.” Honeybees know the flowers, the “hexagon and the color gold” of honey, and the hungry black bear.

The rock replies to love, “I know the force of the water and the force of the wind. And I know that change is possible, even if it takes a million years.” Even the goats and bats answer love, naming what they know. Courage knows “speaking, even though I am afraid…and the daily work of keeping on.” When love comes to the land and asks what it knows, the lands says, “I know the joy of going on and on and on. I know the laughter of children who run below the birds, and the heels and toes of the elders who planted the seeds. I know the ancestors and their ancestor dreams, the hoping song that is brown and the hoping song that is green.”

It’s hard to resist simply quoting the whole book for the answers to love’s question, what do you know? The poetry of the language is matched by the art, done in colored pencil and watercolor, which flows across the spreads. The stars, when they answer, visually gleam on the page against the “vastness of the deep, dark night.”

published by Enchanted Lion, 2019

What Do You Know? is a collaboration between Aracelis Girmay, (who also wrote Kamau and Zuzu Find a Way) and her sister Ariana Fields. In an author’s note they explain that they wanted to make something to give very young people “a refuge, an encouragement, an insistence on wonder and wonder anywhere.”

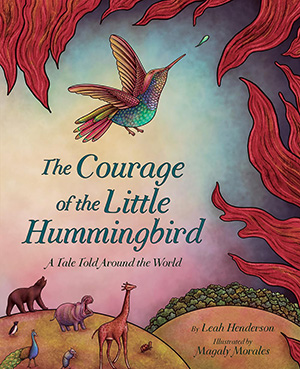

The Courage of the Little Hummingbird, by Leah Henderson, gloriously illustrated by Magaly Morales, is a tale told round the world in ” whispers, in shouts, and in many different languages.… ” And like tales everywhere, it begins, “Long, long ago…”

When fire breaks out in the Great Forest, the animals — a troop of baboons, a shadow of jaguars, a roll of armadillos, a nest of snakes, a bed of sloths, a litter of rabbits, and a pandemonium of parrots — all flee across the river to escape.

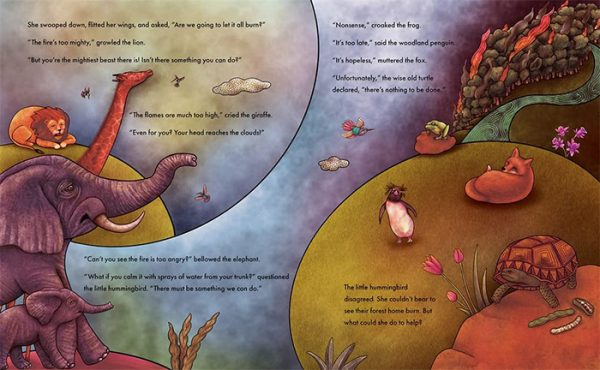

The little humming bird can’t bear to abandon the forest that had protected and fed her, but when she asks the other animals to do something, they respond that the fire is too mighty, too high, too angry — that it’s too hopeless to fight it.

The little hummingbird flies up, dives down, and skims the river, filling her beak with water and flying toward the flames. The other animals urge her back, but she releases a single drop of water onto the fire. Again and again she flies with a tiny beak full of water and drops it on the fire. “One drop./Then another./Then one drop more.”

When the other animals shout, “What do you think you’re doing?” the hummingbird replies, “I’m doing all I can.” The other animals hush, then gather at the river’s edge. “Ready to do all they can to save their forest home. Together.”

written by Leah Henderson, published by Harry N. Abrams, 2023

An author’s note explains how versions of this story are told around the globe and that Wangari Maathai first heard it on a trip to Japan. Maathai often said, “I will be a hummingbird; I will do the best I can.” She began planting trees in her homeland of Kenya and started the Green Belt Movement which eventually planted more than 51 million trees. Henderson tells us that with “one tree, one step, one breath, one word after another,” we can all be like the little hummingbird and do whatever we are able.

Emily Dickinson wrote, “Hope is the thing with feathers.” Hope is also a seed tenderly planted in the ground. A tree growing from a clothespin. Twenty bamboo saplings becoming a mighty forest. A hummingbird fighting a ferocious forest fire. Hope is what you answer with when love comes to you and asks, “What do you know?”

And hope is the authors and illustrators of children’s books like these that remind us of strength and of wonder and of finding a way. As people do.